Museums have been disposing of objects since they began acquiring them. The first documented “deaccessioning” may have involved some of the decayed remains of a Dodo bird, destroyed at the order of a keeper of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History in 1775. Fortunately, the individual assigned to the task chose to retain the Dodo’s head and a foot, which were in presentable condition. Without his disobedience, we would lack DNA evidence of the extinct creature that continues to be of use in contemporary research.

Art museums are places of particular interest for those who follow deaccessioning, because the affected works tend to be, like the last surviving Dodo, unique in at least some respects. Even multiples like etchings and engravings have subtle distinctions in quality and condition.

Disobedience in the act of deaccessioning today is as rampant as it was with regard to the 18th-century example of the Dodo—except that the untoward behavior of our time is not in service of preserving and protecting collections, but in service of monetizing them.

In 2007, the Indianapolis Museum of Art embarked on a considered campaign to undertake deaccessioning of those works among its 54,000 object collection that were considered insufficiently connected to the IMA’s mission. There were six possible rationales for deaccessioning articulated in the February 2008 revision of the Museum’s Collections Management policy (emphasis mine):

- Objects that are not appropriate for the permanent, study or Lilly House collections or are not consistent with the goals of the Museum.

- Objects that are determined to be below the level of quality necessary to advance the Museum’s mission or possess little potential for research, scholarship or educational purposes.

- Objects that have been forged or misrepresented by the seller. A forgery is defined as a work that was intentionally made or sold for the purpose of defrauding buyers, or that has been altered in any way toward the same end. For ethnographic art, this definition also includes objects not made or used in their traditional contexts. Forgeries do not include studio work, copies, imitations, and similar works made without deceitful intent and sold in good faith by a reputable dealer. Objects misrepresented by the seller include forgeries and objects with falsified provenance.

- Duplicate and redundant objects. An example would be two prints of the same state. The Museum shall retain the superior example. Condition and source shall also be considered. Redundant works include objects that are either duplicates, or similar variants, such as slightly different states of the same print. They also include works closely related in subject and style by the same artist or school but varying in quality, condition and interest. In such instances, the Museum shall retain the superior example.

- Objects damaged or deteriorated beyond reasonable repair.

- Items for which the Museum is not able to provide proper storage or care.

Notably absent from the Museum’s rationales for deaccessioning are two motives that other museums have invoked, but which are not believed to be advisable at the IMA.

The first criterion that has led to raging controversies at other institutions is the sale of works for a purpose other than acquiring new works—up to and including patching holes in the roof or holes in the operating budget. This criterion is unacceptable to members of the Association of Art Museum Directors, who believe that the use of accessioned objects in this way is a bad idea for a host of reasons, which are specified by AAMD on its website.

The second of these inadvisable motives would be selling one or more fine objects to acquire a work that is considered to be a yet finer work by another artist—or trading up, not from a lesser work, but from one avowedly fine work or works to acquire another. It is the opinion of the current IMA administration that such judgments are potentially very problematic, resting as they do not on a third-party adjudication that a work is of lesser value, which we undertake in the case of our second deaccessioning criterion (“below the level of quality necessary to advance the museum’s mission”), but on the conviction that today’s taste and preference trumps yesterday’s.

While this second motive is very difficult to distinguish from a judgment about the quality of a work of art, it is IMA’s opinion that “trading up” runs the very real risk of being proven wrong by our successors and, if carried to an extreme, would lead to an indefensible use of the permanent collection as an impermanent resource to satisfy the shifting tastes of curators and directors from one generation to the next.

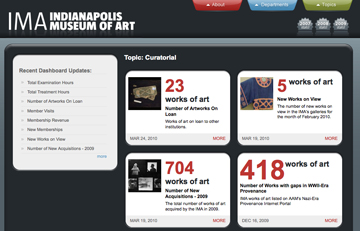

I remain surprised by the suggestion that our museum’s determination to be completely transparent about our motives for and gains from deaccessioning is anything other than an obvious obligation. My colleagues in other leading art museums conceded the point in AAMD’s 2007 position paper, “Art Museums and the Practice of Deaccessioning,” but to date, I know of no other art museum planning to present a complete, illustrated, and searchable database of the works out their way out the door. I would hope that as a field we could agree that this is a collective obligation before lawmakers decide that it is and arrive at approaches that are at odds with our non-profit, educational mandate.

Maxwell L. Anderson is the Melvin & Bren Simon Director and CEO of the Indianapolis Museum of Art.