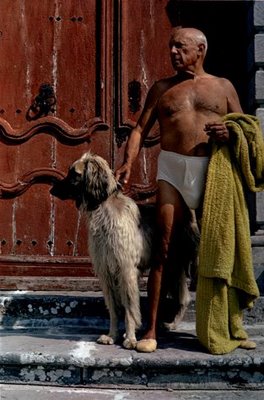

Pablo Picasso walking the dog

The “must-see show of the summer” is not, despite what the adverts on the buses might have you believe, the John Richardson-curated Picasso show at Gagosian Gallery. Not nearly as bedazzling as his last Picasso show, the 2009 Mosqueteros show at Gagosian New York, the show’s museum-like hush-hush installation is a smokescreen for quite a lot of churned-out joie-de-vivre stuff made after a boozy lunch with Cary Grant and the crown prince of Monaco. There’s more than enough great, charming work, especially the sculptures, to go around – after all, this isn’t the blue period – but after a while you get tired of being beaten about the head about how great the south of France is. The Picasso show is one of a few predictable offerings in London venues this summer – Surrealism at the Barbican, limp self-indulgence at the Hayward (Ernesto Neto), another dry-as-dust photography show at Tate Modern (Exposed), none of which should overshadow the fact that two of the most fascinating, prolific, and historically significant American artists are making their debuts in the city this summer. And they’re both dead.

That Alice Neel is one of the very great post-war portrait painters, far outstripping one-trick pony contenders like Lucian Freud, Alex Katz, Frank Auerbach, or anyone else you care to mention – compare, say, Neel’s magisterial portrait of Andy Warhol and any of Freud’s tired crusty aristocrats, each a different shade and texture of stale bread – should be cause for general celebration, but it’s only this year, twenty-six years after her death, that the first solo show of Neel is being held in London. To give some sense of how belated the show at the Whitechapel is, consider the facts. Neel was born in 1900 and came to prominence in the US in the 1970s, which means she came of age artistically in a thicket of -isms. This makes her, for art historians (watch out!) “problematic,” since her work is of no fixed aesthetic abode. Having a narrative to explain the work is the next best thing.

Female artists (like “outsider artists”) are required to have an overarching narrative (cf. Sylvia Plath, Eva Hesse, Virginia Woolf, Frida Kahlo, and so on) in order to make sense of their work – as though their creativity needed a sort of justification within a narrative of female experience. Neel’s narrative is of the batty old dame who made old-fashioned art in the face of seismic change. Her resistance is, like Freud’s, posited as enough to hang a reputation on. And yet it doesn’t take a master’s in art history to spot the difference between the portraits made by those doggedly resisting artistic change – see the appalling photo-realism dominating the ever-depressing BP Portrait Award in London – and Neel’s spare, poised works, which are every bit as conceptually and aesthetically compelling as anything produced at the time.

Alice Neel, "Self Portrait," 1980

Take Neel’s self-portrait from 1980. Your initial response on seeing this image of a saggy-bodied elderly lady with the half-moon granny specs sitting in a stripy armchair might be to refer to the sort of frankness we might associate with the late Rembrandt self-portraits. You might even draw parallels – in the bare-facts fleshiness of Neel’s body – with Freud’s voyages into the realm of obesity. But neither of these ideas is really borne out in the work itself. One of Neel’s many strengths as a painter is her ability to turn your expectations sideways, mucking about with the mind’s desire to make the painting seem real. Her paintings barely exist in the mind, in the sense that they’re unmemorable. I mean this as a compliment: their oddities and discontinuities disallow the possibility of posthumous recall. They need to be seen and remake themselves as they do. Look at how her right arm bends into the shoulder fluidly, bonelessly; this is a body felt, not perceived. Look at the legs that seem not to touch the ground, like a small child’s on a swing; this is old age bamboozled by itself. And look, again and again, at that loose, thrown-off line and high-key color set against a background that’s barely there. This is Alice Neel becoming an Alice Neel.

Just as incredibly, Alison Jacques gallery in central London is showing the first London exhibition of Hannah Wilke, who died in 1993. Wilke is a legendary figure of 70s feminist art whose small sculptures in latex, ceramic, and chewing gum are displayed in various ways — as pseudo-minimalist grids, as wall reliefs, and (most famously) worn on the body and photographed. Each sculpture is a delicate fold of clearly genital form. Arranged in Sol LeWitt-ish fields, the pale glazed ceramic works of Elective Affinities (the show’s centrepiece) recall tulips, purses, seashells, and half-formed cups. They link Wilke, perhaps unexpectedly, to the comic double-entendre sculpture of Eva Hesse. Deliberately vulnerable, they radiate a kind of strange coiled power; to touch is to break, to look is to touch. (No wonder she poses with an array of weaponry in one of her self-portrait photos: there’s a threat of violence thrumming underneath even her subtlest works.) In Wilke’s self-portrait photographs, the artist, studded with chewing gum sculptures like points on a map, makes her own body a site of looking (and she looks out, too, in a kind of louche take on fashion photography).

Hannah Wilke, "S.O.S Starification Object Series," 1974. (c) Scharlatt Family

Wilke’s theme is the possession of looking. But what’s most powerfully articulated in the show is her status as sculptor. She should certainly be put alongside the early Lynda Benglis and Richard Tuttle (as well as Hesse) as alchemist of the overlooked, someone capable of whipping up visual authority out of almost nothing. How about a Wilke/Picasso ceramics show, the priapic polymath versus the sly subversive? We’d call it “Pablo Hannah.” Someone call Larry.