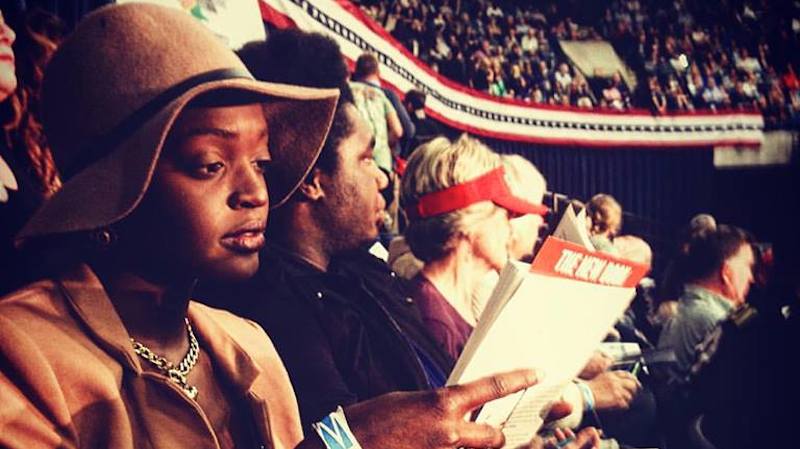

Johari Osayi reading Claudia Rankine’s Citizen at a Trump Rally, November 2015. Photo via Jezebel.

There’s a passage in Claudia Rankine’s 2014 novel Citizen that states, “Language that feels hurtful is intended to exploit all the ways that you are present.” Citizen’s narrative compiles sobering real-world scenarios where racism is both emotionally inflicted and visibly palpable, a sort of allegorical stigma carried by the bodies of Black individuals across generations of injustice and diaspora. In recent years, and not without specific challenges, digital technology’s professed hyper-visibility has prompted activists to demand that institutions be held accountable.

Rankine’s shorter stories portray interactions often referred to as “microaggressions”: a psychologist harasses a new patient upon arrival, assuming they had come to the wrong office; a concerned neighbor phones the police to report an unfamiliar man who had been asked to babysit; in a moment of frustration, a woman calls her friend the name of her housekeeper. In these instances, Rankine’s antagonists are indifferent to the point of oblivion, an assertive reference to how discrimination is so deeply embedded into culture that the perpetrator may not recognize that microaggressions, however unwitting, are at the root of cruelty. Through longer and more traumatic verses, violence grows inimical and premeditated. Written to the memory of America’s fallen martyrs—Jordan Russell Davis, Eric Garner, John Crawford, Michael Brown—their spirits materialize in Citizen as an admissible battlecry, expressing the urgency for frameworks that no longer fail to acknowledge brutality.

Glenn Ligon. Untitled (I Feel Most Colored When I Am Thrown Against a Sharp White Background), 1990-91. Oilstick and gesso on panel, 80 x 30 inches.

Rankine describes an unequal exchange, in which viewing a Black artist’s work becomes an experience inadvertently attributed to the biases of history. Printed as a diptych toward the center of the novel, Glenn Ligon’s 1991 painting reads, “I Feel Most Colored When I Am Thrown Against A Sharp White Background,” unequivocally communicating the frustrations Black men and women are made to feel in predominantly white spaces. Perhaps Ligon’s work also alludes to the art world’s long-held trope of the white cube, an ostensible reference today. Embracing provocations with the same passions that empowered many radical predecessors, Black artists are leading activist dialogues and redefining presence, intermixing scholarship and creative practice with the diverse politics of social media.

It’s paradoxical that a sharp white background is still the typical visual signifier of the internet despite the democracy it embodies, at least according to the world’s foremost technology companies. Puffy white clouds over a green field became Microsoft’s most iconic desktop background, originating in 1996 and aptly titled Bliss. The vast emptiness of a pale sky is an easily marketed metaphor, alluding to the promise that, in just a few clicks, anything the imagination desires can appear on a screen.

Charles O’Rear. Bliss for Microsoft XP, 1996.

E. The Avatar dwells in this satirical cyberspace, seated in a fluorescent-lit room behind an empty desk. A pseudonym of the prolific Philadelphia-based artist and activist, known as E. Jane or Mhysa, E. The Avatar appeared in a series of seven YouTube videos throughout 2015. In one topical recording, E. The Avatar discusses net neutrality—the principle that internet service providers should enable equal access to all content—as if it’s an emancipating ideology that could save them from digital obsolescence. And in a coy response that negates violence entirely, E. The Avatar draws parallels between Silicon Valley and colonialism in an online context: “Why doesn’t anyone pioneer here? We could all hang out together.” Language in cyberspace becomes neither hurtful nor exploitive but, rather, speaks to a utopia that only those who have truly faced odds can envision.

What gets primarily erased from popularized internet-as-idyllic-space analogies are the systemic underpinnings of data-driven surveillance, working to categorize individuals into demographics and imposing structures never removed from reality. In particular, social media can be said to ignite microaggressions through increased accessibility coupled with little distinction between online and offline sociality, an expanding issue that should not be minimized due to digital mediation. Through the monitoring of social media patterns, Black Lives Matter protests have been preemptively shut down, and predictive policing has resulted in unfair arrests and accusations. These examples prove that regardless of nuanced development procedures, assuming data-mining technologies were designed without incorporating existing prejudices is unrealistic.

E. The Avatar. Screenshot via YouTube, 2015.

By proffering a pseudo-safe space, E. The Avatar reveals the ironies of considering the internet as an idyll and instead reiterates associations between social identity and someone else’s profit. Building upon the video series, E. Jane created several apparel designs intended for sale, symbolic of a commodification of Blackness by the advertising industry’s pursuit of viral trends. Reflecting on this predicament, they recently told the arts magazine AQNB, “Being wearable kinda just feels like being Black. The Black body being a fungible product was fundamental to the rise of America.” Creating Facebook advertisements to deconstruct the multilayered security concerns resulting from the site’s algorithmic gaze, E. The Avatar has pegged interpersonal microaggressions as extensions of brand co-optation and accelerated commercial hype.

The processes by which online ads appear are complex and unique to every person, but they certainly reflect policy decisions that favor marketers and not users. Google has defined “affinity audiences” as “aggregated consumers who have demonstrated a qualified interest in a particular topic.” Similarly, Facebook Exchange guarantees dynamic marketing by tracking a user’s previous search engine activity. While both corporations’ policies explicitly state that profiling by race or gender is prohibited, targeted ads are more than potential classifiers: they’re evocative of how surveillance continues to materialize consumer choices as a politic of difference. And as highlighted, such forms of unwarranted observation can carry severe consequences for people of color.

E. Jane’s Facebook Page. Screenshot of a 2015 advertisement.

E. The Avatar contests intolerant circumstances through critical awareness, largely by distinguishing surveillance, as a form of power, from presence, as a form of affirmation. Perceptive, ad-copy-inspired phrases (like, “E. The Avatar gives you that empathetic ‘I like Black girls’ look you have been searching for”) work to reclaim Black identity from methodical discrimination, demanding impartial visibility while rejecting the forces of control that seek to marginalize it.

It is possible that an activist’s mediation of the tools that promote exploitation can be interpreted as a form of resistance. It is possible that egalitarian efforts on social media can destabilize difference through communication and awareness. It may even be possible that new works created with an enigmatic techno-utopian spin can eventually alleviate the biases that informed Rankine’s thesis. E. Jane’s work realizes this potential cultural renewal, or, as the artist tweeted: “Dreaming up new futures feels like the only way to get to a future I can imagine looking forward to. And I want to live.”