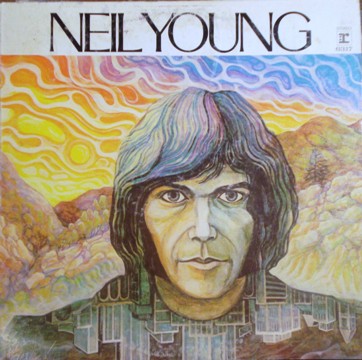

Neil Young. "Neil Young," (Reprise Records, 1968). From the writer's collection.

It was the United States of America in the cold late spring of 1967, and … all that seemed clear was that at some point we had aborted ourselves and butchered the job, and because nothing else seemed so relevant I decided to go to San Francisco. San Francisco was where the social hemorrhaging was showing up. San Francisco was where the missing children were gathering and calling themselves “hippies.”

―Joan Didion, “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” (1967)

Something monumental happened before I arrived, I knew that it had. Growing up in the late 1970s and ’80s in Northern California, I searched for clues to the past in my father’s record collection. I studied Neil Young and Buffalo Springfield album covers, committed the lyrics to Helplessly Hoping to memory, and decided I liked paisley. At 16, I hung the album cover to Neil Young on my wall. The singer’s face is rendered in watery peach, his hair streaked with purple. Behind him, golden hills tinted with pink billow like clouds. I didn’t understand what it meant ― LSD? Something to do with the Merry Pranksters? Communes? ― but I felt closer to the mystery by claiming the image.

The legacy of the 1960s and ’70s hangs in the Northern California air like smoke from a stick of Nagchampa. While the ideas and activism of those decades may have subsided, the imagery and laid-back sensibility remain. Recent years have seen a particular resurgence, as many Bay Area artists have embraced a quasi-mystical primitive aesthetic (see David Wilson’s Sun Ceremony) that harks back to this earlier era.

Gina Tuzzi, "Silver and Gold, (2000)," 2009. Acrylic on paper. Courtesy the artist.

Gina Tuzzi wasn’t alive in the 1970s, but she absorbed the era’s iconography through her parents. She digested their record collection and observed their world of custom-decorated vans and Harley Davidsons. Now nearly thirty, Tuzzi makes paintings and sculptures that express her longing for this inherited period, which she can only ever experience secondhand. By translating its imagery, she engages with its mystery and creates her own.

Raised in the coastal town of Santa Cruz, she frequently references California coastal culture in her work. In the paintings El Dorado 1989 (2009) and Silver and Gold 2000 (2009), guru-like figures with glassy eyes and painted emblems on their foreheads wear long beards of beach debris. Kelp and seaweed in shades of yellow and green, collapsible metal beach chairs, a shark’s dorsal fin, and a bright pink starfish combine to make a complete world on the man’s chin. It is part organic, part disposable culture, the meeting of ocean and shore.

Tuzzi’s MFA exhibition at Mills College was dedicated to Neil Young, and many of its pieces were named for his songs. For one versed in his music, the singer’s reedy voice might serve as a silent soundtrack to the work. We can hear his singing about knowing when it’s time to change, blue fading to black, and feeling helpless for a town in north Ontario.

Gina Tuzzi, "Rust Never Sleeps (1979)," 2009. Acrylic on board. Courtesy the artist.

The song “Rust Never Sleeps” by Young includes the line “out of the blue into the black.” Tuzzi’s painting of that name includes a figure outlined in constellations, his black face and arms emerging from a blue pool. It might be Johnny Rotten, the subject of the song, writing from heaven. Or simply a meditation on the stars. Including the album cover for Neil Young, it could be a reference to the afterlife of artistic production, which seems to find a new life in each generation.

Gina Tuzzi., "Tonight's the Night (1975)," 2009. Graphite on paper. Courtesy the artist.

Tuzzi’s drawings and sculptures of cars adorned with wigwams and domes evoke a nomadic lifestyle indicative of the California coast. Imagine surfers combing Highway 1 in search of the perfect wave, campers parked in ocean lookouts for the night, a plume of smoke rising from a primitive chimney. Imagine always being home, no matter where you are.

But Tuzzi takes this nomadic tendency to ridiculous extremes in pieces like Kickin’ Hippies’ Asses, suggesting there’s a dark side to always being able to pack up and move along. Homes are stacked upon homes upon truck bed, and a defeated sigh seems to emit from the vehicles’ sagging tires.

Gina Tuzzi, "Kickin' Hippies' Asses." Courtesy the artist.

Tuzzi does more than recycle themes and images from an earlier era. By being overt in her references and citing her sources, she is self-aware, rather than sentimental, in her nostalgia. With themes like desire and transitions, her work can even be seen as a rumination on the nostalgic tendency itself.

In my next post, I talk with the artist about the resurgence of ’70s imagery and themes in Bay Area art, her own influences, and, of course, Neil Young.