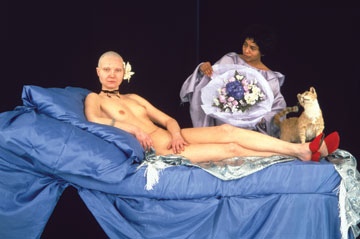

Katarzyna Kozyra, "Olimpia," detail, 1996. Deposit of the National Museum in Cracow. Courtesy Zachęta National Gallery of Art.

At the turn of December and January, the myriad summaries and best-of lists of the past year I browse through coincide with a more personal check-up. There is no better way to evade lengthy and lethally sweet Polish family reunions than a quick run-through the Warsaw museum and gallery scene. This annual timing, regulated by the holiday season, allows both distance and regularity.

The must see item for the last chock-full of activity visit was the monographic exhibition of Katarzyna Kozyra at Zachęta National Gallery of Art, which summarizes both 20 years of the artist’s career and, simultaneously, is the implicit survey of the dramatic transformation of the Polish art scene. When Kozyra debuted in 1993 with her Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts‘ diploma work Pyramid of Animals, she stirred a public outcry and a debate that continued well into the 2000s. She became the synonym of “a critical artist” and her work became the flag post of the period called “the cold war between art and society,”a term coined by another contemporary maker under constant media scrutiny, Zbigniew Libera. If, at the end of the decade, Poland has finally entered a period of artistic normalization, as some critics recently celebrated, at a loss is the sense of urgency expressed over the implications of Kozyra’s work (notably, it would be hard to speak of its opponents and sympathizers today).

Katarzyna Kozyra, "Pyramid of Animals," installation, 1993. Courtesy: Zachęta National Gallery of Art.

Ironically, Pyramid of Animals had its uncanny doppelganger in the work of Maurizio Cattelan, Love Saves Life (1995), perhaps proving that in addition to Arthur Danto’s “Historical Museum of Monochrome Art,” we could also construct a museum of shockingly-similar anti-modernist sculpture. Both pieces consist of four taxidermic animals standing on top of each other, loosely reflecting the protagonists of a fairytale by the Brothers Grimm, The Bremen Town Musicians: a rooster, a cat, a dog, and a donkey – more faithful to the Cattelan story would have been a horse – in the case of Kozyra (one of the main criteria for the sculpture was to obtain red-haired animals in order to match the color of the artist’s own hair). Yet, while Cattelan’s piece at best caused some minor discomfort and anxiety – viewers not being sure whether they are dealing with a tricky joke or something truly morbid (you can read about this in Cattelan’s interview with Nancy Spector in the book: Maurizio Cattelan, London: Phaidon, 2000, p. 23–30), after the public presentation of Kozyra’s piece at the Centre for Contemporary Art in Warsaw, all hell broke loose.

Maurizio Cattelan, “Love Saves Life,” 1995. Stuffed animals, 190.5 x 120.5 x 59.5 cm. Collezione Leggeri, Bergamo. Courtesy: https://truffeinrete.blogspot.com, photo: Roberto Marossi.

It would be easy to contribute the media storm that followed solely to the conservatism and traditionalism of Polish society, but there is an important difference between Cattelan’s and Kozyra’s pieces, which might suggest the issue was far more complex. Kozyra accompanied her reticent piece with a short text and a documentary video, which unequivocally implicated her as an individual responsible for the selection of the animals to be stuffed and a direct participant in the killing of the horse and preparation of its carcass. This Barthesian gesture of fixing the meaning of an image with words had grave repercussions: it made the artist the target of countless accusations and attacks. Verbal statements, together with the filming of the process of the piece’s “creation,” had extended the work beyond the sphere of its re/presentation into a complex, social realm of its own making, in which the criteria of judgment and consequences of Kozyra’s actions were far more complex and ambiguous than the standards of evaluation applied to the work sealed off within the proverbial hermetic “white cube.” As Kozyra herself remarked, “[conscious] taking of an animal’s life, performed in a transparent manner and by an individual, ended up a reason for outrage and stigmatization.” (Kozyra in the letter to the editor of the daily Gazeta Wyborcza, August 20, 1993. The excerpt comes from the press materials of Zachęta National Gallery of Art; translation from Polish is mine.)

Katarzyna Kozyra, "Pyramid of Animals," video still from the installation, 1993. Courtesy: Zachęta National Gallery of Art.

Am I mourning the end of the scandal when I say that Kozyra’s work does not stir the same contradictory emotions today? Certainly, the view of members of parliament relieving Pope John Paul II of the burden of a meteorite was equally entertaining as it was tragic and embarrassing. (I am referring here to the infamous 2001 incident in which conservative members of the Polish parliament vandalized another sculpture of Maurizio Cattelan, La Nona Ora — exhibited, coincidentally, also in Zachęta. The discussion over the meaning of the piece led to the resignation of the prominent art historian and director of the institution, Anda Rottenberg.) Yet, what I am really perplexed by is how recent, cooler readings of Kozyra’s work can detach her from the realities of her social background. So for me, to write about her projects at this moment, when they have claimed their place in the Polish (and perhaps also international) canon, is to disagree with the notion that “above all, her work is speaking about her own self, it is performing very painful – at times – self-dissection, it is speaking in the first person singular.” (The statement by Piotr Kosiewski in “Słaby? Dobry? Przeciętny?” [Weak? Good? Average?], one of the articles evaluating year 2010 in Polish art published in the magazine Obieg [translation from Polish is mine].)

Surely, almost without exception (Rite of Spring), Kozyra has systematically inserted her own body into her photo- and video-installation projects. From the 1995 Olimpia, through the late 1990s The [Female] Bathhouse and Men’s Bathhouse (awarded honorable mention at the 1999 Venice Biennale), to the recent Cheerleader and the extensive series of filmed performances In Art Dreams Come True, the artist acts as the main protagonist that consistently confronts the viewers: with the revolting physicality of her imperfect/sick body, with the conspicuous malleability of its sexual appeal, and finally, with the ambiguity and the porosity of its gender. It is worth remembering, however, that these three traits are not exclusively her own and that the manipulations the artist undertakes could be very effectively applied to any body. To see the image of Kozyra in her own work only as a self-reflexive device suggests sealing her off (her many selves contained in her frail body) within the realm of representation. Yet, neither do Kozyra’s games simply deconstruct traditional hierarchies of the sexes, so painfully and deeply rooted in Western and, especially, Polish Catholic culture. Such perspective also short-circuits the potency of the work, narrowing it down to an intervention in the sphere of stable, established symbols; after all, Kozyra is not exactly an essentialist feminist.

As I write this, I have a nervous feeling that Kozyra’s tapping into gender issues has been recently too often seen just as the thing a contemporary artist is supposed to do (and something that provides visibility on the international scene, being “modern” enough for the international circuits) rather than as an action that intervenes in the ailments of a collective body. There is something paradoxical about the celebrations of the artist’s successes without an explicit mention that despite of all the gender-bending interventions in art, an average woman in Poland still cannot get a legal abortion, is required to pay for a costly, private OB-GYN visit four times a year to obtain oral contraceptives and, anyone single after 30 is considered a social freak. Kozyra’s role-playing stems from the same social body, and it is not coincidental that following the reception of the piece Punishment and Crime (2002), the artist felt so uncomfortable in Warsaw that she moved to Berlin.

Kozyra during the set of Cheerleader, Warsaw, 2006. Courtesy: Zachęta National Gallery of Art, photo M. Oliva Soto.

So, how to re-read Kozyra nearly twenty years after her debut? Perhaps the most perverse solution would be to return to her use of the self in Pyramid of Animals, her body connecting the realm of representation with everyday reality, in which the abstract concept of deconstruction is legible, but also trips over the clumsiness of the individual, culpable body. On one side, the body performs, or tries to perform, its possible many selves; on the other, it is subject to the discipline and punishment by apparatuses of social control. However, what this mediation process can possibly promise is that with the constant exercise of the self/-ves, dreams will not only come true in art.

Pingback: Katarzyna Kozyra | Martina Vermorel

Pingback: This Week’s Artists | feministartblog