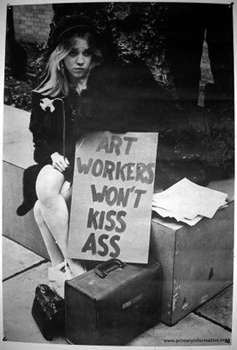

Art Workers Coalition, "Art Workers Won't Kiss Ass," 1969, primaryinformation.org, 2008

Last September, as part of Creative Time’s Democracy in America: The National Campaign event at the Park Avenue Armory, activist group Working Artists and the Greater Economy (W.A.G.E.) stumped for the rights of artists to be compensated fairly for their labor by art institutions in the United States. The economy has taken a bigger hit since then, which makes W.A.G.E.’s work even more important. The Brooklyn-based collective was formed in 2008 by artists A.L. Steiner, K8 Hardy, and A.K. Burns, and the group’s expanding membership includes artists, performers, independent curators, and all others who share their cause. W.A.G.E. cites exemplar, working models beyond our borders overseas and overhead—organizations such as the Canadian Artists’ Representation / Le Front des artistes canadiens (CARFAC), whose efforts resulted in the 1988 Canadian Artists’ Representation Copyright Collective (CARCC), which legally established a fee schedule for artists to be paid every time their work is exhibited at a gallery, museum, or institution that receives federal funds.

As a cultural worker myself, I am all for such a system that treats and compensates artists like true professionals. However, I am not totally convinced that something like CARCC could effectively work here, though something is better than nothing. CARCC’s established fee schedule affected only galleries and museums that received some kind of federal money, so commercial galleries don’t apply. And in the United States, funding for the arts is so abysmal that it seems a radical shift in the structure of the arts umbrella is truly what is needed.

Recently, I conducted an interview with W.A.G.E. via email, and gathered their thoughts on some of these issues.

TRONG G. NGUYEN: Who are the founding members of W.A.G.E., and what are your backgrounds—have you always been political activists and artists?

W.A.G.E.: Working Artists and the Greater Economy (W.A.G.E.) was formed in Brooklyn, NY in 2008. We’re a group of artists, performers and independent curators who believe that we should be paid for our labor by U.S. art institutions. The group is open to anyone who would like to join that cause, and embraces seasoned activists, non-activists and anything in-between.

TGN: Do you view W.A.G.E. as an art collective or lobbying group?

W.A.G.E.: We’re an activist and consciousness-raising group.

TGN: W.A.G.E. participated in Creative Time’s Democracy Convergence Center event last September, before the elections. Tell us more about your performance and what you hoped it would accomplish. Was it preaching to the choir, or did you felt the event actually did some good beyond the art world?

W.A.G.E.: We find that although we’re speaking to our peers, the issues we raise—and strategies we’re attempting to develop—weren’t being actively discussed in the arts community; therefore, people have responded with a huge amount of support, surprise, and relief to hear a voice that acknowledges their specific situations as artists, performers, and arts workers.

TGN: You reference the Art Workers Coalition of 1969, which criticized MoMA’s collecting practices and focused on artists “working conditions” in general. Although well-intended, a number of the artists who were initially involved have essentially become entrenched in the gallery and museum systems they previously railed against. Do you think this intrinsic hypocrisy needs to be dealt with before the system can truly be changed? And if so, how?

W.A.G.E.: This question is framed curiously, but indicative of the perception of arts workers both within and outside the arts community. W.A.G.E. finds it unnecessary to frame this as a dichotomy: one doesn’t need to be outside the system to criticize or effect change. We’re comprised of, and welcome, all artists and arts workers- regardless of income, or market notions of career status or notoriety. We’re not eschewing market success. Our cause is to counter the hypocritical assumption by U.S. public and private art institutions that artists and arts workers don’t require monetary compensation for our work. Hollis Frampton addressed this in a letter he composed to MoMA in 1973 where, among other things, he outlined the workers in all the industries he supports by merely making his film work; ironically, this includes not only film manufacturers, processing labs, print labs, etc, but also the arts administration staffers as well. As noted in his letter, he was the only one not being paid for his work. The museum offered to pay him in “love and honor.” This was 35 years ago and overall, the terms have largely remained unchanged—except for the cost of living.

TGN: That’s gross, of course. But I also think there are real economic problems facing our institutions. The letters I was referring to spoke of eradicating the art world and exhibition of artwork completely (Carl Andre), or calling out against the decision to build an art “skyscraper” in midtown, e.g. MoMA, and instead open small community museums in “various loft-districts of the city” to solve financial problems (Hans Haacke), among other well-intended recommendations. Thus many potentially influential voices might guide the collective mission astray despite “solidarity.” By this I mean that we must avoid a Sarah Palin syndrome. Who takes the reins to ensure that the mavericks don’t run wild on the real issues? I imagine that eventually there will be lawyers involved or others in prime position to make such changes if we are to truly effect legislation. Or can cultural workers realistically do it themselves?

W.A.G.E.: Again, this question assumes the same position as the previous one—that things can’t be changed, improved or fixed because it’s too scary, or impossible, or unreasonable. We’re not the AWC, nor are we Sarah Palin. We’re also not a “charity,” or other-wordly creatures who survive on air and live in a dream-state. To be paralyzed by the idea of forming a movement to advocate on one’s own behalf would be a sad and destructive state of affairs. During both good and bad economic times, things have stayed the same. There’s an incredibly passive, unimaginative, hypocritical relationship to change in this country when it comes to economic issues. We see the current hysteria—both in perception and reaction—to shifts in the economy and employment markets. There are over 100,000 non-profit art institutions in the U.S. alone. A majority of the institutions artists deal with charge entry fees, like a movie theater or performance space. And the institutions, whether non-profit, for profit, or not-for-profit, are deceptive concerning money issues. One artist just recently asked if there was a fee and was told yes, since she asked, they were obliged to give her and all the other artists in the project a fee, but that if she hadn’t asked, they were not obliged. What kind of behavior, or “policy,” is that? What cultural “norms” produce such behavior? It’s detrimental for us to pretend that this system is just fine the way it is. We’re not looking for a bailout, or devising systems to steal money, or opening off-shore accounts in the Cayman Islands; we’re asking to be factored into our own equation, paid fees for honest work, to be equal participants in the economy. We cannot afford to be left out.

TGN: In Canada and certain European countries, there exist laws that ensure basic artists rights, such as getting paid to exhibit artwork in an institution and not-for-profit spaces, based on the budget per show. Do you think this truly works, given that other factors such as shipping costs and insurance would rule out exhibiting many works in the first place—e.g. it would be easier and cheaper for institutions to show a photograph versus a giant sculpture?

W.A.G.E.: European and Canadian institutions haven’t stopped showing large-scale works merely because they pay artist fees or because they have to organize their budgets around such considerations. As your question implies above, we are placed in the position of accepting that there are no alternatives to the current U.S. system—i.e. there must be a no-fee system because otherwise, the system will not work. We absolutely don’t believe this is true, and it follows the model of other market-economy lies currently haunting the American worker. We can look to other countries’ institutional models to know that W.A.G.E.’s demands aren’t some crazy, untenable dream. They’re based on the solid fact that artists and arts workers, elsewhere in the world, get paid by the institutions that request their services. If there were artist fee allocations, systemic policies, and oversight, or merely any degree of budgetary transparency in the U.S., W.A.G.E. would be obsolete. So we can no longer afford to abide by “feelings” on these matters; it’s more about where priorities lie. Institutional staff members, advisors/board members, gallerists, gallery administrators, and collectors are our community. They must serve as our advocates rather than our adversaries in maintaining a robust arts community, not focusing solely on the trading of objects and objects as the only manifestation of “investment.” The current economic system must not succeed in squeezing the art worker out of U.S. communities—communities that we enrich.

TGN: I do believe an alternative exists, but I don’t necessarily think the European and Canadian models supply the answers here in the States because of root differences like economic systems (capitalism/socialism) and population size. Are there any feasible models that don’t yet exist that you could see working?

W.A.G.E.: The model is that budgets must include fees for services rendered. Humans are innovative, imaginative, organized, and intellectual. We’ve accomplished all kinds of miraculous things over the past couple millennia, and it’d be absurd to pretend that paying artist fees is an impossible task. To assume that art institutions cannot allocate part of their budgets for fees is at best naive, and at worst criminal. If an institution works with 200 artists per year—solo exhibitions/2-person/group shows, commissions, screenings, independent curation, performances and lectures—there’s most definitely a way for them to take a percentage of their budget and allocate fees and, separately, expense, travel and/or accommodation monies for those projects, just as other sectors of the institution’s budget require organization. Fees for a small-to-medium institution can range anywhere from $50-$75 for such things as screenings, $75-$100 for group exhibitions, $150 for lectures, $300 for solo exhibitions, etc. and upwards, depending on the institution’s size, budget, and annual plans. When the staff at the institution contacts cultural workers, they should have clear amounts—whether it is solely a fee, or a fee plus expenses, travel, and accommodations if that person resides in a different city than the institution’s location—that will be offered for participation. Everything up-front. If the artist, performer, or independent curator needs to spend more on the project and raise more funds, then it is their choice to do that. If the artist is prominent and requires higher compensation, the museum can negotiate with that artist and explain their compensation policies. Or offer Target or another corporation or donor a tax write-off to establish the “Accomplished Artists Visiting Fund.” Or conversely, the artists can donate their fee back to the institution’s budget and get a tax write–off, if it’s a non-profit. But in the very least, the institution must establish base fees for all arts workers. There are many, many options. We’re not talking about artist fees that break the bank. We’re demanding that a reasonable system of compensation and mutual respect be firmly implemented in U.S. art institutions as a matter of policy. That effort corresponds logically and fairly with the economic system we’re participating in, and it would be best if these institutions took it upon themselves and were not forced to complete this task. We’re holding discussions and conversations with people here, nationally, and internationally who are working on the same issues, and devising strategies in order to effect change.

TGN: How do you feel about things like the Artist Pension Trust?

W.A.G.E.: The Artist Pension Trust is not a resolution to the problems we’re addressing.

TGN: What do you feel are the most pressing issues for contemporary artists and independent cultural workers in the present economy? What can they do to mobilize?

W.A.G.E.: We speak specifically for artists in the New York area. The market has dropped out, so the stakes are high for economic survival within our communities. When there’s a smaller market, the issues we raise are more apparent. Art will continue to be exhibited, so systemic policies and priorities must change to support artists economically, rather than refusing to compensate or advocate on our behalf. The institutions we work with and for, without receiving compensation or encountering refusal of payment, are dependent on us for their livelihood. Join W.A.G.E. Ask questions, and raise concerns and consciousness regarding your economic livelihood in your business exchanges. Advocate on behalf of yourself and your peers in your dealings. Sometimes asking for compensation miraculously produces some.

TGN: You’ve been holding town hall-type meetings at Judson Church to discuss many of these issues. Has there been any progress with this process?

W.A.G.E.: Yes. We’ve taken the discussions and subsequent feedback, and are developing our first survey—information, knowledge and transparency will allow us to advocate. We’re continually spreading the word and our visibility.