Lately I have been thinking a lot about sustainability and sustenance. Not the environmental kind of sustainability–the personal and emotional kind. Chicago’s art community is rich in relationships, but like so many other ‘art worlds’ out there, it can be a bit less bountiful when it comes to monetary compensation, feedback, and consistent forms of validation. So, for our last post on this blog for the year, I asked four longtime Chicago-based cultural practitioners–independent curator and arts educator Britton Bertran, artist Duncan MacKenzie (co-founder of Bad at Sports), Caroline Picard, an artist who runs the small but highly-regarded Green Lantern Gallery and Press, and Philip von Zweck, an artist whose work often involves project-based collaborations–a few questions about how they have sustained their own practices over time, and especially after a project has run its course. How do they stay sharp and engaged and committed over the long haul? How do they keep on keepin’ on when the going gets tough? Read on to find out what this group had to say.

Claudine Ise: Describe the work that you do. What forms has the work taken? When its form has changed, what were some of the reasons for the change?

Britton Bertran: I started my “career” here in Chicago working for a well-known and very progressive not-for-profit art education organization. It was hard and fulfilling programmatic work placing ‘teaching artists’ in mostly underserved Chicago public schools. Around 2005 I decided to open my own commercial art gallery (called 40000). One of the main reasons for doing this was jettisoning the funk of non-profit work and diving in to the wild world of working with artists for profit (theirs and mine). Three years later, and a month before the great economic collapse of 2008, I closed the gallery. To this day, I am simultaneously extremely relieved for shutting down but will also ultimately regret doing so. Currently I am working for another Chicago-based art education not-for-profit with a more encompassing, less intense mission that is equally challenging. It’s very satisfying and comes with a real live paycheck. Interspersed with the jobs I have had in for the last 4 years or so, I have also had a secondary career as an independent curator and instructor in the Arts Administration department at The School of the Art Institute.

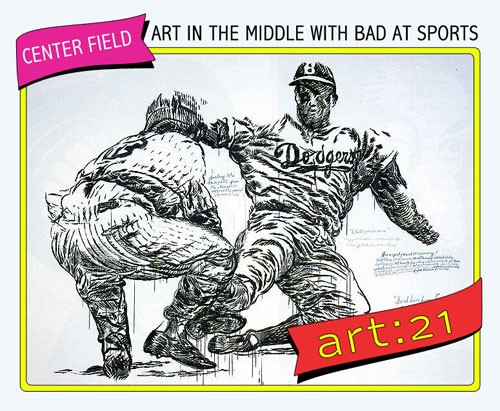

Duncan MacKenzie: The way that I work now is collaboratively, sometimes that means working on the “Bad at Sports” project and at other times that work is with an artist named Christian Kuras on an object and image-based practice. As a young artist, I was trained in several really active communal print shops, a series of film sets and a small graphic design firm. Those experiences left me with a strong drive towards communal working and a need to share broadly both the authorship and the result. This is a very different way then the traditional “heroic artist” locked in their studio wrestling with a canvas. I don’t love spending my time all alone working through a series of problems and puzzles which I’ve situated for myself. I like and need the energy colleagues bring to projects.

Caroline Picard: For the last six years I have been running a non-profit gallery and press called The Green Lantern. During that time I have continued to work independently as an artist and a writer. I think these projects inform one another–in many ways I’ve thought about the Gallery and the Press as being significant influences on my own work; particularly when the space was in my apartment, I came to think of it as a kind of studio-research. After five years the city shut down the project because I did not have, nor could I acquire, a business license (as a result of zoning). Last September I opened a second storefront space which will close in January of this year. As part of this second plan, I was trying to put together a business model which would sustain the non-profit gallery via a for-profit cafe/bar/bookstore/performance space. I couldn’t find that space, and after a continued accrued cost had to close up shop. The Press will continue and I’ll continue as its primary editor. We also have a very cool on-line indie-lit bookstore.

Philip von Zweck: From the early 90s (as a student) until relatively recently most of my projects involved either producing a form for others to fill and/or making projects for a non-art audience. For 15 years I produced a weekly radio program of live performance and sound art recordings, and I co-founded the radio art collective Blind Spot; I have an ongoing project called Temporary Allegiance which is a 25 ft flag pole that anyone can sign up to fly anything they want on for a week at a time; I ran a gallery in my living room for 3 years; for my museum show a few years ago I made a chain letter and mailed it to the museum’s mailing list. There was a set of politics I was really guided by, and adhering to them eventually caused me to feel distanced from my own practice. So a few years ago, I begun showing paintings. I’ve always painted and drawn but didn’t show them because it didn’t fit in with the other projects and those took precedence. I wouldn’t say that I have abandoned the previous set of politics; it’s just that I’ve come to a different way of thinking about them and my role as an artist.

CI: What are some of the happiest and/or most satisfying period/s of production you’ve experienced thus far, and what made them so? What were some of the low points? How did you pick yourself back up again and find the where-with-all to start fresh?

Britton Bertran: The opening night of the first exhibition I put together for 40000 was the happiest most satisfying 5 hours of my professional career. A completely fulfilling experience that squashed a good six months of the most terrifying anxiety I’ve ever known. Quitting my job to start my own business without any financial security or previous gallery operating know how was also one of the stupidest things I have ever done. Looking back now – part of that happiness was pure obliviousness, but seeing three hundred people come and pretty much stay that night had a profound affect on me.

My low point was realizing how screwed I was by the overall economic situation. Either I was too arrogant to think I would never have work, or I thought I was just plain invincible, but [the period after closing 40000] was the most incredibly depressing and scary six months of my life. Part of my problem was the fact that I had convinced myself that I had paid my dues and that a job, in the art world please, should just come waltzing my way, take my hand and whisk me off to that thing called adulthood. It was around this time (as I was selling my lovingly collected vinyl records in order to eat), that I realized I had built a solid network of individuals that could help me. Pride swallowed, I groveled, professionally, and just asked. Within two months I was working.

View of opening reception for "Artist Run Chicago" at the Hyde Park Art Center, curated by Britton Bertran and Allison Peters Quinn

Duncan MacKenzie: All of the most recent satisfying moments were times in which I felt very connected to our projects and felt like others were as connected to the result. One of the most amazing experiences, recently, was doing “Don’t Piss on Me and Tell Me its Raining” at Apexart in New York. What made it such a delight was to know and have tangible proof of what our project is meant to the hundreds of people who been involved in its production. It was amazing to feel so intimately connected to so many other artists.

The low points for me are almost always the same. They are the moments that I feel like the art world is either just like a clique-y, bitchy, high school popularity contest or like a fashion Mall and all the things we make are just as disposable as this week’s “Entertainment Weekly.” They are always the moments that make me feel like we are not a community but a bunch of humans who represent opportunities to each other and should just be used as opportunities. So I guess they are moments when I feel disconnected and disregarded. Thankfully it is as easy to get out of as picking up the phone and reaching out. All it takes is a little reminder that we all feel alone, awkward, and like no one cares, but every one of us does this because we know how meaningful it has been to us and that we still share in it.

Caroline Picard: High points: I think my consistent favorite moment will always be the point an audience (of whatever sort) has settled into attendance–when the program has begun and the work is done–whether that’s the work of an administrator, or a producer. For me, those moments resolve the otherwise insatiable existential question (in my mind) of what art is for because art is precisely for that moment. My other favorite moment is the deep concentration that happens when I am working on my own, whether writing a piece, or painting, or editing.

Low points include: Discovering typos in my writing–particularly if those typos point to some never-before-recognized ignorance–what are they called, lacuna? I think [Green Lantern’s exhibition space] closing a second time is another one of those moments, despite my realizing that there was no specific failure involved–I am proud of what the last six months have brought, thrilled that I got to work with such great people and participate once more with the Chicago art community. Yet, I am conscious not fulfilling the larger, albeit abstract, vision I had undertaken. As far as how to get through that stuff–I don’t think there’s any trick beyond being patient and humble and adopting a sense of humor (I like to think of my consciousness like my grandmother–if it/she shames me I make a slew of jokes which, more often than not, work because they fail).

Philip von Zweck: The times when I am the most productive — and therefore happiest — artistically are generally times when everything else is going right; the times when I’m neither broke or pulled in a thousand directions (from taking on too many jobs or commitments), when I’m in good health, relationship, community, etc. When those things start going wrong it is really hard for me to make work, it becomes a feedback cycle- things not going well leads to being bummed out, which leads to not making work, which leads to being bummed out, which leads to….

Perhaps the lowest point came from doing a project in which I was treated poorly by the presenting organization. What should have been a great experience seriously made me never want to make work again. How did I pick myself up? I didn’t have a choice, I had already committed to do another project, and that one went swimmingly, actually way better than expected and that was enough- not that the previous experience has left my mind, but I’ve mostly moved on.

CI: All of you are engaged in practices that involve lots of other people (though I know that several of you maintain studio practices, too). I often think through my own personal quest for ‘sustenance’ in terms of introversion versus extroversion: sometimes, we recharge our energy by spending time with friends and collaborators, other times by being alone. So, how do you recharge — and how does it help you sustain those practices you most want to engage in?

Britton Bertran: The relationship between institutional and individual memories, as a conundrum, is fascinating to me – and worrisome. In order to combat that, I have made a real effort to reflect on my personal and professional experiences (process) in order to better inform my future (product), especially when it comes to being a part of the immediate art world around me. I also believe it has to be more than just taking pictures. The essential part that I concern myself with is finding ways to reflect, edit, and share those experiences. As official memories, of the institutional kind, seem to be becoming more and more overwhelmed by the collective desire for the next memory, harnessing something that I would call “The Slow Memory Movement” might become more essential. This Slow Memory Movement (akin to the Slow Food Movement) would emphasis the personal importance, or pleasure, of remembering and the sustainability of its impact on oneself. (I also have been reading as much post-apocalyptic science fiction as I can get my hands on which, beyond the pure entertainment factor, does wonders for the reflective process).

Duncan MacKenzie: Recharge? I read crime novels in which wizards solve crimes, and comic books. It is the source of a small amount of shame, but a couple of years ago I felt like everything in my life was connected to art production and I needed to find something that I was not going to try and plug back into an art world. Now it seems likes wizards are the order of the day and I am looking for novels about dinosaurs solving crimes.

Caroline Picard: Top 5 Ways to Recharge would include:

1) Deep and quiet thinking about a particular subject which is engaged through writing/visual work. The act of making something discrete–something very often totally “useless”–then makes me very happy.

2) Being with friends (of course), art-friends and non-art friends both.

3) Making Jokes, which I think I too easily forget. Making Jokes should probably be no. 1.

4) I have to admit, though I will immediately disown this, I also recharge watching some sort of television-thing, preferably an episodic serial drama.

5) Making non-art things like food. Or dreams.

Philip von Zweck: I don’t ever consciously think “I need to recharge” but I spend a lot of time alone and- not that I ever set out to not work on art, but really- it is very hard for me to not work on stuff. Sometimes this can be recharging, working in the studio can be a good antidote to a day at the job. But I guess for me it would be spending time with friends. A lot of ideas and projects come out of just hanging out, I think this is why I’ve done so many collaborative and social projects, they are both rewarding and rejuvenating.

CI: Thank you all so much for sharing your experiences and ideas with me and with our readers at art:21 blog.

Please Note: This roundtable discussion is an excerpt from a lengthier text. The full text will be available on www.badatsports.com.