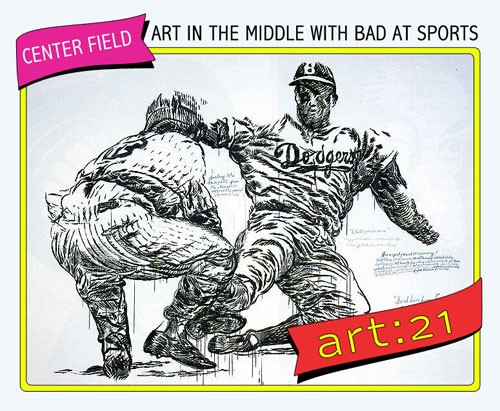

"Raymond Pettibon" 1999-2000. Installation view at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo by Joshua White. Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

While sitting in his office listening to some soon to be released albums, Ken Shipley quickly noted, “we have found a way as a record label to be like a band.” Founded in 2003 by Shipley, Tom Lunt, and Rob Sevier, Numero Group has done just that. With almost 60 releases to date, the company has garnered a devoted fan base and established itself as a leading archival record label. Similar to the alternative apartment spaces within Chicago, Numero Group has set up shop on the first floor of a three-story brick home here in town. With series like Eccentric Soul, Good God!, and Cult Cargo, it has traveled far and wide in search of records that share not only a distinct sound but also a unique story.

Meg Onli: You have spoken before about building your compilations based on not only your (and everyone else in Numero Group’s) collection, but also that of retired DJs, performers, and fans. Could you talk about how you would typically go about making a compilation?

Ken Shipley: I think there is a misnomer about what it is that we actually do. The amount of time that we spend in the crates is really minimal. Most of the projects that we are working on we found through other research or development or work that we have already done. Like in the case of this Lowlands record that we just made, digging for the records are almost impossible. Two records came out of the entire studio, but we ended up buying the entire contents of the studio. I think people get the impression that we are crazy crate diggers that are running around the world looking for records.

MO: Record digging has become a romanticized act. Do you think that is why the term “music archeology” is often linked to your work, even though it may be inaccurate?

KS: I think what we do is more like cultural anthropology than music anthropology. I think people get into this archeology thing because it is a really good way to put the digging aspect into it. Like I said, our fingernails do not get dirty on a lot of projects. There are some, certainly, but for the most part it’s really just cultural anthropology. There are very few ‘arc of the covenants’ that are waiting to be found, and we have found a handful of them, don’t get me wrong, but a lot of what you are finding are small things.

***

When I first discovered Numero Group with its album, Eccentric Soul: The Big Mack Label, I was impressed by the research that was put into the liner notes. Unlike traditional liner notes that often housed lyrics and song credits, these gave a full history of the label with a thoughtful essay, and visual documentation that included photographs, business cards, and handwritten notes. I had a chance to check out some liner notes Numero Group were working on and talk to Ken about how they decided to accompany their records with a history of each project.

***

KS: When we make a record, we want to make something that is not only aurally orally satisfying but also satisfying as a story to read. You have a two-prong element, you have a good listen, but it is also a really fascinating story…I will be the first person to admit that we certainly have records [where] the story is stronger than the music. A lot of the time, we make those because it is a great story and the records are kind of like the soundtrack. Not every great soundtrack to a great movie is a great soundtrack. There are plenty of fantastic movies that have [bad] soundtracks. I don’t think we have ever made a shitty soundtrack, but we have made some things that are very curious.

There are a lot of reissue companies out there that, I won’t name any names, write a set of liner notes and they’re filled with things like, ‘There are two known copies of this record.’ They want to insert themselves as a character into the story. Numero is not a character in the story of a fifty-year-old black record label. It’s just not.

MO: Some people have noted your sixth album, Cult Cargo: Belize City Boil Up as a turning point in your production. This past year, you have released a book, Light on the South Side (documenting the club life of Chicago’s South Side from 1975-1977) and a film, Celestial Navigations (archiving the work of Al Jarnow). What milestones do you see in your catalog?

KS: There is a trajectory over the first twelve records, and it just gets better. You can see a progression. I can see how we got to thirteen, fourteen, fifteen. We hit our stride in those records. In one of them, we went to the Bahamas, did our second Miami record, and Don’t Stop: Recording Tap in one trip. The record that is really the turning point is Twinight. It was the record that we put so much into because we knew we could not go back from this.

I think the book is certainly one point for us. When the dummy came back from the printer, we asked ourselves, ‘How do [we] go back to [picks up a cd booklet] this after [we] made that?’ It does not compute. Everything we have been doing since then has to be as great as that.

***

This month, Numero will be releasing a curiosity within its collection, Eccentric Breaks and Beats, an album that is essentially a bootleg of its catalog. With no “real” beginning or end, the 40-minute album mixes samples from many of their records. Weaving Baltimore girl groups with soul music from the Bahamas, the pastiche seamlessly blends the songs I already liked into what I imagine would be perfect lounge music (the kind you would want to hear in a mod blaxploitation film). As we listened to some of Ken’s favorite samples from the record, I checked out the album artwork. Unlike anything in their collection, the cover is in the style of a 90s rap compilation, fully equipped with a skeleton and a bad graffiti font. When asked about the artwork for the album, Ken discussed how they decided to use a style not typical of their previous works.

***

KS: When we decided to make this record, we wondered how we could make a record that feels like a fake. Something that is like a really good forgery, when in fact it is a forgery. The music itself is an edit. It is a very long edit of a bunch of Numero stuff. We looked at the Ultimate Breaks and Beats cover and [thought] that stupid skull and ghetto [font] really kind of worked for us. It was like we were paying tribute to a shitty time in making records as in how low the expectations were. [In this album] we are not trying to tell the story of the bootleg. So we said, ‘Why don’t we make this?’ [He hands me a small booklet that reads, ‘1 stop records, 2348 S. Marshall Field’]

The back of the record says, “distributed by Little Village One Stop Record Exchange,” which is our fake distribution company. So we asked ourselves, ‘what other records would One Stop Record Exchange do?’ That is how we came up with it. These are the liner notes for a record that basically doesn’t exist.

MO: Any major record company would have shut the album down. How did you guys decide to publish it?

KS: We heard the record and we really liked it and we asked, ‘how do we monetize this instead of taking the Danger Mouse Grey Album approach of just shutting it down?’ We could have just pulled it out of print, but that is where it becomes something that is really scarce. The Danger Mouse record bootlegged far more after the bootleg was shut down. It kind of created more mystique for that record, which is great, but also nobody got paid. We wanted everyone to win on this record, every artist sampled. It doesn’t just have to be the distributors, the record stores, and some guy selling them for $4.50 a piece. We thought it was a really cool record and we thought ‘God, we can make this. Lets not stifle it, let’s let it bloom.’

I feel like this record is going to transcend our audience and become a record for a lot of different people. It’s just such a cool listen that I think people are going to gravitate towards it. Does it get picked up? Do people want to sample it? That is why I think it can be a bigger record, let’s say, than an Eccentric Soul album or the Fern Jones. And because it is in two twenty-minute segments, there is no breaking it up. There is no single. You just listen to it. I really liken it to the Avalanche’s record. I do not have a favorite track. I like it all the way through.

MO: Well, the album is breaking the convention of what a track should be. You are not limited to your 2 to 4 minutes in order for it to be a single that might be played on the radio or made into a music video.

KS: We don’t care about the single. We don’t have any singles. We can live within the margins of the music business and be extremely successful. We have a completely different mindset. If you are in this office right now, there are no brushed metal nameplates, there are no glass doors. There is nothing like that. That is an old world, which is a dying world. The new music business is going to be built in people’s basements, in run-down little houses, and all kinds of secondary environments that don’t have to be on the fourteenth floor of a building in Manhattan.