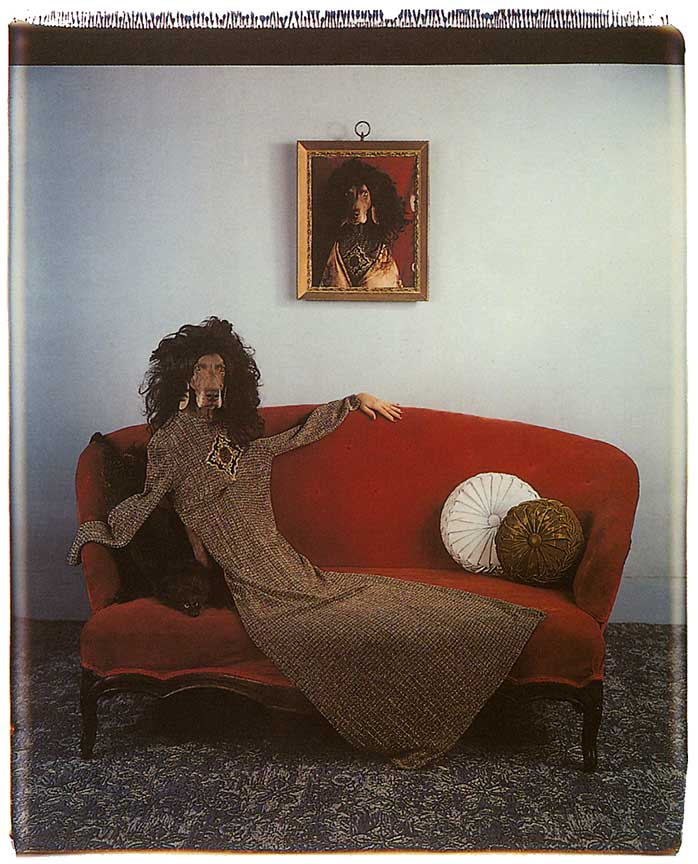

William Wegman,"Stepmother," 1992. Color Polaroid, 24 x 20 inches. © 2005 William Wegman, courtesy the Artist.

In a recent interview in the New Yorker, artist-of-the-moment Urs Fischer said something about how art and memory work together. I can’t remember the exact quote. It was something about the experience of art not being confined to the present-tense experience of being in a gallery, looking at a thing. Part of art’s test is in its retention in the mind, how it returns and why: The Physical Possibility of Art in the Mind of Someone Living, maybe. Since reading that, I have been attempting to reconstitute recently-seen works of art in my head (try it! it’s fun) and found that I can only properly recall – as in, can mentally reconstruct pretty accurately, could maybe draw — five works at most from the John Baldessari show at Tate Modern (all of those in the first three rooms), ten at the most from the Ed Ruscha show at the Hayward (all of those in the last two rooms), and one from the Damien Hirst show at the Wallace Collection (just before I considered hurling myself down their marble staircase).

Looking even further back this year, the things that have stubbornly refused to shift are a bit of a mixed bag: Roni Horn’s gold sheets for Felix Gonzales-Torres at Tate Modern (the sun in a certain place, so a honeyish glow lit up the floorboards), a Fred Sandback rope piece at the Hayward, stanchioned off with more rope (which I did an “art laugh” at: “pfffnf”), Charles Ray’s boy with frog in Venice, and his (Charles Ray’s) wobbling wire at Frieze. It’s a similar activity to trying to remember parts of a novel you read, even after you’ve just read it: I can’t remember most of Anna Karenina, for example, except for a line about fish (which is my favorite part of any novel, but it’s still a throwaway line in a 600-page behemoth).

Leo Tolstoy (fish not pictured)

Why these things have stuck and others haven’t is really down to the quality of experience, which is made up of a myriad of infinitesimal contributing factors, congruence of mood and temperature and well-being, and abeyance of hunger or tiredness or boredom, who you’re with and whether they owe you money or vice-versa. What these questions probably lead to, apart from several psychology dissertations, is one of the significant questions for educators working with art (especially with contemporary art) – well, for anyone, really: what’s the quality of our experiences with art, and how can these be improved, given so many of them slip out of mind?

The question at the heart of this is maybe: do we need to see original art to have a chance of getting it? Not always. In personal experience, I’ve taught distance learning classes to students via video link-up using color reproductions of works of art that have been as successful (in terms of quality of conversation and active participation of students) as anything done in front of original works of art. It’s preferable that students access original works of art directly, of course, especially when dealing with pre-twentieth century works, where the notion of reproduction (excluding prints and drawings) isn’t implied or understood in the work itself. Although, again, the quality of the experience is the main thing and can often be had via a reproduction, too.

To take one celebrated example of this, Francis Bacon claimed never to have seen the painting by Velazquez (the Innocent X portrait) he’d so tenaciously interpreted in his own work, despite having had the opportunity to do so when in Rome in the 1950s. His excuses for not having seen it varied according to how much champagne he’d had for breakfast, but there’s no doubt that his experience of the work as image – if not as object – constitute one of the most profound periods of attention paid to one artist by another in the history of art.

Francis Bacon and William Burroughs

Inevitably, it all comes down to the quality of reproduction, and if that reproduction comes close to capturing the real object’s presence. But given the sometimes willfully ephemeral nature of some art made after 1950 – from once-only performances to art made in remote locations to deliberately fragile, snappable materials – how much can we say that our experiences of those works are authentic ones? In other words, can the kind of art that only exists in reproduction – the kind not prefixed by, “well, it’d be better to see the real thing, but since we’re still in orbit we’ll have to make do with this mousemat of Starry Night” – be discussed without caveats?

I’d suggest that it’s certainly desirable that (say) the work of Robert Smithson is discussed in schools, but how effective can a discussion of Spiral Jetty be without a direct experience of what is (so I’m told; I’ve been very busy) a highly physical, meteorologically sensitive and infinitely various work of art? Is the interest in the primacy of interaction with the physical object disadvantaging not just students but also the legacies of certain artists, and does this mean that art teaching is subject to the (often dubious) whims of collectors and curators?

Fischer’s point (I may be misremembering, but bear with me) – that an interaction with a work of art is something that unfolds slowly in the mind over time; that the interaction, the “art moment,” is still happening when you remember the work, that I’m still ‘”reading” Anna Karenina when I remember the line about the fish – has implications for the classroom. We seek to engender high quality experiences for students with all the means at our disposal. Those experiences aren’t confined to the classroom, nor to the duration of the school day, nor (we hope) to the duration of the school year. Yet so much contemporary art is dependent upon specific context, limited duration, and paucity of means that we risk depriving it of the oxygen it needs to live in the mind, its home.

A "Mexican Walking Fish" (Axolotl)