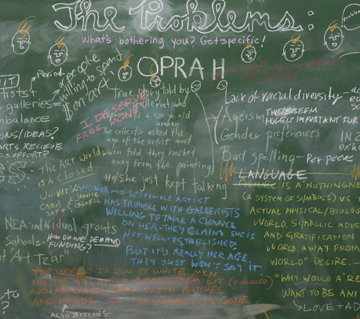

View of the chalkboards that covered the walls of the Winkleman Gallery during the #class exhibition. Visitors were welcome to write or draw on the boards. (Photo courtesy of Jennifer Dalton)

Last week, the #class exhibition at the Winkleman Gallery closed after a month of functioning as New York’s laboratory for art world gripes, think tank for new ideas, and classroom full of possibilities. Co-curated by Jennifer Dalton and William Powhida, the show welcomed a long list of guests to present events, actions, discussions, lectures, and everything in between, for an audience that was both real and virtual (all the events were video streamed live on Ustream, which was also embedded on the exhibition blog).

It felt like half the city’s art world took part in this mediated meeting of the minds. I even contributed a small project that welcomed people to submit ballots filled out with information about who in the art world owes them money (I received dozens of submissions).

After #class started, what already felt like a sprawling project began to feel all-consuming, as you could participate in person or online. Simultaneous conversations on Facebook, Twitter, and some art blogs endlessly chattered about the events and the perceived successes and failures of #class. Yet as the exhibition progressed, I really found myself more and more interested in what Dalton had to say about the project and its evolving accomplishments. Unlike Powhida, Dalton is much more reserved and not as quick to express opinions or challenge people publicly over ideas. She is an accomplished conceptual artist and her work feels coolly objective and measured in its response to the world. I wanted to understand what the significance of #class was for her and asked her to speak to me over email. She agreed.

This online conversation took place throughout the last two weeks of #class and represents some of her evolving ideas about the exhibition.

* * *

Hrag Vartanian: What role do you think ethics should and/or does play in the art world? If any.

Jennifer Dalton: I think ethics should play a role in every area of human activity; the art world is not separate in any meaningful way. I think we should always try to do what is right, honest, helpful and productive, and strive to act in a way that we wish everyone else would act. It is not always achievable, but that’s the goal.

Co-curators William Powhida and Jennifer Dalton as depicted in An Xiao's "Photoglam" series that was taken during the opening night of #class. (Photo courtesy of the artist)

HV: Is that your goal? Either way, do you think it helps you succeed or holds you back?

JD: Yes, it’s my goal. Sometimes I think it helps me succeed and sometimes I think it holds me back. I think it has helped me more than it has hurt me, both because I am willing to work really hard and because I do my best not to make anyone else’s life more difficult. People don’t like to work with you when you make their life difficult. Ed Winkleman’s an exception, bless him.

HV: Now, how does #class fit into the recent debate about ethics in the art world? It seems as though it emerged from a real sense that the art world may have partly lost its way and was starting to have trouble distinguishing what was right and wrong.

JD: In part, the #class project definitely evolved from a feeling that the art world is not governed by a normal sense of right and wrong. Some of our particular bones to pick were that artists cannot count on getting paid for sales by their galleries (many of which are run by people who have no business running a business), that the finances of contemporary museums seem to be forcing them toward inane blockbusters and/or exhibitions of ethically challenged conception, that the most “important” art events have become absurd parodies of spectacles, and that what used to be multiple avenues of artistic “success” have winnowed down into the single definition of conspicuous validation by the art market.

Further inspiration behind #class was also a queasiness that William and I identified in ourselves about participating, even honestly and in good faith, in this strange marketplace. It’s uncomfortable to sell work (or attempt to sell work!) that is priced at nearly your own yearly income. It means that no one in your own circumstances can afford to buy your work, which feels alienating. We don’t know if there is a better way to support art and artists so, among many other things, #class is about trying to figure that out.

A view of the end of Man Bartlett's "24hr" performance at #class, as seen on the video stream.

HV: Some people conflate ethics with morality. What is their relation?

JD: Well, you are giving me an open book test here, since I literally have the Internet at my fingertips as I answer this question. But I will try to answer first without confirming what I think, which is that ethics are socially-organized morality. But it’s common to use them interchangeably, as I’m sure I have, which is probably why you’re asking this. Now I’m going to go look it up and see how badly I mangled it.

HV: What concerns revolving around the question of ethics have been emerging from the #class exhibition?

JD: That is such a gigantic question. Here’s a sampling of the ethical concerns that have been raised and discussed at #class:

- Do different ethics apply to the art world than to the rest of the world?

- Is individual artistic ambition compatible with collective artistic activism?

- Is the commercial art system elevating the best art and artists? If not, should we try to change it?

- Should we work to expand access to art beyond the wealthy/well-educated/big-city-residing elite?

- What can be done about commercial galleries who don’t pay their artists?

- What can/should be done about gender inequities in the art industry?

- Should galleries be regulated? Licensed? Would this ensure better business practices?

- How does one define success in art? Is it reasonable that even “successful” artists have day jobs?

- Does anyone benefit from the proliferation of artists getting MFA/BFA degrees aside from the schools?

- Should artists work for free?

A view from inside one of the many events. This one featured the W.A.G.E. group. (Photo courtesy of the author)

HV: The biggest criticism of #class I’ve heard is that there is no resolution to all of these issues you raise and many people don’t see the point. You obviously do, so what’s the point? What will come out of #class?

JD: No, we have not arrived at a simple solution to the problems in the art market. The premise of #class was that it would be an exploration. #class created a platform for addressing problems in the art industry as a community. If a single resolution emerged, it would be unlikely to serve very many people’s interests. We created a place for discussion and exploration. What emerged are some essential, though perhaps unresolvable, paradoxes in the art endeavor and the art market. Some of these my collaborator William Powhida enumerated eloquently in his Art21 blog post (we simultaneously value originality and tradition, progress and stability, invention and preservation).

In addition, artists need complete individual freedom to pursue our work, but must cooperate collectively if we want to improve conditions for art and artists as a whole. Art’s dependence on a small slice of the wealthy class gives us freedom from mass opinion but also enforces a market-driven definition of success.

Paradoxes and confusion notwithstanding, our #class discussions have pointed us toward some modest avenues for positive change:

- Work toward better public arts education to build the next generation of artists, art workers and art lovers, and improve the general public’s attitude toward contemporary art.

- Advocate for artists to get paid fairly for their work, both at the gallery level (this may mean contracts!) and at the museum and non-profit level (asking for exhibition fees when often there are none in the budget).

- Since there are many more artists than available spaces to show, it could become a much more accepted practice for artists to create and run their own exhibitions in whatever spaces they can find. Social media makes it possible to publicize these events better than ever before.

- Build on the 20×200 model for selling work in volume at prices that are affordable to moderate-income people.

From the "Jennifer Dalton is a Scientist - Not!" exhibition at Brooklyn's Smack Mellon Gallery in early 2008. (Photo courtesy of the artist)

Also, having read William’s Art21 blog post, “The Conflation of Ethics and Morality,” I would like to append my answer to your related question. I would add this to what I already said: an individual’s disciplined adherence to her culture’s ethical guidelines can only be driven by personal morality. This morality can be arrived at through other means than belief or faith structures. As I wrote in my first few answers to you, a sense of right and wrong can come through the simple idea that the world won’t suck quite so much if we each stop putting our own short-term interests ahead of everyone else’s long-term ones. I would add that in my opinion, the art world is not such a tolerant place. We don’t like conservatives, even socially-liberal-fiscally-conservative ones. I don’t remember any art world McCain fundraisers in Fall 2008. Our commitment to free expression is limited to the types of “transgressions” we are all entirely comfortable with. Try making artwork about your Christianity and see how many galleries will exhibit it. The art world could benefit by being open to more truly uncomfortable dialogues.

HV: What was the point during #class that made you the most uncomfortable? There must have been a moment where you realized you felt out of your element.

JD: I was uncomfortable on so many occasions! #class pushed us way out of our comfort zones. I am someone who prefers to struggle privately with my work and not be personally on display, and #class made that impossible on a daily basis. Amazingly, throughout the course of the show, I became somewhat desensitized to the types of situations that have tormented me ever since my childhood piano recitals. I hope the effect lasts!

Still, I was probably most uncomfortable during “The Writer Is IN,” an event run by Sarah Schmerler, who generously offered to write artist statements on the spot. I expected to sit safely in the back while she helped other artists who may have come specifically to get her assistance, but she asked me to be her first guinea pig, challenging me to start “writing” an artist statement for myself aloud in front of the group of other artists. She, of course, had no idea of my public speaking phobia, and meanwhile every intelligent thought immediately exited my brain. I stumbled awkwardly along, meeting with her disapproval until William Powhida broke the spell by observing that this was the most authoritarian of any #class event yet. His welcome interruption allowed me a chance to gather my wits off the floor.

Spotted on the chalkboards of #class (Photo courtesy of the author)

HV: And what was the biggest surprise you encountered during #class? Did anything shift your thinking about a topic radically?

JD: My biggest surprise was how well the show was received and how a community built up around it. William and I often did not know what in the hell we were doing and many times were mildly terrified. But over and over again the scheduled-participants and the visitor-participants rose to the occasion and we had great events and fascinating discussions. Sometimes the discussions were launched by specific presentations or performances, but sometimes they occurred out of thin air in response to nothing more than a simple topic presented, like “The System Works” or “The System Doesn’t Work.”

I was very impressed with the willingness of strangers to sit down and talk about contentious subjects together peacefully and intelligently without much facilitation. I now think there is an enormous untapped reserve of positive energy in the art world that we could do something good with. After a rest, perhaps we will have to start figuring out what on earth that should be!