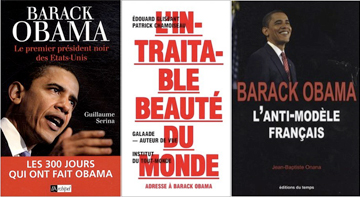

A few recently-published French titles about the rise of Barack Obama (from left to right): "Barack Obama: Le premier president noir des Etats-Unis" by Guillaume Serina; "L’intraitable beauté du monde. Adresse à Barack Obama" by Édouard Glissant and Patrick Chamoiseau; and "Barack Obama: L’anti-modele français" by Jean-Baptiste Onana.

At the École des Beaux-Arts de Nantes (Nantes School of Art), I am teaching a course called “Contemporary Art in the United States, 2000-Today.” The premise of the course is to give students an introduction to recent American contemporary art while also giving them an opportunity to practice their English. While we will consider art made during “the Bush years” (2000-2008), I am also interested in the notion of “today” as a moving target.

The first week of the course coincided with l’investiture (inauguration) de Barack Obama. If there was Obama fever in Nantes during the week of the Inauguration, it was subdued. My French friends and colleagues shared their impressions with me, which ranged from joy…to envy…to apathy…to skepticism about the hype…and finally, to doubt as to whether France would ever elect a black president. In France under President Nicolas Sarkozy, like in the U.S. under Bush, citizens have become deflated, prone to anger, and weary of the government’s lack of response to public complaint.

In class, we watched the first several minutes of Barack Obama’s inaugural address. I invited the class to consider Obama’s address as a work of performance and spectacle. Our conversation centered on the symbolic trappings of the inaugural ceremony. First, there was the issue of the canon firing, which the students found inexplicably silly. They questioned why the inauguration would employ such an anachronistic weapon. For example, why don’t the aesthetics of the inauguration change to reflect contemporary sensibilities? The canons alluded to military salutes from the time of the nation’s founding in the late 18th century. Perhaps it was the sheer anachronism of these symbols that situated Obama in the lineage of American history on Inauguration Day (and was a reminder that some of our first Presidents were slave owners).

The students also took note of the many American flags on display, both on the National Mall and waved by the cheering audience. They explained that in today’s France, to prominently display the French flag is a gesture towards nationalism and the FN (National Front) political party. The FN, led by Jean-Marie Le Pen, promotes an anti-immigrant and racist nationalist agenda and opposes France’s participation in the European Union. The younger generation doesn’t associate with the flag as a symbol of French identity.

Also, unlike the American flag, the French flag’s origins are not explicitly linked to the nation’s independence and founding. In fact, how could a single modern flag represent a history that accounts for Gaulic tribal occupation, Roman rule, monarchical succession and overthrow, and numerous revolutionary governments? The notion of historical “change” in France could be said to be more cyclical than linear in nature. As the saying goes, the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Claire Fontaine, "Sans Titre (Identité, Souveraineté, Tradition)," installation, flags, dust, poles, 300 x 200 cm, 2007. Courtesy FRAC Nord - Pas de Calais and Galerie ERBAN. Photo credit: Marc Dieulangard.

In a recent exhibition at ERBAN’s gallery called Over the Rainbow (curated by Benoit Villain), I saw a clever installation by Parisian art collective, Claire Fontaine, that plays on the symbolism of the French flag. The parenthetical title, Identité, Souveraineté, Tradition (Identity, Sovereignty, Tradition) is an inversion of the French ideals of Liberté, Fraternité, Egalité (Liberty, Fraternity, Equality) that speaks to the tricolor flag’s contemporary signification. The exhibition text provides more context about Claire Fontaine’s work:

Claire Fontaine is a collective founded in Paris in 2004. Taking their name from a popular brand of school notebooks, Claire Fontaine declared itself a “ready made artist” and began to elaborate a neoconceptual version of art, with their work often resembling the work of others. Using neon, video, sculpture, painting and writing, their practice could be described as an overt questioning of the political impotency and crisis of singularity that seems to characterize contemporary art today. For the exhibition at the Espace le Carré, their work presents three French flags, with the colors modulated as on the bar of a battery charger. Nationalist symbol, military banner, but also color code, the flag is an element that unites different strata of identification and can also suggest painting. Flags have sometimes been created by painters or explicitly used by others (David, Delacroix). In the context of this project, the work offers an interesting introduction to the notion of colors (in the military and pictorial sense) in relation to the work of Cédric Noel.

In class, the students and I also discussed Obama’s MySpace and Facebook profile pages to understand his use of youth-oriented social networking websites. A debate about the inclusion of The Fugees in Obama’s list of “Favorite Music” led to a conversation around the “marketing of authenticity” in political campaigns. Some of the students distrusted representations of a politician as anything but. This goes for politician as friend or politician as celebrity icon. The students pointed out that I was only showing them promotional materials from Obama’s campaign. So we looked up “Barack Obama +conspiracy” on Google. The anti-Obama discussion threads that we read put the message of “Hope” starkly in context.

Screenshot of President Nicolas Sarkozy's website (www.sarkozy.fr), 2009.

President Nicolas Sarkozy’s website, sarkozy.fr, is another prime example of the application of user-friendly web-interactivity in a political campaign. Sarkozy’s campaign website, an über-personable Web 2.0 extravaganza, answers (and in fact, predates) Obama’s slogan “Change We Can Believe In” with the slogan “Ensemble Tout Devient Possible” (“Together Everything Becomes Possible”).

President Nicholas Sarkozy, "Merci de m'avoir fait confiance", video address on NS.TV, 2007. The subtitle of the video reads: "I will not deceive you, I will not betray you..."

The aesthetics of political authenticity never looked more friendly.