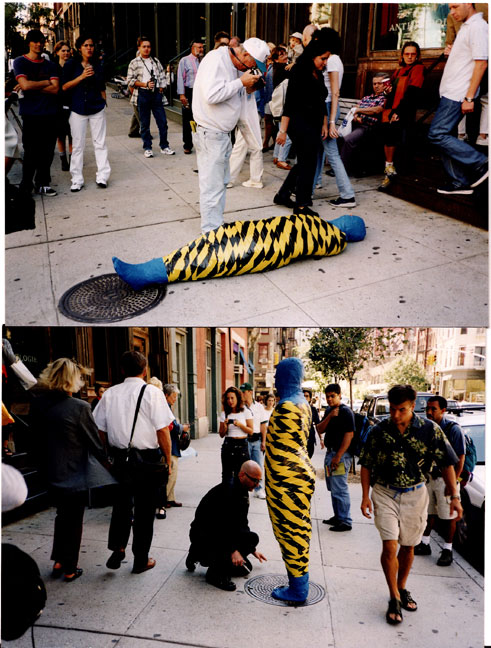

Hunter Reynolds. Mummification Performance from the Downtown Arts Festival, 2000 (Courtesy of PPOW Gallery)

In today’s art world, a majority of major artists have at least one or a team of assistants that tend to do most if not all of their art-making for them. Having written articles on a wide variety of artists and worked in a number of art fields, I’ve witnessed artists who don’t even touch their work. In response to this growing trend of artists not doing art, for these next two weeks I’m going to highlight the artistic processes of a few inspirational artists who push themselves, both physically, emotionally and sometimes through illness or injury, to create, whether through drawing, painting or performance.

Known for his physically strenuous performances–from his caged performance as his alter ego Patina du Prey to his Mummification performances, where he is completely wrapped in colored tape and sometimes moved throughout the city–Hunter Reynolds’s work questions issues of gender, sexuality, HIV/AIDS, mortality and rebirth. After surviving two strokes related to being a longterm survivor of HIV/AIDS, which forced him to quit making art for six years, Reynolds has continued to create art, having several exhibitions and two solo shows at PPOW Gallery and Participant Inc., and perform, with his last Mummification performance featuring Reynolds being placed in the center of 10th avenue in front of moving traffic.

I spoke to Reynolds about the progression of his performance art, how to preserve and document performances and the ability of art-making to deal with emotional and physical pain.

Emily Colucci: Looking at your artistic process, most of your work has been performance art, often fairly confrontational performances that incite audience reaction through the use of your body. How did you first begin working in performance art?

Hunter Reynolds: One of my teachers was Chris Burden who is such an insane guy so the whole idea of these crazy performances he was doing. I was going to these performances in the scene of Downtown Los Angeles even before I thought about doing performance art myself. Mike Kelley, Paul McCarthy… Then I started looking at Laurie Anderson, Vito Acconci and action-based performances that were more body-oriented. Those were the things I started gravitating towards. Then I was a member of this class assignment in a sculpture class that turned into a performance art group. A group of us got together and formed this performance/installation/tableau called Unarmed that was about nuclear disarmament. We created these scenes of very apocalyptic scenarios. Very Mad Max. We became this thing in LA for a year and a half and I learned a lot of how to make my body into a sculpture-kind of object, pretending to be dead and then using very subtle things to interact with the viewer. There I started responding to my school and my performances in school were tests. Instead of doing a final written test, I would do a performance and I wouldn’t tell the teacher about it and I would do it right in the class.

EC: What were these performances like?

HR: One of them was I had to work a full-time job when I was in school and I was navigating my work life with classes which were 15 minutes from where I work so I was always late. One of my teachers hated me. I hated her and the class. It was a collage and assemblage class. We had this final project and we could never finish it till the end then we had to finish it as a process piece and had to keep it going all semester. I tore the thing up and wrapped it up like a log of shit on the table and we were having the crit. She got to me and I said, “I hate this class, this piece.” I unloaded all this violence and anger at her. I said, “I feel like burning it,” and she said burn it. So I lit it on fire in the class. I threw it out the window into the yard. We all went out into the yard and watched it burn.

So then, we had one class left and I looked at her and said, “Its not finished yet.” I decided to really show her how I felt about the piece and the class and her. I decided to go with the idea of processing the piece further. I collected all the ashes and I got a small room and told her, “I’m going to do a performance and its going to be in this room.” Through the back door, I entered the room in a doctor’s smock with a light and a table, a blender, matt medium, a blender and a grinder. I ground the ashes up, entered the room then I poured it into the blender and then I drank it. And they all freaked out. Then I turned around and left the room. The idea is its going to continue to process and going to come out a bunch of shit like this class. So I got an A +.

Hunter Reynolds. "Patina du Prey's Drag Pose Cage," Simon Watson Gallery, 1990, fabric and steel. Courtesy PPOW Gallery.

EC: In the late 1980’s, you began performing in galleries and arts spaces as your alter ego, Patina du Prey. Performing enclosed in a cage or on a rotating stand, Patina du Prey confronted the audience with not only a live body in an art space but confused issues of gender and sexuality. How did the audience react to Patina?

HR: I got a variety of reactions. I found that during the performance when you set up parameters that are confusing, they’re not sure what’s going on, whether they’re part of it. That kind of tension and dialogue I really like. One of the first things I did was Jack Tilton was having this exhibition and I had put on a dress and laid down on the floor in front of the door so people had to step over me. I fell asleep and they thought I was a sculpture. They didn’t even think I was alive. So that whole thing, playing with people’s boundaries, making them uncomfortable but confronting them with something ordinary and familiar.

When I got into the cage what I found is that people wouldn’t even look at me, they’d see me at the corner of their eye. Then they’d look at pictures. So I was playing with that. Or they’d go into the back room and peek around the corner. I realized I was very confrontational. So, I played with veiling my face. I’d put toile all over it. All these variations of mystery, voyeurism confrontation of the self. It was fun to play with these parameters as a performance artist.

EC: One of my favorite series of your works that you’ve done four times this year is the Mummification performances where a team of assistants wrap you in tape like a mummy transforming you into an inanimate object, with no indication of a body other than your free arm that is not taped. Tapping into issues of death, rebirth and even fetish, the Mummification performances appear physically strenuous with your entire head covered. How did you start the Mummification performances?

HR: There was a gay leather bar called The Lure in the Meat Packing District and they had a night called “Pork” and a couple people I knew were involved. They had a performance night and had me do a performance in their club. What about what I do could be taken to a gay S & M club and mean something to them? So I got the idea to get mummified. It was an extension of other things I had been doing. It works as a butterfly and chrysalis thing. Doing something that’s expected to be done in a fetish club. People had been talking about it for years. And then, I got invited in the festival in France and that’s how they started.

In retrospect, it was the beginning of my life and my transformation that I wasn’t even aware of yet. It related to my psyche at the time. After I had the strokes and didn’t do anything for six years, how could I come back to performance art?

Hunter Reynolds. "Mummification Performance Skin," 2000. Plastic wrap, duct tape. Courtesy of PPOW Gallery.

EC: One of the major issues with performance art has always been how to document and preserve performances. As an artist who mainly produces performance art, how do you navigate these issues ?

HR: Performance art is an ephemeral thing. It only exists at the time it exists. No documentation will be what it was, which is interesting but it doesn’t mean it can’t be something new either. When I had my first show in New York after the strokes at Artists Space, I was wrapping my head around the idea that I might never get in it again, I’d never be able to perform this piece I had performed hundreds of times in the last ten years. I was sitting there one day really lamenting that and Marina [Abramovic] came in before her show at MoMA had opened. She told me she was wrapping herself in the idea of performance art and getting old. She said she was doing the whole show on re-performance. I went to see that show. Plus her setting this bar of performance art that no one’s ever done before. I waited for 3 days to sit in front of Marina. It was interesting for me to see a performance artist raised to super-stardom. I think it was fantastic.

EC: I saw your My 9/11 Mummification performance in Tribeca Park in New York. That performance in particular seemed to deal with trauma and rebirth. In a recent Huffington Post interview, you spoke briefly on using art to overcome pain. How do you use art-making as a way to deal with pain?

HR: Art-making, painting for me as a child was the first healing thing. It was something I learned to do when I was really young. My grandmother taught me how to paint oils when I was four. I immersed myself in it and lost time. Everything about it, the smell the distance of it, the isolation, being alone in it, got me through my childhood. The healing aspect of art making has always been in me. When I started dealing with things that I wanted to say with my art in the 80’s, my earliest installations were still combining paintings. I would use a lot of found art, making these text-things and photography. The issues back then were all about how to incite some kind of physical, emotional reaction for people through art objects. That was how I was navigating my practice back then. The AIDS crisis came in and all that pain of people dying and the anger and all that became a vehicle that pushed me to deal with those kinds of issues for myself. The physical aspects of the performance art plays with that physical pain but also the emotional paint of the psyche.

EC: Making art about the physical and emotional pain of HIV/AIDS has taken on a different context from making it at the height of the AIDS crisis and today. I’ve noticed that people of a younger generation seem to not have a real knowledge of AIDS and the AIDS crisis. What is it like making work that references HIV/AIDS today?

HR: I’m a long term survivor so there is this whole thing that is happening to me surrounding that which is people seem to want to dig it up and understand it and know about it. It’s a historical thing that happened 30 years ago and the younger generation are just finding out about it. The dialogue keeps going in a way.

Pingback: You Can’t Plan Fun: An Interview With Kenny Scharf | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Transcend The Skin You’re In At P.P.O.W.’s ‘Skin Trade’ | Filthy Dreams