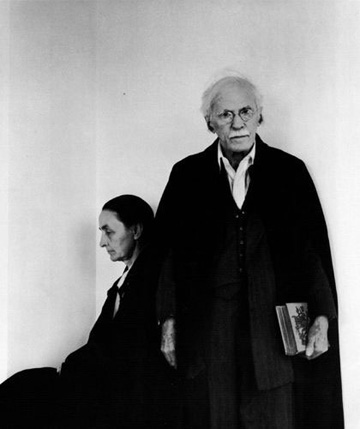

If deprived of intimacy—without the closeness of another human’s body and touch—a human child has little chance of survival past infancy. In societies where the majority of people have all their basic needs met—food, potable water, clothing, shelter—our need for intimacy, both physical and emotional, remains the one essential need that neither charitable organizations nor public welfare programs can satisfy. When it comes to the production of art, we often think of artists’ intimate relationships in conflicting terms—supportive and nurturing, as in the case of Henri Matisse’s mother, who gave him his first paint set and encouraged him to pursue his artistic talent, or destructive and suffocating, as exemplified in photographer Alfred Stieglitz’s attempts to dictate the direction of his lover Georgia O’Keefe’s career and mold her development as a painter.

We are used to thinking of intimacy in these dualistic models, both in the sense of it being either constructive or destructive, and in the sense of it existing only between two people. But the relationship between a pair is only the basic unit of intimacy. Intimacy exists between groups as well, within families and communities of friends, neighbors, or colleagues, giving rise to self-defined, self-identified collectives. Art schools and artist colonies can also provide intimate environments that may either nurture or inhibit creativity. At the Black Mountain School in North Carolina, European and American modernists were brought together to pursue common creative goals and teach new generations of artists to think differently about their work. Max Beckmann’s poignant Les Artistes mit Gemüse (Artists With Vegetable) depicts an artistic community lost as a result of war. Depicting himself and four friends, from whom he was separated by World War II, at an imaginary dinner party, Beckmann attempts to recreate the intimacy rendered impossible by the war’s violence, reuniting himself with his friends within the space of the canvas.

Jasper Johns, "Souvenir," 1964. (Copyright Jasper Johns; licensed by VAGA, New York, NY/Smithsonian)

Reading Holland Cotter’s review in the New York Times of the National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition, Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture several weeks ago, I was reminded that intimacy has greater consequences than the simple satisfaction of a basic human need. Describing the museum’s choice to pull David Wojnarowicz’s video piece from the show in capitulation to political pressure, Cotter writes that doing so was an attempt to keep the political controversy from distracting from the curators’ primary point in the exhibition, “namely, that the work of gay artists was fundamental to the invention of American modernism. Or, put another way, difference had created the mainstream.” This comment reminded me that because intimacy is an inherently social need, it is also socially regulated and therefore vulnerable to political and legal regulation as well. Thus artists’ intimate relationships, the ways in which they satisfy these needs, can both impact the way we interpret the art that we see and also determine the art that we are allowed to see, whether by institutional actors, by artists themselves, or by those with whom they are intimate. Cotter points out the significance of not only the mere presence of works by Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns in this exhibition, but also the way in which the pieces are installed, paired side-by-side, in the gallery. Both artists were publicly silent throughout Rauschenberg’s lifetime regarding their relationship due to the social taboos surrounding homosexuality; Johns’s allowance of his work’s inclusion in this show demonstrates the extent to which American society has changed over the past few decades.

As the social and cultural consequences of the museum’s act of self-censorship continue to reverberate throughout the American art community, we cannot help but be reminded of the truism, perhaps rather antiquated in 2011 but clearly still relevant, that the personal is political—including that most personal of human experiences, the satisfaction of our need for intimacy.