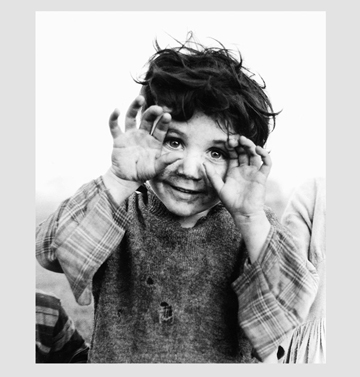

Alen MacWeeney, "Bernie, Cherry Orchard," circa 1976. Gelatin silver print, dimensions variable. Courtesy www.alenmacweeney.com.

It hardly seems fair that in today’s world of the point-and-shoot dominated landscape, where a common tourist can not only take a professional photograph but adequately circulate it via the internet too, that we are seeing an influx of historic photography in the art market. Yes, the images are certainly of interest, but haven’t we redefined our relationship with the image in a daily existence of friends tagging us in Facebook shots? What in history is so contemporary? How are New York and California art dealers and auction houses, such as Phillips de Pury, working up the nerve to charge thousands of dollars for a vintage photograph unearthed from the dusty photography studio? And speaking of the studio, where does the photographer as the artist fit in all of this? Where does craft and precision? I don’t know that I have all the answers, but I do know that documentary photography looks darn good on contemporary white walls. It seems this may be the new place for it, for better or for worse, as bulky photography books make their comeback in all their design glory and new standards for print quality.

Alen MacWeeney, "Willie Donoghue and Children," circa 1976. Gelatin silver print, dimensions variable. Courtesy www.alenmacweeney.com.

Not too long ago, it seems, I was Assistant Director of the Steven Kasher Gallery in Chelsea and had received a crash course on the true marketability and value of the photographs many a contemporary collector may take for impostors in the art world. And, I have to say, much like the art world in general, value is a questionable entity, as it is assigned by a handful of pioneers willing to be the first to put historical documentation up on white walls and call it art. Oh, and of course attach the appropriate price tag. What else could explain the booming sales of mugshots from the 40s and 50s? Yes, they are available on eBay for fraction of the gallery cost, but the juicy ones with notes on crimes such as “loitering” and “looking suspicious” and the ones with the wildest hairdos will cost you. Take a look at more here. And should we speak of the collectors of photography as art, who seem to feed their collections with images of high value and fetishized subject matters? It would be easy to pick out, for instance, Diane Arbus as being on the other side of this deal (the photographer living as artist and not thinking much of it). Arbus, whose photography and ephemera has been widely exhibited in the art world and sold (see, again, Phillips de Pury last year) for incredible prices.

Well, lets just say it would be nice if any of the photographers still alive received the accolades. The thing is, photographers don’t get rich unless they go commercial. Not today. Is it because the market is just not ready to accept the value of a moment captured soulfully and then printed so skillfully that no flaw in exposure, paper, grain, or spotting can be detected as fine art? Is it the fact that we are convinced that we are all just as good, with the same means for travel and documentation of our world? Or is it that we like things a bit more painterly?

Page spread from "Least Wanted: A Century of American Mugshots" by Mark Michaelson & Steven Kasher. Steidl & Partners, 2006.

All I know is that the value of a moment in time can truly be priceless, as is its context within history and culture. Alen MacWeeney is one artist I’ve met in my brush with contemporary gallerisms that touched me with his work in a very real way. Not only because his images are so evocative, where a people are portrayed with dignity and vulnerability and, ultimately, all of their humanity intact, but because he is a purist in a good way. He is a master printer with such regard for perfection that his prints speak for themselves. Not a speck of dust, not a single sign of overexposure. Even the black-and-white shots of the Irish Travelers (derogatively known as the tinkers) from the 70s are so alive, for lack of a better word, that they actively play with the viewer. The young and the old are equally playful and sorrowful; their humanity contagious and real in a way to which not every lens connects. So what is the value of a photographic print? If you ask me, it is very much outside of the market phenomenon, but is rather serious nonetheless.