I. This past weekend I visited three museums in New York City — New Museum on the Bowery, the Studio Museum in Harlem, and P.S.1 MoMA in Queens — if only to get back in the habit of looking at art after a summer of not attending many art events. At the New Museum, I saw the oddly appropriate threesome of Brion Gysin, Rivane Neuenschwander, and Bidoun magazine’s “library” of printed (and some electronic) matter crossing between Middle-Eastern and Western contexts.

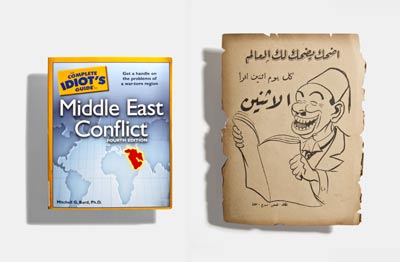

The overlapping curation of New Museum’s exhibits was especially apparent in regards to Bidoun which, since 2003, has been a beacon for symbolic exchange and cross-cultural dialogue about Middle Eastern art, and Gysin, whose work finds purchase in Middle Eastern and North African cultural traditions and aesthetics. Among the Bidoun library, one could find materials ranging from North America and European novels depicting Middle Eastern espionage, to magazines from the region tracing events of geopolitical significance. Some of the materials were totally ridiculous, such as the series of romance novels featuring a swarthy “sheik” and his scantily dressed lovers; others represented some of the most earnest, if not loving, attempts by Western writers to encounter the “other,” such as Gilles Deleuze’s and Felix Guattari’s Nomadology, Kathy Acker’s Algeria, and Jean Genet’s Prisoner of Love. Something I found particularly compelling about Bidoun’s library was its ability to focus the viewer’s attention in specific ways, and to activate critical thinking through an assemblage of materials. By spending time with the cover designs of much of the printed matter, I was offered a window into the ways that the Middle East has been imagined (and imaged) by a Western imaginary, and vice versa. I also liked that Bidoun did not attempt to explain the materials, and left explanation — and thus interpretation — in the hands of its viewer/reader.

Bidoun’s library was a nearly perfect segue into New Museum’s retrospective of Brion Gysin, the English-born polymath best known for his pioneering discoveries in cybernetics and for his invention, with William Burroughs, of the “cut-up,” the literary form that would inspire Burroughs’s novels and many literary works after Burroughs, such as those by Kathy Acker, Dodie Bellamy, and others given to collagist-appropriational writing techniques. Gysin’s work was first made known to me by a curious little book that I would strongly recommend, John Geiger’s Chapel of Extreme Experience, which chronicles the influence of Gysin’s Dream Machine, a cylindrical lighting device designed to induce hallucinogenic experiences sans psychotropic drugs through “flicker” effects (lighting effects that synch the brain’s alpha wave frequencies), upon modern and contemporary art. Some of the most fascinating connections in the book relate Gysin’s work to artists such as Tony Conrad, whose film The Flicker is a primary influence for Structuralist Cinema, as well as later day “noise” artists such as Genesis P-Orridge of Throbbing Gristle (according to a placard at New Museum, the band Gysin apparently thought best to listen to while using the Dream Machine).

Wandering through the exhibit, the New Museum’s curation of Gysin’s post-1948 career provided a moving portrait of Gysin’s encountering and taking-up of Middle-Eastern culture. Though European Surrealism provided Gysin with a foundation for art making, it was clearly Middle Eastern (and specifically Moroccan) cultural production that furnished Gysin with his greatest inspiration, if not with his most signature artistic discoveries such as the calligraphic paintings, serialist (atomist?) films, and permutational poems (poems produced through algorithmic patterning).

Also moving in the exhibition were documentary materials tracing Gysin’s longtime friendship with William Burroughs who, in a video included in the exhibit, laments that Gysin’s work was not more supported and economically rewarded in the artist’s lifetime. Among these materials were Burroughs’s film collaboration with Gysin, Towers Open Fire and a series of letters and papers responding to Gysin’s discovery of the “cut-up” composition technique. Though I have long heard repeated Burroughs’s famous dictum that language is a “virus from outer space,” I don’t think I fully understood the meaning of this phrase before encountering his letters with Gysin regarding cut-up, in which Burroughs argues for a kind of writing that will not only provide language with a new content (software), but which may actually change the hardware.

As Gysin’s and Burroughs’s friendship proves through the New Museum’s exhibition, the two friends were clearly trying to alter the way people think in fundamental ways. Through hieroglyphic, calligraphic, filmic, and cybernetic forms of language specifically, they discovered the neuro-biological-grammatical underpinnings of new forms of consciousness, a means of thinking outside of given “board books” (Burroughs’s term for the forms and mediums language had assumed in their era). This new hardware obviously spins out of particular lifestyles with which both of the artists were engaged (both were gay, both used drugs recreationally, and both were attracted to bohemian cultures), but also through an earnest engagement with submerged cultural expressions, such as those Gysin encountered in North Africa and which the artist both appropriated and transformed through his unique aesthetic practices. Gysin, like so many artists in the 20th century now coming to light, makes one reconsider the way culture translates (moves and bears across), hybridizes, and makes both appropriate and ambivalent.