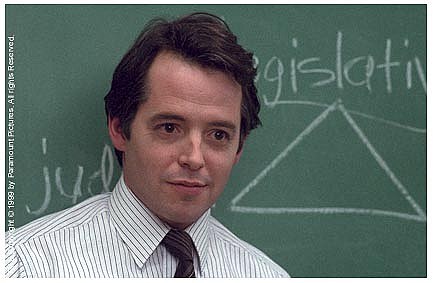

Matthew Broderick in "Election"

“There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written or badly written. That is all.”

— Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray

“What’s the difference between morals and ethics anyway? Anyone?”

— Matthew Broderick, Election

If there’s a tipping point in the minds of those casually interested in contemporary art, it’s almost always on moral or ethical grounds. “He/she did what to a dog/sold what for a billion dollars/did what to a dead cow/did what to a crucifix??” your amazed friend asks, and suddenly all credibility is leached from the subject. You’re embarrassed; you get your coat. Later on, you blog resentfully at your friend’s apparent narrow-mindedness (and defriend him: take that!). Art’s leapfrogging of moral and ethical niceties is a Romantic hangover that once was noble and exciting – Courbet, Baudelaire, 2 Live Crew – and now reeks of ghettoized cliché. It’s the thing people don’t like about contemporary art. And the less contemporary art complies with “real world” ethical and moral structures, the less it is of the “real world.” And yet this is what we value in art (in its current late-Romantic state): its ability to discuss the things avoided in the mainstream imagination. To ask difficult questions. This is the double bind of contemporary art’s relationship with ethics. Its purported snubbing of conventional (Judeo-Christian) ethics both allows it to discuss the undiscussable and removes it from the discussion.

When Santiago Sierra created a gas chamber in Pulheim, Germany, in 2006 – filling a synagogue with exhaust fumes from six parked cars, accessible only for five minutes to visitors wearing gas masks – he whipped up a predictable furore. That most critics of the work (including me) never experienced the work doesn’t really matter: that it raised ethical questions does. This is the unfortunate situation contemporary art gets itself into when tackling sensitive ethical or moral issues: the media storm generated by the work is the work, and the original piece itself is drowned out by the buzz of voices. Art of this kind negates its own irrefutable trump card, its visual singularity. The problem is that visual art’s status as chief cultural question-raiser has been gradually usurped, not just by other more immediate cultural products, like cinema or TV (Inglourious Basterds treats the commercialization of the Holocaust in a far more successful – read, “widely seen” and “aesthetically enjoyable” – way), but by the multiplicity of dissenting voices made possible by the advent of the Internet. Why bother jetting in an internationally recognized artist at spectacular fiscal and environmental cost to raise ethical questions when you can do so yourself, sitting at home, with Doritos crumbs all down your shirt?

Jeff Koons, "Art Magazine Ads (Artforum)," lithograph, 1988. Courtesy the artist.

Or take Andrea Fraser’s 2003 performance/video Untitled, in which she had sex with a collector for $20,000. The video – which is the entire “performance” shot from a CCTV camera above the bed in a posh hotel – does the rounds every so often, and featured in Tate Modern’s Pop Life show last year, a show which itself raised, inadvertently or not, certain ethical issues. Fraser’s video is, of course, about ethics. Neither of the parties involved were knowingly exploited, unlike the majority of paid-for sexual encounters (but those don’t raise questions, do they?). Fraser’s work, like Sierra’s, is made with an eye to its afterlife in text; it doesn’t need to be seen to be known. In the Tate’s Pop Life catalogue, Untitled is described thusly:

Fraser challenges the idea of access as a literalised pun – she is “in bed with the collector”…[she] brings our attention to her deliberate reversal of conventional power relationships by exaggerating the strength of her own position…[she] radically mak[es] visible attitudes of complicity…[and] problematise[s] the ideal of artistic autonomy upon which the art market hinges…

“Problematise,” “brings attention to,” “radical” — this is the sound of art talking to itself. Contemporary art such as Fraser’s and Sierra’s seeks to absolve itself from ethical responsibility by preemptively defining its own ethical framework. The dead language of contemporary art becomes the means by which this is achieved. A work of art might perform in a way that in “the real world” would be considered unethical, immoral, or criminal, but within the nested discourse of the academic write-up, it’s not unethical; it’s raising questions about ethics. And in order to do so, art must think of itself as existing outside of – perhaps even above – the moral framework that structures ethical decisions in other cultural arenas.

Joseph Beuys's "Action Piece," 26-6 February 1972; presented as part of seven exhibitions held at the Tate Gallery 24 Feburary - 23 March 1972. © Tate Archive Photographic Collection.

You’re not really supposed to discuss moral and ethical matters around contemporary art, though. Disdain for moral squares is so entrenched that those questioning the morality of works of art are jeered at from the ramparts as backwards or unsophisticated. Express discomfort at Sierra’s synagogue or Fraser’s fornication or at a range of diverse “question-raising” activities (Andres Serrano, Damien Hirst, the Chapman brothers, etc.), and your contemporary art membership card is permanently revoked. They tear it up in front of your face and leave your headshot with the Art Basel bouncers. It’s a measure of contemporary art’s insecurity that discussions of ethical issues are relegated to the sidelines. No amount of furious Rachmaninovian typing about the New Museum’s show of Dakis Joannou’s private collection, for instance, was ever going to slow its tank-like inexorable forward motion. It’s worth reading some of (not all of; it’s time you can never get back) the wildly disproportionate back-and-forth on that show by New York art bloggers (it’s barely known about outside of New York, by the way). Ethical in-fighting looks comically pedantic to art world outsiders, and it’s easy to forget there’s any art actually involved. And isn’t that what we ought to discuss — the possible ethical dimensions of a post-Romantic art? Anyone?

Bueller?