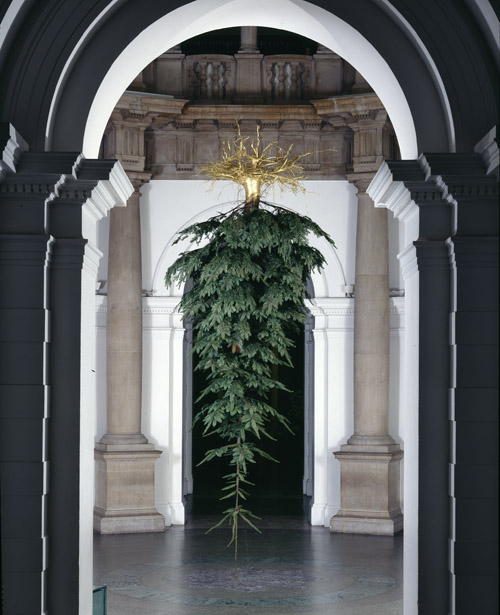

Shirazeh Houshiary's 1993 Tate Christmas Tree

Tate Britain has just unveiled its 22nd annual Christmas Tree, designed, as usual, by a contemporary British artist. The Christmas Tree tradition at the Tate started in 1988 with Bill Woodrow’s cardboard box decorations, and has retained its position of locus for skepticism ever since. Michael Landy’s infamous tree – dumped in a bright-red bin amongst crushed beer cans and discarded packaging – looked, in 1997 (the year of Sensation at the Royal Academy), like a final, sarcastic postscript to an annus horribilis for the bastions of traditional art. The current tree, by Tacita Dean, uses a pine tree hung with beeswax candles, lit at 4pm as the sun sets, which burn out by 6, when the gallery closes. It looks like a normal Christmas tree, in other words—a “delightful, almost magical sight,” according to Martin Gayford at Bloomberg. There’s no mistaking the undertone of relief in his words.

What’s changed? Minor though the tree might seem, both institutionally (it’s generally seen as a bit of seasonal frippery on the part of the Tate) and artistically (it’s often an opportunity for artists to do a bit of festive self-mockery), there’s something here of a piece with the choice of Richard Wright as this year’s Turner Prize winner: a shift of institutional focus, maybe. Positioned in the hexagonal entrance hall in Tate Britain, a kind of public hub where exhibition tickets are purchased and directions sought, the Christmas tree is a tone-setter. Dean’s tree acts as a kind of preface, pointing into quietness rather than the sometimes predictable brashness of earlier years. Praising the tree in The Guardian, Jonathan Jones describes Dean’s work as “effortlessly going against any fashion you can think of.” I’m not sure that Dean’s elegiac analogue works (which I’m a fan of) are really so different from works by artists of a similar bent, like Rodney Graham or Rosalind Nashashibi, but never mind. Jones correctly identifies a change of tack, at least in terms of the Tate’s patronage of contemporary art.

That sense of relief – that contemporary British artists had finally “settled down,” that the Tate had stopped being silly, like a 4-year-old falling asleep after a sugar rush – characterized the coverage of the Turner Prize this year. “Publicity-grabbing stunts are refreshingly absent,” claimed Ben Hoyle in The Times, forgetting that any such “publicity stunts” are overwhelmingly orchestrated outside of the shortlist by feeble self-styled mavericks the Stuckists, hopped up on the gleeful idiocy of the tabloid press. “This year’s nominees,” Hoyle continues, “all paint, draw, or make objects that are recognisably works of art.” In actual fact, this year’s shortlist no more or less troubles the definition of art than any previous one has – apart from its continued snubbing of women artists as winners, of course. There have been only three female winners since 1984, an extraordinary situation rarely mentioned in coverage of the prize. Maybe they don’t notice.

The traditional cry of the contemporary art skeptic – that painting is generally overlooked – is wrongheaded, too. In the Daily Telegraph, Stephen Adams claims, lazily, that “painting has made a surprising comeback…after years of being neglected.” Actually, most years (see the complete list here) have featured painters (or, at least, artists who paint), and several painters have won the prize – Malcolm Morley, Howard Hodgkin, Chris Ofili, Keith Tyson, and Tomma Abts – not that the practice of painting is any indication of a dedication to art-historical tradition, or that painting is by necessity a non-conceptual practice (just ask Poussin). And Richard Wright’s victory – his installation showed a huge, intricate gold wall drawing – is not the return to traditional values, as some commentators have read it. “Reversing almost all expectations,” thus Louise Jury in the Evening Standard, “Wright draws every day, basing his wall paintings on thousands of these drawings.” Crikey!

Richard Wright at Tate Britain

The principal problem with the Turner Prize shortlist is surely its implicit proposal – or, at least, that extrapolated by the press – that it represents the breadth of approaches that contemporary art encompasses. The inclusion this year of some art dependent upon traditional skills of drawing and printmaking does not represent a sea change in contemporary art. Last year’s disgruntled surprise at the lack of controversy in the shortlist – a position that has retroactively reduced Chris Ofili’s gorgeous and intricate work to “elephant dung paintings” and Mark Leckey’s esoteric and erudite film work to “a video about cartoon characters” (according to Rachel Helyer Donaldson at The First Post) – has given way to an across-the-board sense that Young British Art has finally grown up. The vitriolic press coverage of Damien Hirst’s paintings hung at the Wallace Collection had an undertone of relief, too – finally (the implication was), something we can actually understand: paintings! And yet there’s a reluctance to let go of the YBA good old days, whatever the press claims; no show of conventional figurative paintings or bronze leopards is going to shift papers. Tom Lubbock‘s review of the Hirst show, in the Independent, summarizes that dependency as follows:

A few quick questions. 1. Are these new paintings, painted by Damien Hirst himself, any good? No, not at all, they are not worth looking at. 2. So why are you writing about them at such length? Because he is very famous. 3. And why has the Wallace Collection decided to exhibit them? Because he is very famous. 4. And why did Damien Hirst even paint them in the first place? Because he is very famous.

Happy Holidays!