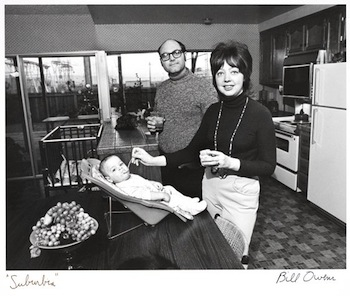

Bill Owens, "We're really happy. Our kids are healthy, we eat good food and we have a...", 1971 (printed 1977). Gelatin silver print, 6 5/16 in. x 8 1/16 in. Collection SFMOMA, Gift of John Berggruen. © Bill Owens.

In the early 1970s, Bill Owens began to document the suburban boom in the California Bay Area. Every Saturday for a year, he photographed middle-class Americans in and around their homes, posed in modern kitchens, barbequing in the backyard, seated around the dinner table, and hosting Tupperware parties. Food figures prominently into the artist’s portraits of suburban life. In Untitled (Joy of Cooking) (1971), currently on view in the Getty Center exhibition In Focus: Tasteful Pictures, Owens has captured a kitchen pantry stocked with canned and packaged foodstuffs. Such an abundance of imitation foods was, at that time, a sign of prosperity. The tables have certainly turned. That same pantry today would suggest poverty, obesity, and poor health.

The hidden costs of living the American Dream — embodied in part by the “convenience” foods pictured in Untitled (Joy of Cooking) — has led to a rethinking of the suburbs and the current push to return to food ways of earlier generations. Enter the work of Los Angeles-based artist Fritz Haeg.

Fritz Haeg, "Edible Estates Regional Prototype Garden #6 (installation view)," 2008. Commissioned by Contemporary Museum Baltimore. Courtesy the artist and The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum. Photo: Leslie Furlong.

Fritz Haeg, "Edible Estates Regional Prototype Garden #6 (installation view)," 2008. Commissioned by Contemporary Museum Baltimore. Courtesy the artist and The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum. Photo: Leslie Furlong.

Haeg’s ongoing project, Edible Estates, transforms front lawns — an icon of suburban America — into spaces for natural food production, or “edible landscapes.” In the second edition of his book, Edible Estates: Attack on the Front Lawn, released earlier this year, Haeg sites Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello with its lush green forefront as the “de facto” model for the American home. He asks us to consider how American neighborhoods might look today if Jefferson had planted his legendary crops in front of his house instead of hiding them from plain view? “Edible Estates,” Haeg said to me in a recent interview, “are all about resistance in a way — resisting contemporary situations and preconceptions of contemporary home.”

Five years ago this month, Haeg planted his first regional prototype in Salina, Kansas, at the residence of Stan and Priti Cox. Their small field of okra, green chiles, Swiss chard, eggplant, curry leaf tree, tomatoes, and other herbs and vegetables was planted on Independence Day. The date and location (Salina is almost exactly the physical center of the United States) were symbolic of the project’s impetus. Edible Estates was inspired by the 2004 election and Bush administration. Haeg explains:

The project was a response to the political situation in [the United States] and a real desire to do a project that got out of an insular art world dialogue. [I was] really wanting to do a project for and about the entire country—what we all believed in, what our values were, where we were headed. At the time you could argue that a more expansive dialogue with the general public was more urgent than ever.

The Edible Estates project responds to uniformity and division, represented by both the sprawling green lawn and the election, with biodiversity and community engagement. Local agriculture not only impacts how a place looks, but also how its people interact. Each Edible Estate is unique to its location, using plants native to the area and growing climate. Though the gardens are usually commissioned by a museum or not-for-profit space, the design is done in accordance with the inhabitant’s wishes. Haeg works directly with homeowners and volunteers to bring these foodscapes to fruition. He has created nine Edible Estates to date. The most recent was planted on the grounds of The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, Connecticut.

Fritz Haeg, General garden view, "Edible Estate #9," 2010. Installation view at The Aldrich. Courtesy The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum.

Fritz Haeg, "Dancing Boardwalk," 2010. Installation view at The Aldrich. Courtesy The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum.

The Aldrich exhibition, Something for Everyone, is a survey of different projects that Haeg has been working on for the past five years. The exhibition includes an Edible Estate (tended by museum staff), a dancing boardwalk, a schoolhouse, compost piles, and a family room “inversion” (a local resident/family will move their living room furniture into The Aldrich’s atrium, and then organize a series of salon gatherings at their home). “This is kind of a new development,” said Haeg. “All of the work that I had been doing previously is laser focused on particular situations, very particular responsive thoughts to how we’re living. The Aldrich project is a whole bunch of those applied simultaneously to a piece of property that used to be a private residence…the [individual projects] start to talk to each other and have a conversation.”

Fritz Haeg, "Edible Estates Regional Prototype Garden #4" (installation view), 2007. Commissioned by Tate Modern, London. Courtesy the artist and The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum. Photo: Jane Sabire.

To be sure, Edible Estates is not just about food, the suburbs or even gardening. When asked how the project has surprised him along the way, Haeg responded:

By the time I planted the second garden in Los Angeles, it became apparent just how loaded the project was in terms of questioning the icon of the front lawn [which] means inherently questioning the values of America. And, also, how it was at this kind of nexus of the environment, water, food, neighborhood, community, art, and aesthetics…diversity, taste, and pleasure. It was only after I had done the project for a couple years that I realized what a broad, expansive series of issues these little gardens were at the receiving end of.

The dialogue around food has of course grown alongside Haeg’s project (case in point: this column). Some of the circumstances that led to Edible Estates have also changed, most notably at the White House, where there is not only a new First Family but a vegetable garden too. (In March 2009, Haeg wrote an editorial for The Guardian about why the Obamas’ vegetable patch matters.) “It’s encouraging and exciting,” said Haeg of the White House garden,”but it’s also evidence that there’s less need, in a way, for me to be doing this specific art project. There are plenty of people who are doing it.” He recognizes, however, that some conditions will not be quick to disappear:

I drive around L.A. and see people in line to get take-out from a fast food place and I can’t believe it. I can’t believe people still eat like that…I mean, there are certain places where people just don’t have access to the food that they should in a civilized culture. So, that’s part of the reason that people are still in line at those places, because that’s all they have. But it also is evidence that we’ve just begun the conversation; we haven’t really solved many of the problems yet.

Edible Estates will continue, Haeg says, as long as there are invitations that “make sense” for the circumstances they present.

The parallels and differences between Owens’s Suburbia series and Haeg’s Edible Estates are many. Some forty years after Owens captured the cultural shift to the suburbs of Northern California, Haeg, working in Southern Californian and beyond, is fostering what will perhaps be the next change in these communities. I suspect that in another forty years from now, food and front lawns will continue to show us where we’ve come from and where we might be going.

Something For Everyone is on view at The Aldrich through January 2, 2011. Visit Haeg’s website to read more about Edible Estates.