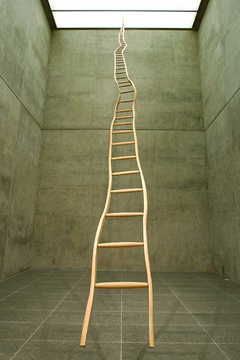

Martin Puryear, "Ladder for Booker T. Washington," 1996. Ash, 438 x 22 3/4 x 1 1/4 inches. Installation view at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas. Collection of the artist. Photo by David Woo. © David Woo.

It’s easy for contemporary art cynics to criticize the Bushesque debasement of language that goes on every day in the art world. I’ve actually started to take to the byzantine charms of the polysyllabic press release; there’s something endearing about the wild tilting at the semantic windmill that goes on, something loveble about its trumped-up claims to elucidate the work at hand. (Here’s a fun game: read out a press release to a friend and get them to draw what they think the art described looks like). What is starting to grate is the blanket use of the term practice to describe what an artist does. It’s fascinating to trace the mutation of the word from output to work to its current incarnation, which is more redolent of the work of town planners, or pharmaceutical companies, or small-town doctors, than it is of visual artists. Certainly the linguistic evolution (I use the term advisedly) is a testament to actual changes in the way artists work (and yes, many artists are sort of like town planners these days). The problem comes up when artists whose work sits outside of this rather narrow definition of the daily grind have to be discussed. You might call what Fred Wilson does his practice, but how about Peter Doig? Barbara Kruger, yes, but Richard Serra? And how about Martin Puryear?

I think that the distinction that I’m trying to examine is the age-old one between the maker and the thinker (and, perhaps, to explore the dangers of thinking of them as mutually exclusive). During the Italian Renaissance, Leonardo da Vinci made a point of distinguishing between the painter and the sculptor in his Treatise on Painting from the late 15th century. In what was almost certainly a dig at his younger rival (and quite successful sculptor) Michelangelo, da Vinci described sculpture as a “wholly mechanical exercise.” Marcel Duchamp’s final nail in the coffin nearly a century ago made discussions of technique redundant (so we’re told). However, the “mechanical exercises” linger on while the words used to describe them now seem archaic and a bit fussy. It’s certainly the case that the art world’s lexicon of adjectives is an exclusive one that presupposes a certain jumping-through of hoops. Puryear is a good example of an artist for whom the standard contemporary art vocabulary isn’t nearly elastic enough. So how to discuss his work?

Martin Puryear, "Plenty's Boast," 1994-1995. Red cedar and pine, 68 x 83 x 118 inches. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Purchase: The Renee C. Crowell Trust. Courtesy McKee Gallery, New York.

Looking at Puryear, I was reminded of certain passages in the writings of the late Italian writer and chemist Primo Levi. There’s no biographical or even national commonalities between the two, and I’ve no idea whether or not Puryear is familiar with Levi’s books, but there are a couple of quotes which could perhaps illuminate the historical strangeness of Puryear’s purview—and the need for a better vocabulary to address what he does. This first from Levi’s 1987 book The Wrench (published in the US as The Monkey Wrench). The book’s protagonist, Faussone, is a rigger who tells various anecdotes about his working life over the course of the book. Faussone’s attitude to his work elucidates the value of “the touch” in a way that sheds light on Puryear’s work:

I tell you, doing things you can touch with your hands has an advantage: you can make comparisons and understand how much you’re worth.

Martin Puryear, "Deadeye," 2002. Pine, 58 x 68 x 13 inches. Private collection. Courtesy McKee Gallery, New York.

Another example of this unexpected parallel is Levi’s essay “A Bottle of Sunshine” from his 1985 collection of essays, Other People’s Trades. In this essay, Levi examines human beings’ peculiar ability to create receptacles designed with an eye to “foresee the behaviour of matter”:

…man is a builder of receptacles; a species that does not build any is not human by definition. In short, it seems to me that to fabricate a receptacle is…exquisitely human.