What is so compelling about riddles, mysteries, and puzzles? Most people are fascinated by images and objects that are paradoxical or impossible in real life but look oddly convincing and perplexing in 2D. Art:21 Season Four featured contemporary artists Allora & Calzadilla, Mark Bradford, Robert Ryman, and Catherine Sullivan who investigate the boundaries between “abstraction and representation, fact and fiction, order and chaos.” Throughout history, artists have been compelled to explore paradox as contradiction, ambiguity, and truth.

The paradoxical structure of my work is often to engage that place of in-betweenness; to engage it, not to make a picture of it, not to make it its subject, but actually to try to work at that place in a way that demonstrates it, that’s demonstrative, that occupies it. You know it’s very abstract, but concrete.

It would seem that paradox inspires artists to expand their imaginations, derive abstract concepts, and dream bigger.

Art is paradoxical by nature. It both reflects the past and creates the future. It both orders and dis-integrates, and somehow, through the course of both, defies entropy.

Maybe that’s what humans do, too: reflect and create.

Maybe that’s why we need art so badly.

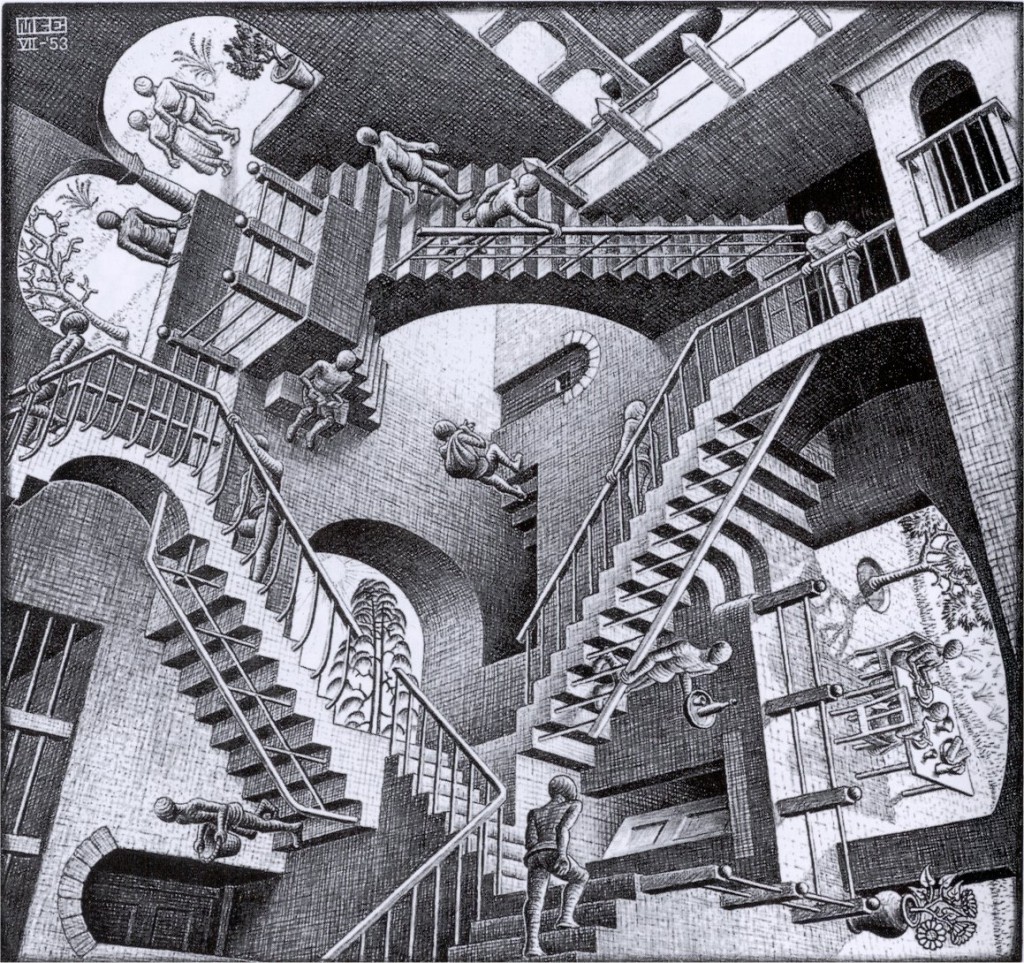

The Penrose stairs is a 2D depiction of a staircase in which the stairs make four 90-degree turns as they ascend or descend yet form a continuous loop, so that a person could climb them forever and never get any higher. This is clearly impossible in 3D but the 2D version achieves this paradox by distorting perspective. The best known examples of Penrose stairs appears in a couple of famous lithographs by M.C. Escher (see top image) and this brings us to Christopher Nolan’s Inception, a film that is billed as a story about dreams but also delves deeper into our fascination with paradox.

Note that this entry is not a review of the film, nor are there any major plot spoilers for those who have yet to see the film. I have seen this film three times on the big screen because if you want to truly understand the mechanics of Inception rather than simply going along for the ride, you need to see the film more than once and spend some time solving its puzzles and untangling its mysteries. I had a different purpose for each viewing and spent some serious time analyzing the art (and design) in the film.

‘Inception’ means the beginning or creation of something like a fantasy dreamscape or immersive installation. Scenes in the film look like M. C. Escher’s work set in both real and alternate worlds. The plot blurs realities, captures the imagination, and invites viewers to explore our interpretations of what is real or not. Christopher Nolan has found a way to captivate audiences using contradictory sets and defying acts of gravity that are awe-inspiring. Several moments captured my attention and made me more aware of my own thought process regarding paradox in contemporary art.

A paradox is not a conflict within reality. It is a conflict between reality and your feeling of what reality should be like.

— Richard Feynman

The film centers on Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio) and his team of extractors, forgers, and architects who go on missions to infiltrate victims’ minds through dreams and to steal important information. In one dream sequence, Arthur (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) uses the Penrose stairs to show Ariadne (Ellen Page) how to disguise the boundaries of the dreams she built as a novice architect. From a certain perspective, the staircase appears to climb or descend infinitely, but look differently and you can see they cut off abruptly. Arthur calls this “paradoxical architecture.”

Between viewings one and two, I learned that Ariadne, the architect, is also the name of a character from Greek mythology who guides Theseus, the hero, from a maze. Eames (Tom Hardy), the forger, shares his name with seminal designers/architects Charles and Ray Eames, who made the celebrated short film, Powers of Ten, about the magnitude of the universe. The name Cobb is thought to come from Jacob, who, when fleeing from his murderous brother in the biblical book Genesis, dreamed of a ladder to heaven.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0fKBhvDjuy0]

I was amazed at how art was used to illustrate the plot and alluded to broader concepts in our society. In addition to the Penrose stairs (Escher), one brief scene features the torn visage of a Francis Bacon portrait on a wall. In another scene, the face of Cobb is shown as contorted, emerging in slow motion from rushing slabs of water, like the tortured faces in several of Bacon’s famous works. We are provided with clues to the main character’s tumultuous inner struggle. Paradox and the dream logic of Inception pays homage to the surrealists and symbolist artists of the past. Relatively obscure artist Austin Osman Spare (whose work is not featured in the film) developed “idiosyncratic magical techniques including based on his theories of the relationship between the conscious and unconscious self.” Spare’s proto-Surrealist art brings to mind the twisted, sometimes grotesque art of Francis Bacon that complements the film’s plot.

In his book Towards an Immersive Intelligence Joseph Nechvatal, a post-conceptual digital artist and theorist writes,

For Spare, and I agree with him here, there are no “levels” or “layers” of consciousness, and no dichotomy between the “conscious” and the “unconscious.” There isn’t even a clearly definable boundary between “consciousness” and the “object of action” and “situation.” There is only a depth or thickness of self-awareness, from the thinnest film of near being, where we engage in pure desire/instinct driven towards action, to an opacity so paralyzingly thick that it induces catatonia. The point of automatism is that the more spontaneously we act, the less self-conscious we are.

Inception is part of a tremendous artistic/cultural paradigm shift, or as Nechvatal calls it, a viractualist zeitgeist that “signals a new sensibility emerging in art respecting the integration of certain aspects of science, technology, myth and consciousness — a consciousness struggling to attend to the prevailing contemporary spirit of our age.”

Plus Hans Zimmer’s film score is amazing!