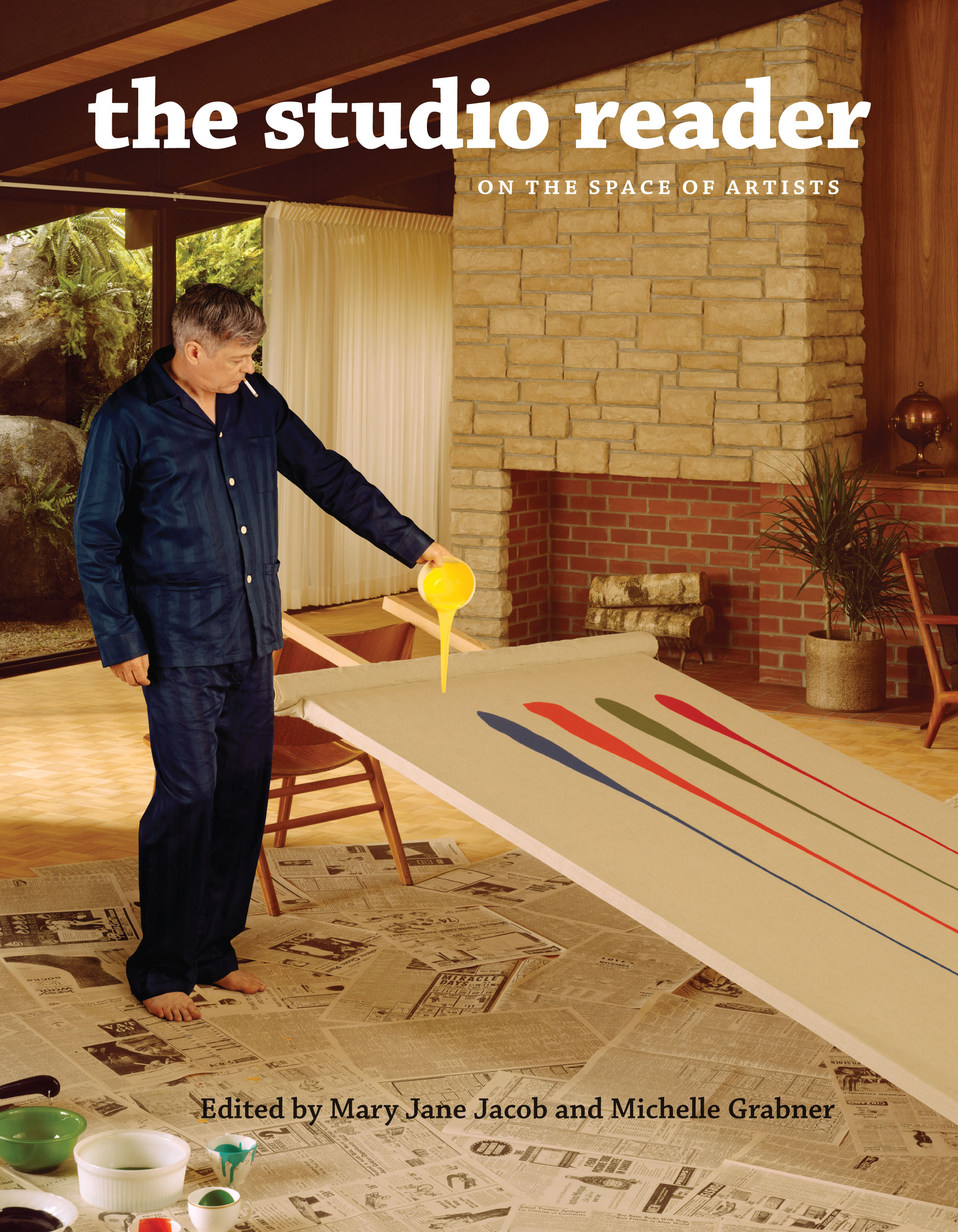

"The Studio Reader: On the Space of Artists," 2010. Edited by Mary Jane Jacob and Michelle Grabner. University of Chicago Press, 2010. Cover illustration: Rodney Graham, "The Gifted Amateur, November 10th, 1962" (detail), 2007. Courtesy the artist, Donald Young Gallery, Chicago; the Rennie Collection, Vancouver, Canada; the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and the University of Chicago Press. Design by Matt Avery.

The Studio Reader: On the Space of Artists is the kind of book an artist would eat up in a single sitting. It is about the STUDIO — the spaces of artists. Edited by Mary Jane Jacob, executive director of Exhibitions and Exhibition Studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and Michelle Grabner, artist, writer, and founder/director of The Suburban artist-run project space in Oak Park, Illinois. In its own words:

The Studio Reader pulls back the curtain from the art world to reveal the real activities behind artistic production. What does it mean to be in the studio? What is the space of the studio in the artist’s practice? How do studios help artists envision their agency and, beyond that, their own lives? This forward-thinking anthology features an all-star array of contributors, ranging from Svetlana Alpers, Bruce Nauman, and Robert Storr to Daniel Buren, Carolee Schneemann, and Buzz Spector, each of whom locates the studio both spatially and conceptually—at the center of an art world that careens across institutions, markets, and disciplines. A companion for anyone engaged with the spectacular sites of art at its making, The Studio Reader reconsiders this crucial space as an actual way of being that illuminates our understanding of both artists and the world they inhabit.

This book dissects the notion of the studio space and takes you on a journey of discovery. If you’re an artist, when you are done with it, you’ll feel the urge to get up and put it to work by re-orienting yourself in your familiar surroundings. If you’re a curator, a critic, or someone who indulges him/herself in studio visits regularly, The Studio Reader will inform your visits both physically and intellectually.

It is a useful tool that got me thinking quite a bit about the kind of artists’ studio visits I do here, as well as my about own studio space in Athens and the way I utilize it. In 2009, Inside the Artist’s Studio set out to discover where some of today’s art is being made. A book like The Studio Reader takes us forward on our quest.

So I have The Studio Reader in hand, back in a familiar place which almost feels like home – the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and specifically the Summer Studio residency program at the Sullivan Galleries, where I’ve been an artist-in-residence for the past two months working on a research-writing project.

The Summer Studio occupies a vast, open 20,000 sq. ft. space on the 7th floor of the Carson Pirie Scott building in downtown Chicago. The truth is that it is not the work itself that activates the Summer Studio, nor the “stuff” that fill up the space, but it is the intellectual wealth each of us brings into this communal setting. And that became evident as I studio-visited my peers throughout this two-month period. Artists do have a creative aura that’s manifested in physical space, and the space one inhabits is determined by one’s own creative ambitions or limitations. So how much room does an artist’s creative energy take and how does a residency program achieve creative balance within such a space? Well, that’s the challenge at hand.

Assistant Curator of the Sullivan Galleries Kate Zeller tells us more about the program and the way in which the studio boundaries at the Summer Studio were being pushed all summer long. In addition, she discusses the Process in Product: Work from Summer Studio exhibition (August 28 – October 2), best described as an open invitation for rethinking the “studio” in its entirety.

It is my pleasure to end the summer in the company of Mary Jane Jacob, Michelle Grabner, and Kate Zeller.

Georgia Kotretsos: Within the first few lines of The Studio Reader preface, your words speak of a condition that sum up the essence of the artist’s studio: “Even when the making is not so visible, it is always present.” Is it that “presence” that Tehching Hsieh is exhausting by keeping a studio space without having made any kind of art for over a decade as we read in Barry Schwabsky’s essay, The Symbolic Studio?

Mary Jane Jacob: When I said that “the studio is more than a physical place and even more than a mental space; it is a necessity of being,” I intended to convey that making art is an omnipresent thing; it works in consciously, semi-consciously, and in unconscious ways. It is always just below the surface, if not right there — in the head and hand. Yes, one can also think of this as non-studio practices that are less material and in The Studio Reader, we have such discussions of Tehching Hsieh or Kimsooja’s thought that her body is her studio. But it is also true for the painter, the sculptor, the printmaker, and we could go on with this list; it is not media specific.

How we locate an idea for art, a solution to an artistic problem, and especially the development of a work and of an ongoing practice is by living art — and this happens in the very being of being an artist. So when I speak of consciousness, I mean that we bring to our work a certain perception and mindset, and that also is present in our life. The relation of art and life is not just a 20th-century, modern, or avant-garde position; it is an essential art condition. Cultivating a deep and wide consciousness is important to many artists because, then, that just-below-the-surface state can be called into operation, seamlessly, and with this openness or permeability, a natural flow can occur that can contribute to the making of art in the studio that we take on our back.

GK: I appreciate an introduction that offers insight and a cohesive historicity on a subject, such as the one you wrote about the studio in The Studio Reader. Your closing sentence — “Critical, ironic, sentimental, and practical, the practiced place of the studio is no longer the fixed space of inspiration that Poussin laid eyes on four hundred years ago” — wisely makes room and gives reason for the rest of the book to unfold. So, what is the studio today? What does The Studio Reader tell us?

Michelle Grabner: I believe that the idea of the studio today is unambiguously foundational to the complications and contradictions of contemporary art practice.

At its most pragmatic, it is simply a necessary space of production and display. After researching the multitude of shapes and forms comprising the contemporary studio, they are no more fascinating than oil stick, video, clay, or canvas: the studio akin to a medium. However, the studio can also be a subject. And this is where it gets interesting and I hope The Studio Reader points to conditions in contemporary art production that can be sussed out through the lens of the studio.

For example, the many artist’s contributions to The Studio Reader are intriguing and insightful accounts into day-to-day studio engagement, yet it is only in their collectivity that one can start to assess how the space of production, invention, creativity, and meaning are being culled by artists today.

I think one of the most interesting disagreements in contemporary art exists between the totalizing embracement of the studio and art’s democratization: “People just make things. And so I don’t know whether it’s so necessary to ‘reveal’ anything anymore,” writes Cory Arcangel. With a swift retort, Houston-based critic Mary LeClere writes, “The question isn’t whether it’s art, but whether it needs to be. Why hold onto the name if it no longer refers to something that has a cultural, and therefore shared, meaning?”

So why the need for studios? Here within lies a complex web of contradictions that configure contemporary art and culture. The contemporary studio lays the foundation for new research into those long disparaged notions of authorship, talent, and métier.

GK: Since July 1 at the Summer Studio residency program — within the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, within the Sullivan Galleries, within individual open studios – there is art-making taking place. Besides the obvious Russian doll effect, do the conditions of the program push the studio boundaries further and if yes, in what direction?

Kate Zeller: To me, the Summer Studio activates in practice many of the conceptual arguments regarding the nature of the studio in contemporary practice, as presented in The Studio Reader. As the essays in the text examine and upend romanticized notions of the studio as the private site for autonomous production and reconsider ideas of a conventional studio, the Summer Studio program requires its participants to confront such notions in their daily practice. The physical configuration of the space itself already disrupts the idea of studio as private space. None of the 19 studio spaces have a door, let alone four walls. Each has a least one side completely open into the gallery, allowing for all passers-by to have a glimpse into their workspace. Many of the studio spaces even include tables that serve as links between walls and shared work surfaces for the artists. Thus, the physical layout of the studios themselves require the artists-in-residence to consider their practice not only as something other than happening within a private, closed-off space, but to recognize how it relates to that of others. And it is the variety of practices within this residency that begin to make evident the variants in the definitions of “studio” as articulated in The Studio Reader.

But, as you mention, these individual studios situated within this internal community [comprise] just one layer of the many in which Summer Studio is a part. One that I feel most begins to push boundaries of the studio — or perhaps requires us to consider what those boundaries are and when they are present — is when we add to these layers [that of] the viewing public. At the end of the Summer Studio, the work from these residencies will become our fall exhibition titled Process in Product: Work from Summer Studio. The artists involved have been asked to present their work, their space for display, leaving up to them the details and format of the installation to be on view. It is this conflation of the site of production and site of exhibition that seems to further question the nature of the studio, but also requires response through a product. Decisions about their presentation call into consideration what it means to put such a space on view. As discussed in The Studio Reader, with essays that address installations of artists’ studios, such as Francis Bacon’s in Dublin and Constantine Brancusi’s in Paris, such displays may serve to reinforce certain myths of the relationship between the artist and the studio. While other essays present the studio as a site of attention and a state of mind, it can be questioned as to whether or not such spaces can still be considered a studio if the artist is no longer working in them. By looking at the studio through the lens of the exhibition, such queries as considered in the text are played out in practice. All involved provide their own examination of and thoughts on [the question,] what is the nature of the studio today?

* * *

Overall the Summer Studio program has had, for a lack of a better metaphor, quite the Tetris affect on my own studio/writing practice. Each block that fell filled up a gap and made a straight line, which then instantly erased itself by making room for more blocks to come. I could not have asked for anything more.

And, that’s a wrap!