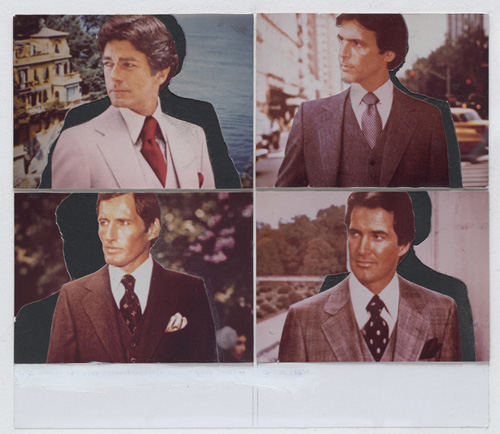

Richard Prince, "Untitled (four single men with interchangeable backgrounds looking to the right)," 1977. Mixed media on paper. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

As summer officially winds down, I can’t help but note that 2009 marks one very significant anniversary that seems to have been somewhat underappreciated, if not totally overlooked here in New York. I’m not talking about this the 400th anniversary of Henry Hudson’s historic exploration of the New York region, which also seems to have slipped by with relatively little fanfare. While perhaps not of this same scale, the underappreciated anniversary to which I’m referring does, nevertheless, mark an occasion that forever changed the course of art history. It is, after all, one hundred years ago this year that the first Futurist manifesto was published—a seismic proclamation that signaled the coalescence of a group that would alter the landscape and the trajectory of modern art (this group’s lessons and legacy are still being assessed). Although a major exhibition is irculating around Europe at the moment to observe the occasion, here in America, the centenary has been greeted with a somewhat muted response by institutions from which one might have expected a more robust commemoration (MoMA, wherefore art thou?).

While there was no centennial celebration to be found, one of the better commemorative exhibitions in New York did in fact highlight another group of radical, young artists whose lessons and legacy are also still being absorbed. I’m referring to the The Pictures Generation: 1974-1984 show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art earlier this summer. This exhibition, however, felt a bit like the anniversary that wasn’t, as it commemorated and expanded upon Douglas Crimp’s landmark Pictures show. But it did so, somewhat peculiarly, two years after the thirtieth anniversary of that now legendary exhibition at Artist’s Space in 1977 (to be fair, it was the thirtieth anniversary of Crimp’s important article in October magazine, a broad articulation of his argument in which he also discussed the work of Cindy Sherman, who was not included in his original exhibition).

Face-to-face once more with some of the most iconic images from the so called Pictures generation, it struck me that few moments in the history of art match the late 1970s for its wide-ranging and sustained critique of those institutional systems through which meaning is manipulated and, more importantly, produced. Certainly the Italian Futurists and various strains of Dada vigorously attacked the mechanisms of power and the conventions of representation, and articulated a radical new vision of what art and life should be. Likewise, the 1950s witnessed Jasper Johns’s and Robert Rauschenberg’s devastating assault on both the painterly gesture as an index of authenticity and originality, as well as the mythology of the abstract expressionist artist.

But the generation that came of age in the 1960s internalized its era’s incredulity towards institutional authority, artistic or otherwise, while growing up in a culture of mass consumption increasingly dominated and defined by images. It was up to this generation to employ the appropriative and quotational strategies inherited from the likes of Johns and Rauschenberg in order to investigate the insidious economy of representation in visual and consumer culture.

The Pictures generation was, like the Futurists had been seventy years earlier, a youth movement, but one that deftly understood that the most devastating way to effect a critique of a mass media system that no longer seemed to simply be representing the world around them but rather determining it, was to transact in it on its terms. In retrospect, this might be one of the most important legacies of the Pictures generation—namely their collective ability to operate within the insidious systems of meaning production in order to challenge them, and to do so without simply substituting irony for aesthetics and acumen. The work of Richard Prince, Jack Goldstein, Cindy Sherman, Robert Longo and Laurie Simmons demonstrate this rare balancing act. The art of Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst, two slightly later artists who inherited the lessons of the Pictures generation, also succeeds in finding that rare equilibrium between commenting upon and unabashedly embracing the systems of representation in contemporary culture. The current generation of artists, or at least those included in the recent Younger Than Jesus show at the New Museum in New York, seems to be in the initial stages of coming to terms with those same lessons (and increasingly muted legacy) while working in an ever more image-dominated world.

Alas, while the Pictures generation may not have opened up entire new worlds for exploration to the scale that Henry Hudson did four centuries ago this year, some 30 years ago in New York, they did demonstrate perhaps more plainly than any generation before or since that in contemporary visual culture, one must deal in the mechanisms of power in order to effect a critique of them—and that is an anniversary worth celebrating.