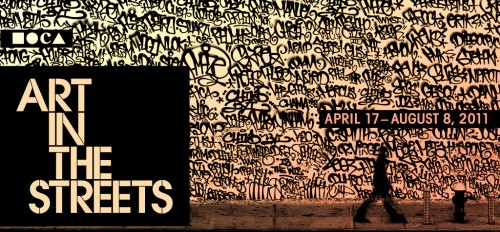

While in California, I made a pit stop to see Art in the Streets at MOCA in Los Angeles. Art in the Streets is the first major historical exhibition of graffiti and street art organized by a major American cultural institution. Opening this year in LA, it will travel to the Brooklyn Museum in 2012. Days after opening to the public, the LA show came under fire from local law enforcement for spawning a rash of tagging near the museum. Public areas outside the venue have become targets for taggers who want to leave their mark. The museum says this response was anticipated and will be cleaned up. In a show of support, local street artists say the exhibition is giving a boost to neighboring businesses. The overall opinion in the local art community is that the controversy surrounding the show is a good thing because it focuses attention on the lack of creative outlets for artists in the city. On the other hand, many street artists are still questioning the decision by MOCA director and show curator Jeffrey Deitch to whitewash a mural by Italian artist Blu late last year. These events and debates pose questions of whether or not graffiti and street art have a place in the mainstream art world, or even in the grand narrative of art history. My affirmative responses to these questions will be addressed as I go along.

To walk into the Geffen Contemporary in LA’s Little Tokyo neighborhood is to enter the realm of pure unadulterated street art. It is also to experience what is now a thriving knowledge culture that merges specialized forms of representation: alphabets, drawings, paintings (graffiti), films/videos, pop culture artifacts from times long past, and so on. One word that came to mind after seeing the show was “overwhelming.” I was struck by the urban detritus, hip-hop bricolage, bright colors, lights, and sounds in the various galleries on the lower level. This work emerged from a culture that has grown through the creation and application of art forms that are heavily layered, rich in imagery and metaphor. Most of the artists selected for Art in the Streets have used urban environments as their canvas. Many had been excluded from displaying their work inside of major art museums and galleries and opted to create their art outside of the doors that were previously closed to them. In an interview for Juxtapoz magazine the curators of this landmark exhibition, including longtime supporter Jeffrey Deitch, discuss this development:

[I] love this difference between graffiti and street art from more mainstream museum art. If you get into a museum or gallery in that world, it is after this long process of going to the right art school, with the right teacher, the right assistant job for a famous artist, the right recommendations, a review in the right art magazine, and finally the endorsement, and you can then show your work in a little gallery. We are dealing with artists that had nothing to do with these obstacles.

Lee Quinones's tribute to the modern graffiti pioneers at MOCA's Geffen Contemporary in Los Angeles, 2011.

Works by well-known modern graffiti and street art pioneers such as Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf, Lee Quinones, and Banksy are mixed in with contributions by underground and emerging artists, including locals from the Los Angeles area. The installation by female street artist Swoon is ethereal and I was amazed by the fluid, calligraphic style of LA-based Mexican artist Mister Cartoon (Mark Machado) who painted a “pimped-out” ice cream truck and automobile. Two other cars by Haring and Scharf are also on display. Work by Fab Five Freddy and Martha Cooper are a part of this history. On the upper level is a timeline of this artistic and cultural movement, beginning with the emergence of tagging in New York City and Philly, through Chicano and “cholo” graffiti of the 70s, and exhibitions in mainstream NYC galleries in the 80s. The journey also takes visitors through the intersection of these art forms with punk and skateboarding cultures, including a few of Raymond Pettibon‘s Black Flag flyers. The show features the Wild Style graffiti movement that hit New York City’s subway cars in the 70s and 80s and the Do It Yourself (DIY) movement that includes work by Barry McGee and Margaret Kilgallen.

McGee’s recent work on the Deitch Wall on East Houston and Bowery (NYC) is prominently featured on the show’s catalog cover and at the entrance to the exhibition. With longtime collaborator Josh Lazcano (aka “AMAZE”), McGee spray painted simple red tags of the names and crews of graffiti writers from both past and present generations. The legacy of Margaret Kilgallen is featured as the newsstand cover for Juxtapoz magazine’s April 2011 issue dedicated to Art in the Streets. For this particular occasion, the magazine reprinted an interview with Kilgallen from the May/June 1999 issue. This issue is free online thanks to the Levi’s Film Workshop.

Barry McGee and Amaze, "Street Market" installation at MOCA's Geffen Contemporary in Los Angeles, 2011.

Barry McGee, Todd James, and Steve Powers, "Street Market" installation at MOCA's Geffen Contemporary in Los Angeles, 2011.

Barry McGee, along with Todd James and Steve Powers, joined forces to recreate Street Market at Art in the Streets. The installation is their vision of an urban street that includes a liquor store, a bodega, and much more. Battered trucks, bombed with graffiti tags by McGee and Amaze, lay upended on the gallery floor and sprayed directly on the walls. Theirs is one a few of the show’s installations that attempt to bring outdoor work inside. In the Juxtapoz interview, curator Roger Gastman states, “The ultimate celebration of the show is that those artists who are so great in their field are able to capture the feel of the outdoors and the defiant nature in different forms indoors, and intrigue viewers by doing so.”

For many of the artists whose works cover the Geffen Contemporary’s walls and floors, this “untamed expression” is necessary for survival. The endorsement system maintained by the art world and by scholars in academia has not discouraged art outlaws from being creative in public spaces and the clashes between these cultures will continue, even after what I predict will be a successful run for this exhibition. As a basis for my doctoral research, Gothic Futurism (closely related to Afrofuturism), as part of graffiti and street art, integrates history, science, technology, and consciousness. It offers a totalizing look at the impact of the various institutions that govern the behavior and transmission of knowledge. My main motivation for visiting Art in the Streets was to experience the memorial presentation of Battle Station, a rarely seen work by legendary artist and theorist RAMMELLZEE who passed away last year.

RAMMELLZEE, "Battle Station" installation on display at MOCA's Geffen Contemporary in Los Angeles, 2011.

Graffiti and street art pioneers like RAMMELLZEE, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Futura, and others featured in the show have provided artistic guideposts fueled by the increasing ubiquity of computing and information technology that have offered opportunities for outlaw and outsider artists to deviate from canonical forms of art and represent a complex syntheses of biological and technological apparatuses of the body. In Battle Station, “Wild Style” is in full effect, calling forth what I call “urban metaphysics” and cultural production translated into electronic and digital tools such as Evan Roth’s Graffiti Analysis online mobile game project and DAIM’s Tagged in Motion (augmented reality graffiti). This development regards special forms of representation that have been largely unexplored in scholarly discourse and are open for interrogation and debate.

Many of the artists whose works are on display in Art in the Streets have gravitated to the World Wide Web to create archives of their original work and communicate on multiple levels with their audiences in new ways. Fan and followers will appreciate MOCA’s extensive program of artist talks, film screenings, and performances related to the exhibition, but I think the lack of new media and emerging technologies that feature graffiti and street art (including by artists like Futura) is a missed opportunity to connect with and engage visitors who are digital natives. RAMMELLZEE, Futura, and several other street art pioneers straddle modern vs. postmodern, analog, and digital art forms and their work has sparked debates regarding inclusion in the art world/cultural canon for decades. From abstract works created with spray paint to sculpture, performance, physical computing, electronic art, and gaming, the greatest contribution these artists have made was to be original and blur boundaries. The work on display at Art in the Streets has inspired contemporary artists around the world.