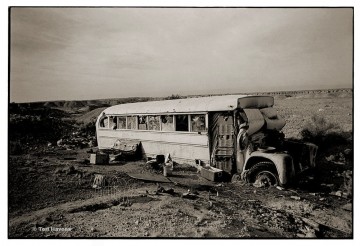

Teri Havens, "Richard's Camp," 2006, from the series "The Last Free Place." Toned silver gelatin print.

Guest blogger Kerim Aytac is filling in for regular columnist Ben Street this month while he makes his millions. — Ed.

It’s hard to see the work of emerging photographers hung in London. There are relatively few dedicated photography galleries and even fewer showing the work of fresh talent. To emerge as a photographer or photographic artist is indeed a complicated thing. Where does one emerge to? The art world now purports to accept photographic practice as part of its remit, but perhaps understandably, only a particular style or type makes it through. Compared to our European neighbours, France and Germany in particular, or our American cousins, the desire here is very small for those who cannot access the art market. The resulting polarization is a well-tread truism: Photography as Art or Art as Photography. Practitioners who occupy the middle ground seem to emerge elsewhere. The only other method by which to be successful, it seems, is as a genre-specific virtuoso; the best in fashion, the best in portraiture, and so on. Photojournalism, bar the work of a few genuinely inventive die-hards like Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, has lost cultural credence, falling off the tightrope it walked for so many years between form and function. As a result of all this, the main way that large sections of the British public get to access photography is when there is a Prize.

The Prize is, as curatorial concept, a comforting thing for the visitor. It is reassuring to know so many artists are baying for one’s attention. The visitor is encouraged to think: try hard, work hard, and one day, maybe, if I have the time and have nothing else even marginally more interesting to do, you might be worth an acknowledgement in the form of my attendance. The foregrounding of the gate-keeping process that cultural institutions routinely employ allows the public to feel its affections are being earned as opposed to foisted upon. In London, both the Taylor-Wessing Portrait Prize, held annually at the National Portrait Gallery, and the also-yearly World Press Photo held at the Royal Festival Hall, are always big hits. It might be cynical to suggest this is partly due to the fact that these reward the efforts of those working in genres closely aligned to what photography seems to be for: functions rather than concepts. The Turner Prize of fine art photography, the Deutsche Börse Photography Prize is consistently considered contentious and comprehensive, but only rewards those already established and blue-chip. Perhaps the Terry O’Neill Awards, a new(ish) prize in a new(ish) space showing new(ish?) work, will break the mold and provide a forum for those emerging to gain exposure.

Set up in 2008 in honour of one of the surviving photographic legends of the Swinging London of the sixties, the award invites submissions in all genres, including Fine Art as a type in itself, so long as they are “dynamic images that portray a compelling narrative.” The judging panel consists of both photographers and specialists as well as Mr O’Neill himself. Such loose criteria make for an unpredictable selection in an interesting show, held for the first time this year at the consistently brilliant Hotshoe Gallery in Farringdon, London.

It is a fascinating process to try and engage with work both in terms of quality and style. Photojournalism is better suited to storytelling than landscape or fine-art work, so shouldn’t the practitioners of the latter be rewarded by virtue of having met the challenge? Teri Havens, for example, whose project documents the inhabitants and landscape of Slab City, a squatter’s community in the Southern Californian desert, constructs her narrative through mystery and enigma. Using available light, black and white and traditional printing methods, she manages to create a distinction between seeing and looking. The scraggy misfits she photographs are interesting, beautifully human outcasts who retain their dignity under her lens. They are not represented as exotic or “other” in a way that might warrant mainstream media exposure, but different enough to make us question our own modes of existence.

This is unfortunately not the case for Laura Pannack‘s work, whose curious emptiness might be seen as an asset by some. Posing members from British nudist subculture in the way that she does, presents them as surface, devoid of an underlying philosophy that must surely motivate their commitment to the cause. The sitters are still, vacant. So cool an approach serves to divorce the viewer from the subject and is reinforced by the glossy color aesthetic. I could well have misjudged, as the panel awarded Pannack third place.

Kenneth O’Halloran‘s terrific Tales from the Promised Land depicts the cruel disintegration of the Irish housing boom. To use his own words: “‘Zombie’ hotels, ‘ghost’ estates, and mothballed apartment blocks mock the hubris of another era.” His photographs of abandoned constructions are both witty, heartfelt, and juxtaposed with fragments of promotional imagery that crystallize the corporate, suburban dream that drove the boom. The landscape of investment. Indeed, they take on an almost archaeological, as if this is the iconography with which future generations will have to piece together our civilization, come the floods.

The winner was Sebastian Liste with his series Urban Quilombo. Documenting the poverty of the inhabitants of a slum within a former chocolate factory in Brazil, the project is a triumph of style over substance. His high-contrast black and white images, all canted angles and confrontational verisimilitude, are undeniably powerful but lack a real connection with the people he claims to care for. This unfortunate community is made up of the “exotic.” They are curious unfortunates whom we are invited to contemplate rather than empathize with. Liste’s artist statement on the awards website is a long list of other awards and scholarships recently received, so a bright future beckons, and if Sebastio Salgado’s (probably a key influence here) career is anything to go by, Liste will do some very important work. I can’t help feeling, however, that the panel had fallen into the mistake judges often make when judging photojournalism: rewarding a photographer for his or her ability to access the remaining areas of misfortune that haven’t been exposed to death on the rolling news networks, rather than the skill or subtlety with which images communicate. Liste’s work shouts the loudest, is the clearest in terms of its meaning, and perhaps that’s what needs to be done, but put alongside the gracious compassion of Havens’s work, or the dry wit of O’Halloran, it becomes deafening. Maybe documenting the West is a lost cause.

As prizes go, this is a noble venture. I would hope that, with time, these awards will contribute to the creation of a photographic culture in Britain that can move beyond the easy extremes of genre and art. The beauty of the medium is that it cannot be pinned down that easily. Walking through this show, I felt that I needed to earn it.

Kerim Aytac is a visual artist and lecturer in Film Studies, based in London. He’s not sure where he’s from. He is one of the team at Intervention Gallery.