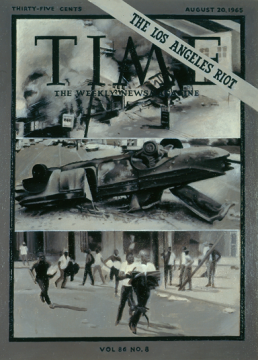

Vija Celmins, "Time Magazine Cover," 1965. Oil on canvas, 22x16 in.. Private Collection c/o Ms. Laura Bechter. Courtesy LACMA.

Last Saturday, March 19—the day that the US began air strikes in Libya—I passed an anti-war demonstration while driving to LACMA to see Vija Celmins: Television and Disaster, 1964-1966. It was a few minutes before I realized that it was also the anniversary of the war in Iraq and these protests had been organized across the country on March 19 for the past eight years. I almost considered canceling my obligations for the day to indulge my political leanings and join the throngs of protestors.

Protestors in Los Angeles on March 19, 2011. Photo by Travis Wilkerson, image courtesy answercoalition.org.

I rationalized my decision to continue with my day as planned, telling myself that I would be showing solidarity by visiting Celmins’s show. Each of the 20-odd pieces in the exhibition capture moments of either horrific destruction or potential destruction—frozen first by photography, and then re-captured by Celmins’ careful hand. The intersection of art and politics is rarely successful, and often artists who attempt it fall into the realm of didacticism and propaganda, or worse, aestheticizing violence. But Celmins’s images of conflict and destruction, painted during the Vietnam War, avoid these pitfalls while retaining their own kind of force and power.

The works were all completed while Celmins was a graduate student at UCLA, before she began creating the quiet, meditative surfaces depicting night skies, spider webs, and horizonless seascapes for which she is known. The subjects range from a brooding rhinocerous to a smoke and flame-engulfed beach, and almost every painting is rendered in the subdued monochromatic scheme that characterizes most of Celmins’s oeuvre.

Vija Celmins, "Hand Holding a Firing Gun," 1964. Oil on canvas, 24 x 34 in. Joan and Jack Quinn. Courtesy LACMA.

Perhaps most captivating are Celmins’s paintings of warplanes. Based on images from library books about World War I and World War II, German Plane, Flying Fortress, Burning Plane and Suspended Plane all feature a single airplane hanging in space. Although the latter two fighter planes are shown breaking apart on the brink of explosion and German Plane is adorned with the Swastika symbol, which now seems to be the universal symbol for ultimate violence, the images all feel strangely placid.

When Celmins discussed Suspended Plane in Season 2 of Art in the Twenty-First Century, she contemplated the source of the stillness in an image that some might see as dramatic. “It came out of me painting objects, single objects on the still life, and then I sort of shifted… to painting objects that were found in photographs that were no longer objects now but machines. Mostly airplanes. I think of them as sort of still lifes still.”

Vija Celmins, "Suspended Plane," 1966. Oil on canvas, 23 3/4 in. x 34 3/4 in. Courtesy SFMOMA.

Yet Celmins maneuvers these images into the realm of the placid still life without beautifying the suffering and violence surrounding them. Seeing Celmins’s warplane paintings immediately brought to mind Gerhard Richter’s Düsenjäger, painted almost at the same moment, in 1963. Richter’s painting of the fighter jet, while also painted with a limited palette and clear reference to photography, is far more kinetically charged. Celmins’s paintings place the viewer slightly above the planes, while Richter’s jet tilts menacingly to the side, sending the viewer below them.

Both artists grew up in Europe during World War II. A native of Dresden, Germany, Richter and his family were active in the Nazi Party, while Celmins, born in Latvia, endured attacks from Germany throughout her childhood. Given their respective biographies, it is easy to fall into the trap of reading Richter as the aggressor and Celmins as a victim. Yet there is a distinct sense of aggression in Richter’s work that never arises in that of Celmins.

Gerhard Richter, "Düsenjäger," 1963. Oil on canvas, 51 7/8 x 78¾ in. Image via Christie's.

In fact, Celmins imbues the images with such placidity that she disempowers her subjects. In her Art in the Twenty-First Century segment, she explained how the warplane paintings relate to her own history. “I painted this in the middle of the Vietnam War. I was sort of remembering the planes when I was in Europe myself in 1944, just a small child. I remembered the airplanes. I’d never seen one of course but I heard them, you know?”

Vija Celmins, "T.V." 1964. Oil on canvas, 26 1/4 x 36 in. Courtesy LACMA.

In describing her more recent work, Celmins speaks of finding emotionally potent images and “neutralizing” them. Perhaps the forces of her earlier practice are not so different. While seeing disaster can be devastating to the psyche, there is nothing more horrifying than a bogeyman with no face. But by depicting the source of those noises that had terrified her as a child, Celmins renders them impotent. Repicturing mass media images of war in modestly sized handmade monochromes, Celmins neither glamorizes violence nor explicitly condemns it. She simply strips it of its power. And this gesture, in and of itself, is incredibly powerful.