I am not a professor of ethics. I have been a curator and a director of new media at a major art museum, but I am first and foremost an art historian. You will therefore permit me to repeat, emphatically, that I am not a professor of ethics. So reader, if you are one, or if you have a B.A., M.A., or a Ph.D. in philosophy, you may be profoundly disappointed and/or annoyed by this post.

Here is how it all began. In 2004/05, after some fifteen years in the wonderful world of art museums, I began to think about how the ubiquity of technologies in service at museums might be impacting professional behaviors—not new technologies like cloud-computing, or mobile technologies, or even augmented realities and gaming, but habits associated with the use of familiar technologies like telephones, the color copier, and the Internet.

Ultimately I was offered the opportunity to produce a brief article on the subject entitled “New Technologies, Old Dilemmas: Ethics and the Museum Professional,” in the American Association of Museum’s 2007 publication The Digital Museum: A Think Guide. And recently, for my sins, I’ve been able to enlarge the scope of the project and teach in ethics for museum professionals as part of the Johns Hopkins M.A. in Museum Studies.

In the class we cover a wide range of topics, which might better be described as good business practices rather than ethics. Below is a representative example of weekly topics:

- Museums, Mission Statements, and Ethics Statements & Policies

- Ethics and Information Systems

- Ethics and Copyright

- Ethics and Engaging Audiences: Gaming and Social Media

- Ethics and Collection Care and Research

- Ethics and Fiduciary Responsibility

The first thing we discuss is “Big Ethics,” which are the issues that students and museum professionals (except for those involved) typically want to discuss. These are the kinds of ethical issues that make headlines and are emotional touchstones for museums, such as stolen artifacts, repatriation, executive abuse of resources or privilege, treasure-hunting, etc. These students are smart and opinionated and they want to talk about big issues—not the use of color copiers by museum employees.

And so I ask my students to consider the following questions: Once we’ve determined that something is a big issue, how do we evaluate the problem? Is it an issue of broad concern across all museums—collecting and non-collecting institutions, big and small? How and when does an issue impact our constituents? And what constituents and how many are impacted by an issue? Does size really matter? Are the issues that get the most press necessarily those that are the most damaging to museums?

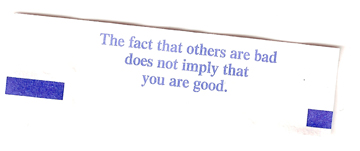

At a Chinese restaurant, I once received the following fortune in my cookie: “The fact that others are bad does not imply that you are good.” One of my primary goals for the class is that students, who begin with the opinion that ethics is something that applies to other people and that ethics statements really have nothing to do with them and their careers, discover a compass within themselves.

For that very reason, an important week early in the class is devoted to the review and analysis of the AAM Code of Ethics and ICOM Code of Ethics. While this may not be their favorite activity—and it is some heavy reading—the students learn a great deal about their intended profession by a survey of these two documents. Museum studies students are like students anywhere — some will embrace assignments wholeheartedly, while others feel that analyzing codes of ethics is busy work.

It doesn’t take the students long to figure out the major difference between the two codes. Here are a couple of defining statements from students:

- The AAM document is written with a narrative style and frames ethical insights much like a parent who wants us to know about the best ethical behavior.

- ICOM, on the other hand, is set out like a law code, even though it expects that museums will go beyond the “minimum standards.”

The key to this exercise is for students to have the opportunity to discuss the pros and cons of the two different approaches. Once they are engaged in dialogue, the codes become a launching pad and the students go off on their own and find associated articles. They frequently cite Mark Gold’s article “Nothing Ethical About It,” any one of a number of “Law & Ethics” articles by Elizabeth Merritt and Erik Ledbetter, or offer scenarios for consideration that don’t seem to be covered by current codes. They agree with some parts of the codes and find other parts either gratuitous or just not good enough. At this point, two things have happened. Students have understood and internalized, to an extent, current codes of ethics and they can visualize problems, opportunities, and imagine a better code.

Oh, and one other thing that sets these students apart is that they’ve actually read both codes of ethics for their professional organizations. Can you make the same claim?