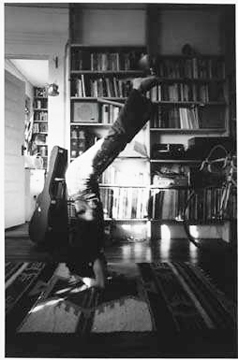

Adrian Piper, "Mythic Being Doing Yoga," 1975

Everyone has heard about the value of “being in the moment,” letting thoughts of the past and worries about the future drip away while focusing on the here and now. There are some tried and tested techniques for reaching this state, some of which are easier to engage in than others: practicing yoga, meditating, taking drugs such as Ecstasy that emphasize the sensory and empathic over and against the cognitive, having really good sex, eating a piece of chocolate so amazing you can’t possibly think about anything else. Jon Kabat-Zinn has secularized and popularized meditation techniques of being aware of one’s sensations, feelings and perceptions in the present moment, and the use of these mindfulness techniques in medical care. Mindfulness is now credited with a host of mental health benefits including anxiety relief, soothing the cravings of addiction, curbing depressive ruminations, treating eating disorders, and reducing self-harming behaviors; it also has applications in education, sports, and corporate environments. New York Times #1 bestseller The Power of Now by Eckhart Tolle has brought mindfulness to prominence within the popular project of self-improvement, albeit peppered with promises of enlightenment that probably won’t be delivered.

Art is occasionally called upon in guided mindfulness meditation exercises, which sound something like this: “Look at the painting in front of you. Notice the colors, the interplay of light and shadow. Let your eyes rest on a particular detail; notice everything you can about it. If you find yourself thinking about anything, don’t judge your thoughts: just notice them and let them go, over and over again. Look at the thickness of the paint. Can you see the brushstrokes? Notice how the painting makes you feel. Sit with that feeling,” etc. Although this might be a pretty good way to look at a Rothko, one might wonder whether mindfulness has a place in art that works in a different way.

Mark Rothko, "Four Darks in Red," 1958

If we think art in terms of mindfulness, perhaps part of art’s value is its capacity to direct our attention to a particular object, image, sound, environment, or situation. While most practices of mindfulness limit their focus to shifts in the consciousness of the individual; some artworks demand consideration of interpersonal mindfulness, the value of an attentional focus on the here and now of the social. While artist Adrian Piper is well known for having been a practitioner of yoga since the 1970s, mindfulness is deployed in her work in a way that expands beyond individual practice and moves to the interpersonal, making certain moments of social engagement very present. Piper describes the “indexical present” as a directed attentional focus on the immediate here and now; basically mindfulness that is pointed to a particular moment, a moment of contact.

In perhaps her most famous piece, Cornered (1988), Piper creates a situation in which the gallery-goer is confronted with the fact of the artist’s blackness, and the possibility of the viewer’s own unknown latent blackness. Indexical language such as “I, you, we, let’s, here, now” is used to implicate the viewer in an engagement with the here-and-now.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yUJ8MhXTwtI]

Expressing the ways in which her interest in the personal, particular interaction between ethnic or cultural others marks her prolonged fascination with the indexical present, Piper writes, my work springs from a belief that we are transformed—and occasionally reformed—by immediate experience, independently of our abstract evaluation of it and despite our attempts to resist it.” She frames this work specifically in terms of the capacity for art to act as a catalyst, which is to say that “it promotes a change in another entity (the viewer) without undergoing any permanent change itself…the work as such is nonexistent except when it functions as a medium of change between the artist and the viewer.

In Piper’s Catalysis series from 1972-73, she staged a number of public performances on the subway and city streets that forced a confrontation between viewers and the artist’s body in various abject states. She rode the subway with a towel shoved in her mouth, and walked through the streets of New York and went shopping at Macy’s with “Wet Paint” painted on her clothing, among other experiments. These actions exaggerate and make explicit unconscious operations already in play in the here-and-now on the part of both the artist and the public in the moment of performance. Attention is directed to Piper’s process of self-presentation as an object and the viewing public’s confusion, disgust, and fear at the scene of ambiguity, ‘racial’ and otherwise.

Adrian Piper, "Catalysis III," 1970

Adrian Piper, "Catalysis III," 1970

In Piper‘s 1986-1990 Calling Card performances, she would hand this card to people she encountered in everyday life who made racist comments in front of her at dinners and cocktail parties:

Adrian Piper, "My Calling (Card) #1," 1989

One part guerilla performance, one part social intervention, Piper’s Calling Card extends the practice of her 1970’s Catalysis works into an even more direct and intimate confrontation with social and interpersonal encounters at the scene of ‘racial’ recognition and its lapses. In her writings, Piper talks through her logical process which eventually led to the instantiation of the Calling Card performances; she recounts the extreme discomfort she experienced in various other ways of handling the recognition/non-recognition of her blackness. The indexical present instantiated by her work seemed to act as a catalyst for social mindfulness, awareness of the here-and-now of interpersonal relations.

This snaps me into mindful awareness of the fact that yes, art has value.