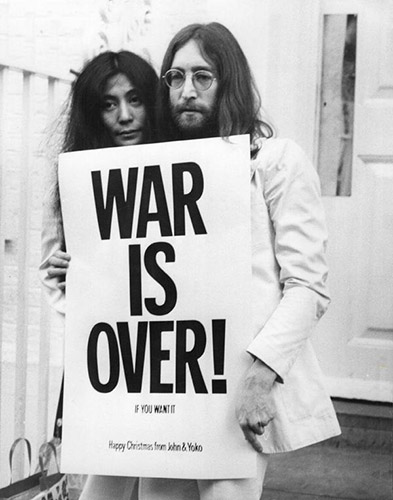

John Lennon and Yoko Ono, "War Is Over!," 1969-

I’d like to start my visit to Art21 with a close reading of a favorite artwork of mine: John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s War Is Over! slogan. This work relates to many of my current preoccupations, and will hopefully serve as a good introduction to the other subjects I will be covering in the next two weeks. Specifically, I am interested in this work’s aspirations towards presence and how, over the course of the past 40 years, this presence has been revealed to be contingent in various ways. I’ll be breaking up this post into two parts for brevity’s sake, with the first post focusing on the slogan’s original context and function in 1969-70, and the second examining its material reappearance as a postcard in 1970, 2002, and 2007 (1).

To be clear, many art practices of the 1960s and 70s aspired towards a kind of presence. For example, Michael Fried’s famous 1967 essay “Art and Objecthood” lays out the terms and stakes of an anthropomorphized presence in minimalist art. We can see these aspirations in pop art too, as Clement Greenberg implies when he discusses how presence can be achieved through both “size” (e.g. minimalism’s human scale) and “the look of non-art” (e.g. pop’s commercial design) (2). Indeed, in hindsight, it is interesting to compare minimalism’s gestalt with Andy Warhol’s Coca-Cola gestalt, in which “all the Cokes are the same, and all the Cokes are good” (3, 4). Finally, it is possible to see this aspiration in the direct linguistic address of conceptual art of the period, as well (5).

In their 1969 slogan, “War Is Over! (If You Want It) Happy Christmas from John & Yoko,” the artists approach presence through a combination of the pop advertisement and conceptual art’s linguistic address (6). This combination conflates the existential responsibility of individual choice with the consumer’s buy/not-buy binary. The slogan also plays upon the utopian longing that animates all advertising, in which a commodity promises to solve life’s problems. This blending of the sacred and the profane might strike one as unexpectedly cynical, and it is possible to further draw this out through an examination of the slogan as discourse. For this, I turn to art historian Janet Kraynak’s excellent essay, “Bruce Nauman’s Words” (7).

For Kraynak, the personal pronoun and present verb tense of the slogan’s direct address signal that we have entered what linguist Emile Benveniste calls discourse: “the subjective, lived time of language – as opposed to ‘history,’ which isolates [language] from the subject and from the ongoing rhythms of time.” As discourse, then, the slogan’s address creates a situation in which “each subsequent viewer represents another potential ‘you,’ produced at the time of encounter.” These moments are “infinitely repeatable,” creating the desired effect of eternal presence (8).

However, understanding John & Yoko’s slogan in terms of Benveniste’s discourse has unexpected implications. For if it is now possible to have the word “you” describe each subsequent viewer, the word “war” must now also describe current and subsequent conflicts. Thus, although War Is Over! was produced as an idealistic response to the Vietnam War, the slogan’s lack of a specific referent implies the eternal continuance of war, the very thing John & Yoko ostensibly want to end.

It is this paradoxical simultaneity of idealism and cynicism, agency and powerlessness, presence and contingency that elevates the work beyond propaganda. Indeed, in its contradictions, this simple slogan elegantly evokes the human condition. As John Lennon said in response to the campaign’s perceived naïveté, “We keep on with Christianity although Christ was killed, and it’s the same thing” (9).

Notes

1. These familiar postcards are just one aspect of the artists’ larger War Is Over! campaign, which has continued intermittently in various media from 1969 to the present.

2. “[Anne] Truitt’s art did flirt with the look of non-art, and her 1963 show was the first in which I noticed how this look could confer an effect of presence. That presence as achieved through size was aesthetically extraneous, I already knew. That presence as achieved through the look of non-art was likewise aesthetically extraneous I did not yet know. Truitt’s sculpture had this kind of presence but did not hide behind it. That sculpture could hide behind it – just as painting did – I found out only after repeated acquaintance with Minimal works of art: Judd’s, Morris’s, Andre’s, Steiner’s, some but all of Smithson’s, some but not all of LeWitt’s” (Clement Greenberg, Modernism with a Vengeance, pg. 255-56, quoted in Michael Fried, Art and Objecthood, pg. 152).

3. “What’s great about this country is that America started the tradition where the richest consumers buy essentially the same things as the poorest. You can be watching TV and see Coca-Cola, and you can know that the President drinks Cokes, Liz Taylor drinks Cokes, and just think, you can drink Coke, too. A Coke is a Coke and no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking. All the Cokes are the same and all the Cokes are good. Liz Taylor knows it, the President knows it, the bum knows it, and you know it” (Andy Warhol, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again).

4. Hal Foster has written specifically about the similarities between Pop and Minimalism but, for the life of me, I can’t find the article at the moment. I think it was in a catalogue from the late 80s.

5. I am thinking here more of Bruce Nauman than Joseph Kosuth.

6. A contemporaneous news article contained the following commentary from Lennon: “You see advertising is the game. We would like to make our campaign as you see the ads on TV. Every time you’d turn on the TV set, you’d see ads for peace…If anyone thinks this campaign is naïve, let them come up with something better and we’ll join it. We’re artists, entertainers and this is our way” (as quoted in the catalogue for Yoko Ono Imagine Peace at The University of Akron, 2007, pg. 23).

7. This essay is found in her collection of Nauman interviews, Please Pay Attention Please: Bruce Nauman’s Words. See pg. 27-28.

8. Kraynak’s full text reads: “Collectively, the personal pronouns and the present verb tense belong to what [Emile] Benveniste calls ‘discourse’ –the subjective, lived time of language– as opposed to ‘history,’ which isolates it from the subject and from the ongoing rhythms of time.” “We shall define historical narration as the mode of utterance that excludes every ‘autobiographical’ linguistic form,” Benveniste writes. “The historian will never say je or tu or maintenant, because he will never make use of the formal apparatus of discourse, which resides primarily in the relationship of the persons je: tu.”

Accordingly, the dialogue spoken in [Nauman’s] Good Boy Bad Boy is based upon the intersubjective relationship of the linguistic “I” and “you.” Furthermore, the speakers, each occupying a separate monitor, direct their messages outward, not just to each other but implicitly to the viewer, who also assumes the place of the subject “you” in the exchange. Each subsequent viewer, therefore, represents another potential “you,” produced at the time of encounter. Similarly, in First Poem Piece, the word “here” suggests not a fixed place and time, but the situation in which the beholder encounters it. Every new interaction with “now,” for example, results in another present and with “we” another group of subjects. Such moments are infinitely repeatable. As in [philosopher of language J.L. Austin’s] performative – which, to recall Derrida’s observation, operates within a structure of “general iterability” – in Benveniste’s “discourse,” presence is eternal.

9. See (6).