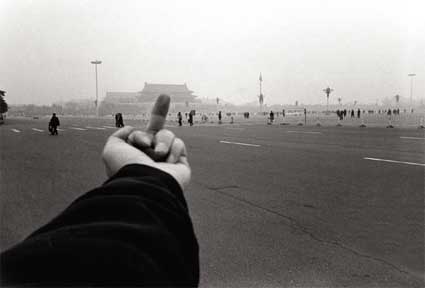

Ai Weiwei, "Study in Perspective: Forbidden City," 1995

When an artist dies, their work changes forever. Whatever it was they were doing at the time of their demise becomes loaded with retroactive meaning and spurious clairvoyance. With the exception of works knowingly produced in the inverted shadow of suicide – Rothko’s hyper-bleak late-60s moonscapes, almost anything on In Utero – most “late works” (in Edward Said’s famous designation) aren’t made with the intention of providing a tragic coda to a life lived publicly, but can’t help but acquire new meaning by virtue of their proximity to death. Painting especially does this: looking at Titian’s astounding Pieta, left unfinished at the time of his death in 1575 and completed by an assistant, it’s almost impossible not to be moved by the thought of the artist’s plague-crabbed fingers dragging pigment across the corpse of Christ. Even Duchamp’s Etant Donnes, designed in secret while the artist had nominally quit art to concentrate on chess, manages to acquire a funereal resonance in its evocation of a tomb (perhaps even The Tomb). David Foster Wallace’s recently published posthumous novel The Pale King will, as I write, be being scoured for allusions to his 2008 suicide, as though his life were lived backwards. In effect, all these efforts are part of the perennial human project to find meaning and pattern in the messy, unmanageable stuff of human existence.

Gustave Courbet, "Still Life with Apples and a Pomegranate," 1871-2, The National Gallery, London.

When an artist is imprisoned, his or her work changes too. When Gustave Courbet was incarcerated in 1871 under a questionable accusation of involvement in violence during the Paris Commune, he produced a small body of paintings necessarily reduced in scale from his better-known works of the 1850s. A small still-life in the National Gallery, made while Courbet was in Sainte-Pelagie prison in Paris, develops an additional layer of meaning in the context of the solitude and melancholy of the prison cell (although the fact he managed to sneak in paints and canvas suggests it wasn’t quite Guantanamo). The minutely detailed phantasmagorias of paranoid schizophrenic Richard Dadd, painted while committed to Broadmoor Hospital in Berkshire, acquire most of their powerful charge from the viewer’s awareness of their provenance. And now Ai Weiwei’s Sunflower Seeds, on display today for the last time at Tate Modern, joins that list. There’s no need to recapitulate the details of Ai’s detention by the Chinese authorities in Beijing (read Michelle Jubin’s excellent analysis here), but it is worth returning to Sunflower Seeds to consider art’s transformative powers, its ability to remake itself.

Ai Weiwei, "Sunflower Seeds"(2011) at Tate Modern. Courtesy Tate Modern.

Sunflower Seeds is a sombre and sober work of art made more so by the unsettling shadows cast over it by Ai’s arrest. The field of ceramic seed pods reads initially as a vast grey carpet, a kind of minimalist anti-monument that both celebrates and bemoans the power and scale of collective labor. Beautiful in detail (each seed is a trompe-l’oeil hand-painted simulacrum of an actual seed) and dizzyingly vast in scale, the work constantly fluctuates between the individual and collective. The orchestration of the making of the work itself is intrinsic to its meaning: made by hand, factory-style, by hundreds of workers, Ai’s piece engages in one of the most conventionally troubling aspects of contemporary art – that it’s usually not actually made by the artist – into something both personally and politically meaningful. The work has already changed once, of course. After clouds of porcelain dust hung in the air during the first few days of its opening, stanchions were erected and the work became a thing to be looked at, not participated in as intended (a similar thing happened at MoMA, when guards were advised not to let children walk on a lead Carl Andre, for fear they’d lick it and keel over).

The enforced distancing of the stanchions created what Duchamp would call “a new thought for that object”: the piece became an image, something to be seen in one go from an elevated footbridge. Yet this transformation failed to entirely defang the work. Suddenly operating on the tension between a withheld sensual engagement and an epic visual experience, Sunflower Seeds became something other, unintentionally generating energy from a Turbine Hall audience’s assumption that they can reach out and touch stuff.

Ai’s arrest has magnified this distancing. The artist’s absence from the manufacture of the work itself, a given in most art made in the last fifty years, has engendered a new sadness with his literal disappearance from the world’s media. And the seeds themselves, which, when held in the hand, felt thrumming with potential energy, have taken on, like Courbet’s pomegranate, the blank muteness of containers, of boxes, cages, cells.