The passing of Louise Bourgeois (Season 1) naturally prompted a host of critics to reflect on her life and artwork. They have written of her famed sculptures and textiles, recurring spider motif, pioneering exhibitions, childhood traumas, and the Sunday salons in her Chelsea home. Now, what about Bourgeois’s cooking?

They say that cooking is, like other art forms, an expression of one’s inner self. As I read Bourgeois’s obituaries, many of them recalling the artist’s charms and spunk, I began to wonder if she cooked? If her approach to food was anything like her approach to art? If her cooking looked like her artwork? Or what her artwork might tell us about her cooking? While these inquiries might seem random, chef Mario Batali has pointed out that “food, even more than art, allows an admirer to relate to [an] artist on common ground,” and there is perhaps no “better way to come to appreciate and understand an artist than through [her] appetite.” Luckily, I found that Bourgeois contributed to at least three cookbooks in her lifetime: The Museum of Modern Art’s Artists’ Cookbook (1977) by Madeleine Conway and Nancy Kirk, Food Sex Art: The Starving Artists’ Cookbook (1991) by Paul Lamarre and Melissa P. Wolf (aka EIDIA), and The Artist’s Palate: Cooking with the World’s Greatest Artists (2003) by Frank Fedele.

Louise Bourgeois, "The Destruction of the Father," 1974. Plaster, latex, wood, fabric and red light, 93 5/8 x 142 5/8 x 97 7/8 in. Courtesy Cheim & Read, Hauser & Wirth, and Galerie Karsten Greve. Photo: Rafael Lobato.

In The Museum of Modern Art’s Artists’ Cookbook, a black and white photograph shows Bourgeois, then in her mid-sixties, sitting on top of an old brick and mortar stove with a collection of pots and pans placed near her feet. There are no pictures of Bourgeois’s cooking or artwork, only her portrait and words. These pages give more of a sense of her character than the essence of her cooking:

I was told as a child in France that cooking is the way to a man’s heart. Today I know that the notion is absurd, but I believed it for a very long time. My mother was in delicate health and could not cope with long hours of work in the kitchen. To please her, I took on the responsibility of seeing to it that my father had dinner. It wasn’t easy. He often came home very late. I waited for hours to make sure that the food stayed hot and fresh—and I became expert at just that. When my father appeared and wanted a steak, I cooked it for him. In those days, a man had the right to have his food ready for him at all times. During my student years I did not cook at all. The memory of those many wasted hours lingered. I subsisted on yogurt, honey, and pumpernickel bread. I still eat the same foods today.

By now, it is well known that Bourgeois’s early family life, with an ill mother and adulterous father, shaped her sculptures, drawings, and prints. From the above quote, it is apparent that her childhood also had a direct effect on her relationship to food and the kitchen. This plays out in her tableau The Destruction of the Father (1974), which was, according to her New York Times obituary, inspired by “a fantasy from childhood in which a pompous father, whose presence deadens the dinner hour night after night, is pulled onto the table by other family members, dismembered and gobbled up.”

Louise Bourgeois and her father Louis, 1948. Courtesy Louise Bourgeois Studio and DB Art Mag. © Copyright Louise Bourgeois, 2004. All rights reserved.

Today, it’s hard to imagine that Bourgeois, the “Grande Dame of American sculptors” and an artist who endured and achieved so much, could ever have been unsure of herself. Artists’ Cookbook reveals that Bourgeois had a vulnerable side, particularly when it came to cooking. Bourgeois is quoted as saying, “I love to cook. It amuses and relaxes me, but when it comes time to serve the food, I lose confidence in myself.” She goes on to recount preparing boeuf à la mode for her family, only to toss it out of the window before anyone could taste it; waiting for them to come to the table and approve of her cooking was “agony.”

Following these anecdotes are eleven recipes from Bourgeois. They include: Laitance Bourgeois, a traditional French dish made of fish eggs, butter, and lemon juice; Veal Blanquette Lippe with boiled potatoes; Pressure-Cooked Endive and Fennel, served “French style” on a platter covered with a white towel; and a sundae made of coffee ice cream, marzipan, and milk and decorated with candied violets.

“You have to be very sculpture conscious when you’re cooking,” said Bourgeois in Food Sex Art: The Starving Artists’ Cookbook. An image of her hanging phallic sculpture Janus (1968) practically overshadows her recipe for “Oxtail.” There is something to be said here for the unacknowledged relationship between recipe and sculpture. Oxtail, prior to being butchered, very much resembles an uncircumcised penis. Sometimes animal penis and tail are both classified as waste; othertimes, in some cultures, they are considered delicacies or (like art) luxury items.

Louise Bourgeois, "Janus," 1968. Bronze, dark and polished patina, hanging piece. Courtesy Cheim & Read, Galerie Karsten Greve and Galerie Hauser & Wirth © Louise Bourgeois. Photo: Christopher Burke.

Bourgeois’s recipe calls for seven “young stud” oxtails, four “very young and fresh” veal feet, leeks, a half bottle of wine, some olive oil, thyme, laurel (bay) leaves, and a few other ingredients. This mixture of meat (boiled in a pressure cooker until the flesh “falls off the bone”), fermented fruit juice, and fragrant herbs seems to encapsulate the artist’s life work: a well seasoned balance of bulky and delicate, the raw and the cooked. Janus, Bourgeois said, is “a reference to the kind of polarity we represent.”

It seems that oxtails were among Bourgeois’s favorite foods. In The Artist’s Palate, published nearly 16 years after The Starving Artists’ Cookbook, her recipe for Oxtail Stew appears alongside an image of her bronze floor sculpture, Avenza Revisited II (1968-69). This piece bears striking similarity to a chopped oxtail.

Louise Bourgeois, "Avenza Revisited II," 1968-1969. Bronze, silver nitrate patina, 51 1/2 x 41 x 75 1/2"; 130.8 x 104.1 x 191.7 cm. Courtesy Cheim & Read and Hauser & Wirth.

The recipe, slightly different from her earlier oxtail dish, is accompanied by a story in which the actual meat overlaps with her studio practice.

I went to the wholesale meat market on 14th street in New York, and bought two packets of [whole] oxtails…I got them home and realized I had to cut them into about five pieces per tail. Being a sculptor, I put them on my band saw. The bones were so hard the band saw[‘s] blades snapped. I went to the corner butcher to ask him to do it with his rotary disk saw; he said ‘I would do this for a customer, too bad you went behind my back.’ I learned my lesson and since then I rely on my local butcher.

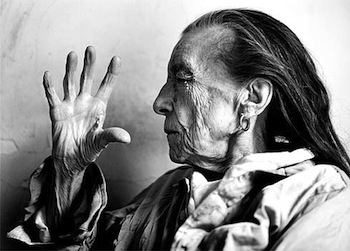

On the page opposite her sculpture is a portrait of the artist captured in more recent years, her hair thin and her skin peppered with age spots. Bourgeois holds a small frying pan with a soupy film covering the base and a shallow pile of noodles pushed to one side. It appears that she is either sniffing or just about to taste this “well-cooked” linguini with American cheese, a meal that her assistant made for her every Sunday. The dish was always followed by coffee ice cream — if you remember, a dessert that she named twenty-five years earlier in Artists’ Cookbook. It is worth mentioning that critic Lance Esplund compared two spiral forms that hung above Bourgeois’ sculpture Spider Couple (2003), when displayed at the Guggenheim, to soft-serve ice cream. He also noted that the comforts of home (of which food is always one) was a theme of this last retrospective exhibition.

If one thing is evident from these three cookbooks, it’s that food, cooking, and art were for Bourgeois truly inseparable.

The Artist’s Palate: Cooking with the World’s Greatest Artists can be purchased via Amazon.com. The Museum of Modern Art’s Artists’ Cookbook and Food Sex Art: The Starving Artists’ Cookbook are both held in the library collection of the Museum of Modern Art. Many thanks to MoMA librarian Jennifer Tobias for her assistance.