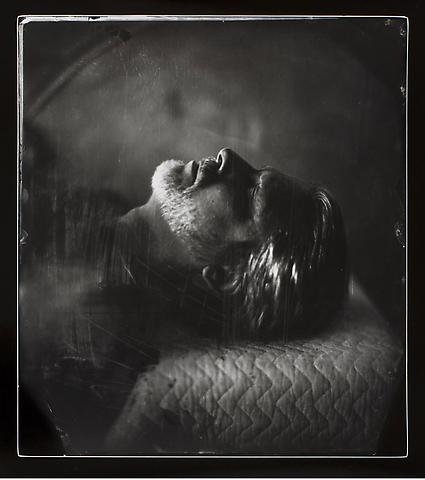

Sally Mann, "Was Ever Love," 2009. Gelatin silver print, 15 x 13 1/2 inches (38.1 x 34.3 cm), Ed. of 5. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery.

“I am not too sure whether I am dreaming or remembering, whether I have lived my life or dreamt it. Memories quite as much as dreams arouse in me the strongest feelings of the unreality and ephemerality of the world.” — Eugene Ionesco, Past Present, Present Past

There are times when Sally Mann’s photographs seem to hover in a state between private dream and shared memory, simultaneously conveying a sense of the personal and the communal within the same pictorial field. This liminal aspect is on full display in Proud Flesh, the artist’s current exhibition at Gagosian Gallery in New York. The show consists of thirty-three photographs by Mann, who has turned her photographic gaze exclusively toward her husband of four decades, Larry.

Using her signature wet-plate collodion photographic process, Mann photographed her husband over a six-year period. Shooting in close-up as he posed nude in her largely unadorned and rustic studio, the resulting images depict fragments of Larry’s naked body—and often little more—in a shallow pictorial space. The simplicity of Mann’s images is balanced by her use of the wet-plate process, which adds a warm tone to the surface of the photographs and leaves a distinctive layer of residual marks, pocks and other imperfections, all of which introduce an air of delicacy and ephemerality to these nude studies.

The outward simplicity of these photographs, however, belies a deeper complexity, for on the one hand, they are intimate studies of her husband’s naked, vulnerable body (Mann has described these images as being “like one big caress”), yet they also somehow remain familiar, accessible. What allows for these otherwise private portraits to read as familiar is, I propose, twofold.

First, Mann’s wet-plate process, and its strong associations with nineteenth-century photography, imbue her photographs of her husband’s body with a sense of a remote yet familiar past. It is as if one were regarding anonymous nineteenth-century photographic portraits in a museum or archive, where the absolute anonymity of the individuals depicted grants a certain freedom and license to the viewer’s scrutinizing gaze.

What further renders Mann’s otherwise intimate photographs readily accessible is their insistently referential, albeit elusive nature. This is to say that alongside the effects of Mann’s technical means, a sensation of vague familiarity is fostered in the photographs by the artist’s particular positioning and cropping of Larry’s naked body. The result is a series of nude studies that register as oddly familiar, referring as they do to Edward Weston’s soft-focus pictorial studies, nineteenth-century postmortem and war photography and, further, to classical tradition, specifically to the statues and statuary fragments of antiquity depicting stoic, dying figures (the titles of Mann’s photographs of her husband abound with evocative references to the antique and especially to classical myth). It is precisely these evocative associations with tradition, but yet to no one source in particular, that lends these intimate and private photographs of Mann’s husband an air of the familiar, public.

Sally Mann, "Hephaestus," 2008. Gelatin silver print, 15 x 13 1/2 inches (38.1 x 34.3 cm), Ed. of 5. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery.

In the course of walking through Proud Flesh’s three rooms, one senses that Mann’s photographs of her husband strategically allow space for two separate but equal audiences—her and her husband, and the rest of us. Filled with meaning and reference and yet also harboring something resistant to public consumption, the work oscillates from the communal to the private, as its referential relationship to antiquity and the history of photography gives way to a more private layer of meaning. It is a fluctuation between the intimate and the public—between Mann’s private “caresses” and the evocative familiarity of the glass-plate process and familiar poses—that calls to mind Roland Barthes who, in Camera Lucida, suggested that a photograph might yield a truth knowable only through a viewer’s subjective experience. This truth only exists in and through that individual’s understanding and thus beyond the surface of the image—beyond, that is, that coded surface readily legible by all other viewers.

Sally Mann has gestured to something like this dichotomy in her photography, having stated that she maintains two ways of regarding her photographic subjects when they are her loved ones: “I look with both ardor and frank, aesthetic cold appraisal. And I look with the passions of both eye and heart.” Her two regards echoing the objective and the subjective distinction Barthes desires to see in a photograph, Mann’s work fulfills the aesthetic appraisal with an abundance of historical and art historical allusion, which allow viewers to share in an elegiac meditation on photography and on the ephemerality of the human body—that proud flesh.

And yet there is also something else captured in and through Mann’s photographic gaze, something that hovers somewhere between reverie and reminiscence and bespeaks the other, more passionate look with which Mann says that she regards her subjects. There endures in her pictures of her husband something private, intimate. With regards to this project, Mann has spoken candidly about how personal and poignant it was to photograph Larry’s aging and afflicted body at this time in their lives (Larry suffers from late-onset muscular dystrophy). As allusive as they are, these compositions also remain elusive—the result of a photographic gaze that also looks with an intimacy resistant to public consumption, the pictures records of a private experience between photographer and subject, photographer and image.

Fittingly then, I conclude with Sally Mann’s own words, as perhaps only she can come close to articulating this ineffable sense of intimacy that endures in these photographs:

Larry and I began this work of exploring what it means to grow older, to let the sunshine fall voluptuously on a still-beautiful form, and to spend quiet afternoons together again. No phone, no kids, two fingers of bourbon, the smell of the ether, the two of us—still in love, still at work.

Proud Flesh remains on view until October 31.