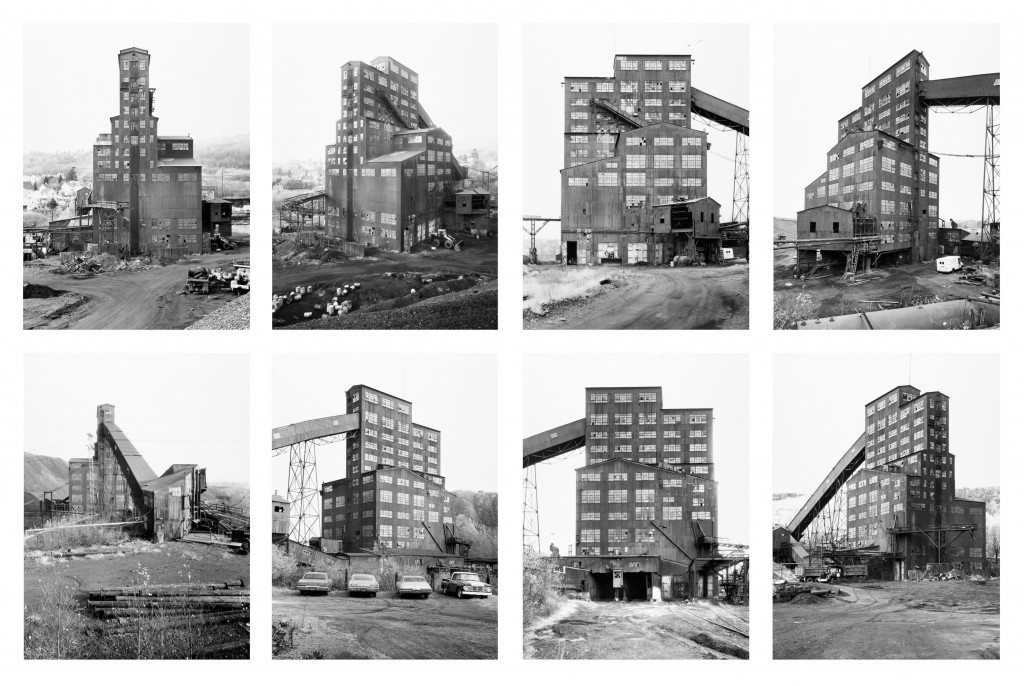

Bernd and Hilla Becher. "Harry E. Colliery Coal Breaker, Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania," 1974. 8 Gelatin Silver Prints, 16 x 12 in. each. Courtesy Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

“Life is boring,” said Matthew Coolidge, talking about how most of us live in the uneventful “periods between the monuments.” Coolidge, the director of the Center for Land Use Interpretation, an institute that explores often-overlooked landscapes, has made a career out of documenting everything “boring” and in-between—helipads, hidden oil wells, mile markers. He spoke at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art on Saturday as part of a day-long symposium. Called “What’s at Stake? New Topographics and the Man-Altered Landscape,” the symposium accompanied LACMA’s current exhibition of neutral, mostly black-and-white landscape photographs (though every landscape is marked by man-made structures) from the 1970s. These photographs render the boring parts of the US topography in a way that seems to presciently foreshadow today’s general wariness toward monumentality and obsession with sustainability.

Joe Deal, "Untitled View (Albuquerque)," Gelatin Silver Print, 1974. Courtesy George Eastman House.

LACMA’s New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape is actually the restaging of an earlier exhibition by the same name. The first New Topographics appeared at the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York, in 1975. Like its restaging, it included images by Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Joe Deal, Frank Gohlke, Nicholas Nixon, John Schott, Stephen Shore, and Henry Wessel, Jr. None of these photographers aggrandized their geographical subjects. Instead, their intentionally composed photographs were coolly barren in ways that almost seemed radical.

"New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape," Catalogue. Courtesy George Eastman House.

Though not well attended, the 1975 New Topographics exhibition became an art world phenomenon. “Everyone knew everything about it but no one had ever seen it,” said Eastman House curator Alison Nordstrom. “I think it gave [photographers] permission to be more experimental. It gave people permission to be less concerned with the beautiful and more concerned with the true.” Certainly, the photographers in the show took truth seriously. Images like Frank Gohlke’s Landscape, Los Angeles, in which a telephone pole and a bush are the image’s motionless protagonists, or Robert Adams’s serial images of modest tract homes, in which unassuming structures stand on otherwise rural landscapes, seemed to be precious scientific documents. Through their deference to the sprawling natural terrain, they also seemed to suggest that the land, not the man-made structures imposed on it, would eventually have the last say.

LACMA’s exhibition opened two weeks ago and it does its best to maintain the cool-headed quality of the first exhibition. The museum has also made an impressive effort to unpack the current relevance of New Topographics, inviting artists like Cathy Opie and Shannon Ebner to lead exhibition walkthroughs and hosting Saturday’s symposium—cultural critic Norman Klein nimbly expounded upon the orange groves and oil wells that populate Los Angeles’s legacy; curator Phillip Kaiser talked about land art’s place (or non-place) in the museum; and architecture writer Christopher Hawthorne discussed the looming fear that the land will eventually take over everything we make.

Henry Wessel, Jr., "Buena Vista, Colorado," 1973. Gelatin silver print, 11x14 in. Courtesy George Eastman House Museum of Photography and Film.

Among all of Saturday’s panelists, however, it was curator and theorist Douglas Crimp who gave the most compelling argument for repeating the past. He gave as an example the 1965 Andy Warhol cinematic parody of the Cuban revolution, The Life of Juanita Castro, noting that the part of Juanita Castro was originally written for performance artist Mario Montez. Montez refused the part in 1965, but just a week ago at a Berlin festival that ran from October 28-November 1, Montez appeared in a restaged version of Life of Juanita. Feeling that Cuban-US relations had developed to such a point that the play was especially relevant, Montez agreed to make the intended Life of Juanita and an artwork that debuted over forty years ago was finally realized, for the first time, in its intended form.

Crimp’s story nicely served as a metaphor for New Topographics. A show that people didn’t fully understand until after it was over, certain aspects of New Topographics may be understood in ways they weren’t understood before, now that we’re primed to look more carefully at how we interact with land.