You can’t have a job in museum education without being asked, at some point, “What’s that worth?” Depending on the questioner, how well the tour went, and how loyal you’re feeling, your answer can vary wildly. I’m currently on a sliding scale from “Some old bits of cloth and mashed beetle-wings – about a pound, tops,” to “More than you and I combined will ever make in a lifetime of dishwashing.” Whatever amount you quote, the reaction is always incredulous, as well it should be. The very idea of art being worth anything, to a mind trained to associate fiscal worth with functional value, is ludicrous, since the apparatus that assembles value in art is a fuzzy one, a sum of socialized activities (writing, talking, thinking) of no translatable worth in the “real” world, and of no logical equivalence to that pile of rags in the corner of the gallery or picture of a flushed duke in a periwig. Having said that, though, socialized value is what drives the majority of our most meaningful purchases anyway: we spend that much on a sports car not because it can do 0 to 90 in a millisecond but because its perceived value will magically hoist us up a social rung or two and maybe make that girl more forgiving of our “little problem.” Like that car, the value of art is the sum of the nebulous air around the object—or non-object—an air thickened by press releases, scholarly articles, PhD proposals, chatter, and banter. The experience of art is both facilitated by this background noise – the literal availability of works of art to public view – and obscured by it. It’s figuratively harder to see works of art for all that obfuscating murk.

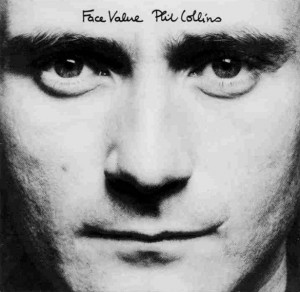

Art and money may not be equivalent, but they are remarkably alike. As Swiss artist Daniel Spoerri put it, “in exchanging art for money, we exchange one abstraction for another.” Both art and money are predicated on a fluctuating definition of ‘face value,’ their apparent worth subject to the vagaries of history. In the current economic climate it’s tempting but unhelpful to see certain works of art as inextricably linked with a Machiavellian economic system simply because they proved popular with CEO’s looking for something to stick in the atrium (1980s painting has the same problem of association). In art and economics, stability is an illusion perpetuated by those who stand to gain from it, something made literal in Damien Hirst’s most recent work (the diamond-studded skull, the gold-hoofed calf). It’s hard not to see that work in particular as equivalent to and inextricable from its market value, as parodied in this broad but timely April Fools’ email (note the author’s name, haw haw!) that did the rounds this week:

AIG FINANCIAL SERVICES MANAGERS DECIDE TO GIVE AWAY BONUS MONEY TO SUPPORT THE ARTS BY BUYING UP ALL OF DAMIEN HIRST’S “ART”

By Sue Themnow

Realizing that they were about to be hung in more then effigy, the top managers of AIG’s London Financial Services division decided that they would give away much of their bonuses to a worthy charity: buying up all the excess Damien Hirst art that has flooded the market, thus saving White Cube and hundreds of now-broke art collectors. Any left over funding will go to buying up Thomas Struth pornographic reprints and big flower photos.

“We knew that all those polka dot paintings and medicine cabinets were even more worthless than those insurance policies on derivatives that we were selling, so we felt we would help the economy and the arts, by buying up all of Hirst’s art and burning it,” said one former AIG bundler, “that way we could make a charitable contribution to culture and save the art market from its biggest blunder yet. Plus get a great tax write-off on top of it, so we don’t even have to pay any taxes on these bonuses.”

“We thought about giving the money to some real charity in the U.S., but then, we said, ‘What the heck, we’re Brits and ex-Pats and the American taxpayers and the U.S. Congress can kiss our big British butts.'”

Yes, it’s anatomically hyperbolic and comedically suspect, but what this reveals is the extraordinary sleight-of-hand that takes place during an economic boom: art (like insurance policies or sub-prime mortgages) suddenly appears to have intrinsic value and market stability, despite all historical evidence to the contrary. When Marcel Duchamp exhibited Fountain, his unadulterated urinal, in 1917 and ‘signed’ it R.Mutt, a phoenetic rendering of the German word armut (poverty), he was acknowledging the extent to which material value had been eclipsed by socialized value. Historically, the disparity between material cost and artistic value has its roots, perhaps predictably, in Renaissance Europe, when hard-nosed wool traders and bankers scored intellectual points through the patronage of experimental artwork. The material value of art – until then inextricably tied to the religious significance of the object – gradually became eclipsed by the cult of the individual, buoyed entirely by socialized energy generated through the writing, talking, and thinking of the mercantile middle classes (hence the term “the chattering classes”). Since then, false systems of accreditation have been repeatedly raised and collapsed. The 18th-century Salon system equated value with scale and virtuosity, for instance, inadvertently engendering Impressionism.

Art of today is in need of developing its own system of accreditation outside of the domineering influence of the capricious markets. How this will appear is not clear. I’m not sure Holland Cotter’s assertion in the New York Times recently—”‘Quality,’ primarily defined as formal skill, is back in vogue, part and parcel of a conservative, some would say retrogressive, painting and drawing revival”—is either entirely true or, if partly true, entirely to be trusted. Ill-defined notions of “quality” set up assumptions of comparative value of which we ought to be suspicious. The less the art world imitates the financial world, the better. Let’s get started.