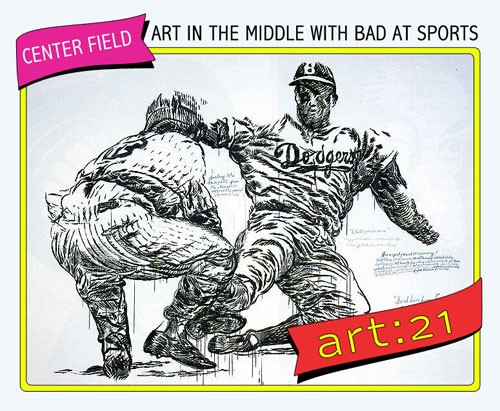

"Raymond Pettibon" 1999-2000. Installation view at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo by Joshua White. Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

Recently, Bad at Sports was invited to exhibit at apexart, an alternative gallery space in New York known for presenting innovative thematic exhibitions and public programs. In order to take advantage of this opportunity, we as a group had to confront a few logistical as well as conceptual hurdles. First and foremost was the question of how to transfer the “Bad at Sports experience,” as it were, to a gallery setting.

Bad at Sports exists as a series of conversations and interviews that sometimes take place as live in-person events but are usually pre-recorded and streamed online or downloaded from our website. We also have a blog that focuses mostly on news, reviews, Chicago art commentary, and other fun and irreverent stuff. So the question for us was, how do we “exhibit” the work of the group, when what that work consists of is, ultimately, a dynamic, intangible and all-too human set of social relationships? Another way of putting it, offered by B@S co-founder Richard Holland: “we are a podcast and work in intangible audio, we don’t maintain offices, we go to the person we are recording, the entire show’s artifactual footprint would fit into a grocery bag and looks like a Radio Shack threw up.”

Because our exhibition would be taking place in New York, live events and interviews could not occur with the frequency that might be possible in Chicago. Thus the gallery would need to be filled with something other than conversation. As a group, we hashed over a number of possibilities. Should we hire a shrink to psychoanalyze exhibition visitors? Should we platform the space and offer it to other groups for short periods of time? Or – this one was Richard’s suggestion– should we duct tape B@S co-founder Duncan MacKenzie to the wall naked and have that be the exhibition?

The questions that Bad at Sports faced about how to convey what we do within a one or two-room gallery space are increasingly common ones. Practices that take social rather than objective material forms are not always ready-made for the white cube and yet they represent some of the most important developments in contemporary artistic practice over the past 15 years.

I wanted to learn a bit more about how other artists and art professionals have approached these issues, starting with Lorelei Stewart and Anthony Elms, two Chicago-area curators who have extensive experience presenting socially-oriented art in a gallery setting. Stewart and Elms are the director and assistant director, respectively, of Gallery 400 at the University of Illinois at Chicago, a highly regarded university art gallery. Gallery 400 is one of many nonprofit art spaces in Chicago that regularly present social practice and “event-based” art (spoke, threewalls and Hyde Park Art Center are just three of countless other examples I could offer).

Stewart told me that when working with MFA students in UIC’s art department, she often finds that those who create works of a social nature have difficulty finding a coherent way to present their work when thesis exhibition time rolls around. “I’ve wondered what the issue is,” she says. “Is it a graphic design issue, one of how to graphically present the work in text and image form? Is it an exhibition display technique issue, in which decisions of what to include or exclude are difficult when the artist has concentrated so much of his/her time on the enactment rather than this final presentation point? Or is it that the answer is inherent to the project and the facility of the artist in making the transition from enactment to presentation?”

However, both Stewart and Elms disagreed with my assumption that socially-oriented art poses inherently different challenges to the gallery than do other forms of art. “I don’t see the difference in working with a social practice exhibition versus an event-based exhibition versus painting versus whatever,” Elms told me. “Obviously the space will look different. But with every exhibition, the problem is one of setting the gallery experience in a way to fulfill the needs of the project. I don’t see shows of art objects as ‘un-dynamic,’ and therefore do not see exhibition spaces as static. The question becomes how to do justice to the material at hand.”

While the ethos behind Gallery 400’s program is not quite “anything goes,” its exhibition history reads as a living primer on experimental exhibition practices that are deeply sympathetic to the needs of artists. Recently, Gallery 400 hosted a project by the Chicago group Temporary Services (Brett Bloom, Salem Collo-Julin, and Marc Fischer) who employ a range of critical strategies and formats in their work. Their exhibition at Gallery 400 focused on one of their latest projects: Art Work: A National Conversation on Art, Labor, and Economics, a newspaper and accompanying website containing writings and images from artists, activists, writers, critics, and others on the topic of working within depressed economies and how that impacts artistic process, compensation and artistic property.

The exhibition’s main visual device was the display of all forty pages of the newspaper on the gallery’s walls. The space was also used for events and discussions relating to the project. In this case, the gallery space provided the group with an infrastructure as much as it did a mode of information dissemination and display. “On one hand,” Temporary Services told me, “the newspaper really doesn’t need walls and lights and gallery sitters to function as a reading experience. However, the pile of papers that we included in the exhibition (for visitors to take as many as they wanted for free) and the discussions and events that were organized during the exhibition were ultimately more important than hanging the newspaper on the wall.”

Installation view, "Art Work: A National Conversation on Art, Labor and Economics" at Gallery 400, University of Chicago at Illinois

The exhibition gave Temporary Services a place to contextualize the newspaper alongside a selection of their past publications. The gallery itself was a space to conduct events and discussions while also providing promotional and — critical in this case — financial support.

“It was important to us to extend the discussion to Chicago, since we are from here,” the group explained. “Working with Gallery 400 (and a generous donation by Ed Marszewski of Proximity Magazine) allowed us to print 3,000 more newspapers. Gallery 400’s budget also allowed us to split $1,700.00 fairly between all of the contributors to the project, which is not something we could have done without the exhibition.”

After speaking with Stewart, Elms, and Temporary Services, I wanted to see how these issues are approached within a larger museum context. I asked Stephanie Smith, Director of Collections and Exhibitions and Curator of Contemporary Art at the University of Chicago’s Smart Museum of Art about her experiences curating art of a social nature for a museum that has a broad encyclopedic focus. Smith organized the 2002 Smart Museum exhibition Critical Mass, which looked at Chicago-based artists who use activist intentions, conceptual strategies, and experimental artistic approaches to complex social issues (Temporary Services also participated in this show). Last year, Smith co-organized (with the Van Abbemuseum’s director Charles Esche and Research Curator Kerstin Niemann) the exhibition Heartland, which explored art from the Midwest with a particular (though not exclusive) focus on the region’s many artists’ collectives and socially-oriented artistic practices.

In our conversation, Smith emphasized how important it is for museums like the Smart to address this type of work. The past ten years of working within the institution, she says, have involved “our thinking about how to bring social practices into the museum space, and (how to ensure) that the process of bringing this work into the ‘white cube’ doesn’t flatten it out or even kill it.”

Of the artists participating in Heartland, Smith notes that “some brought in clear finished ideas about what they want to do, so there wasn’t a lot of back and forth discussion. With the Detroit Tree of Heaven Woodshop [a group consisting of Mitch Cope, Ingo Vetter, and Annette Weisser that investigates the ways in which a plant normally considered a weed can be used as a sustainable crop], we went back and forth about different things we might try. The group decided to use the modest materials fee that we’d set aside for them to purchase a vacant lot in Detroit and make a Tree of Heaven plantation there.” The exhibition space also included photographs and objects made from Detroit Tree of Heaven wood.

Installation view of projects by Detroit Tree of Heaven Woodshop shown in the exhibition "Heartland" at The Smart Museum of Art

The Smart Museum presents a range of exhibitions in different media and from various historical periods. “It’s fascinating, when you have someone coming to see the Museum’s Rothko, or to see the Chinese funerary sculpture, or 19th-century prints, to have them also be able to encounter works that delve into an activist project about mapping Midwestern energy infrastructure” [as Compass Group did in Heartland], Smith says. “It’s a great way of making a case for the importance of these types of practices within the larger span of art history.”

Smith told me that the project by Detroit Tree of Heaven Woodshop has lived on to yield “something quite wonderful, which is that our collections committee just approved the purchase of a new work” that builds on the project they produced for Heartland. “We’re not just acquiring a static work,” she notes. The project will document the growth of the plantation annually, and will have a forty-year lifespan – the amount of time it will take for the plantation trees to reach fruition.

View of the Detroit Tree of Heaven Farm; purchased by Detroit Tree of Heaven Woodshop for the exhibition "Heartland" at the Smart Museum of Art.

Socially-oriented practices clearly inspire new ways of thinking on the part of curators and audiences, but on the other hand, artists who work in these areas may find that the gallery can challenge them, too, in ways that are productive and invigorating. Richard Holland says that the opportunity to exhibit in a gallery setting encouraged Bad at Sports “to come up with new ways to expand our ideas of how we satisfied the goals of our project.” After much internal discussion taking place across kitchen tables and computer monitors, the group honed in on the notion of the archive. One of the most significant aspects of Bad at Sports’ project is the publicly-accessible archive of hundreds of conversations about art in Chicago and elsewhere that have been recorded over the past five years. The group decided to solicit a visual counterpart to this audio archive in the form of artifact-objects sent in by the 300 guests that have been on the show. Holland describes the resulting exhibition, titled Don’t Piss On Me and Tell Me It’s Raining, as “truly a cabinet of wonder. Our method emphasized the positive, it (was) non-hierarchical, and it let people be silly if they felt so inclined.” The Bad at Sports experience in a nutshell.

Installation view, "Don't Piss on Me and Tell Me It's Raining," organized by Bad at Sports for apexart, New York.