This is part two of my interview with Esopus editor, Tod Lippy (click here for part one). In addition to the interview, readers may also want to check out “The Assembled Picture Library of NYC”, a collaborative exhibition and workspace environment organized by artists Robin Cameron and Jason Polan. The exhibition will provide free and open access to hundreds of images from the collections of Cameron and Polan. Visitors are invited to come in during gallery hours (Mon/Tue/Thu from 12-5pm) and use these images—which include manuscripts, advertisements, prints, original drawings, and more—as raw material for their own artworks, which will be displayed on the walls of Esopus Space for the length of the exhibition. Polan and Cameron will also create a book featuring visitors’ artworks, The Assembled Picture Library of New York Book, that will be available at the closing reception on March 18th.

Joe Fusaro: Esopus is a tremendous resource on many levels. Can you talk about the magazine’s relationship with educators? Have you had experience with teachers using the magazine in their classrooms, and if so, how?

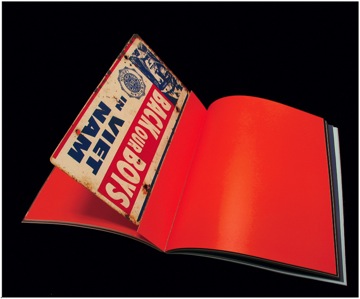

Tod Lippy: I know that Esopus has been used as an educational tool by a number of our subscribers who happen to be teachers. One issue in particular has been especially popular in that regard: Esopus 6: Process, which featured evidence of the working methods of a number of different creative people — work journals from the late Christopher Isherwood relating to the writing of A Single Man; a photographic documentation of the making of a dry-point etching by the artist Sylvia Plimack Mangold, the comic Demetri Martin’s joke diaries, and even a paper model (which our readers could build from pre-cut forms included in the magazine) of a dodecahedron offered by the mathematician John Conway, who always employs model-building when working on a new theorem. But every issue of the magazine features content — such as our “Modern Artifacts” series produced in conjunction with the Museum of Modern Art Archives — that offers learning experiences for readers of all ages.

Since the editorial tone of the magazine is deliberately neutral — we try to avoid critical jargon that might be off-putting to more general readers — and since the artists’ projects in the magazine rarely have any introductions or explanations preceding them, I guess one could argue that the magazine is actually neglecting the opportunity to teach its readers about the meaning of contemporary art (much of which, of course, can feel oblique to people lacking art degrees). But to tell you the truth I think the experience readers have with the work in the magazine, which they are forced to approach on their — and its — own terms, may end up being a deeper one in many cases.

Incidentally, I think that perhaps one of the best things Esopus has to offer younger readers, particularly in this era of publishing, is an essentially commercial-free environment. I’ve spoken at a number of high schools and colleges about the magazine, and when I deliver lectures I bring along a Powerpoint presentation during which I ask for a show of hands from the audience as I project photos of spreads from current magazines. I ask them to raise their right hands when they recognize an ad, and their left hands when they see editorial content. I start with obvious choices — a Nike advertisement, a page from The Talk of the Town in The New Yorker — but it’s amazing how quickly confusion sets in when I show them an “advertorial,” or a paid-for “special supplement” that apes the look and feel of the particular magazine. Advertising is so pervasive in every nook and cranny of our culture that it really isn’t noticed anymore, and I think that’s problematic, especially for young people who should know when they are being sold something.

JF: Have you been under pressure at certain points to include advertising for one reason or another?

TL: Not really, no. The only entity in the magazine world that typically applies pressure regarding advertising is the publisher, which in this case is the Esopus Foundation. And the fact of the matter is that very few smaller circulation art magazines make any kind of significant revenue from ad sales anyway. So at this point it wouldn’t really make financial sense to open up the magazine to advertising.

JF: I have asked students to draw similarities between ideas and artists in specific issues or perhaps create lists of traditional and non-traditional media used to create the work in a given issue. Do you have any particular advice for those who might want to teach with the magazine or get more involved with Esopus outside of the magazine itself?

TL: I think (at least I hope) the magazine offers students and teachers a way to access the efforts of creative people in a very direct manner (as discussed earlier, without critical or commercial interruption), which ideally opens them up to different ways of looking at the world. I also believe that because Esopus is so devoted to its materiality, it raises some interesting questions about why printed matter can still offer a unique experience to readers that can never be replicated on the internet. It’s not that it’s necessarily better or worse than the experience of reading or viewing work online, but it is probably worthwhile to consider exploring the meaning of that very physical relationship with younger people, who have much less of a “history” with it.

As for going outside of the magazine, we now have an exhibition and performance venue in Greenwich Village called Esopus Space and we’ve been thrilled to see a number of students showing up for both exhibitions and for our series of lectures, screenings, concerts, and the like. One plan we hope to implement in the near future is to institute a series of workshops for high school students in the area, who will be invited to visit the space, get a tour of whichever exhibition is up at that time, and also learn more about Esopus and the magazine publishing in general.