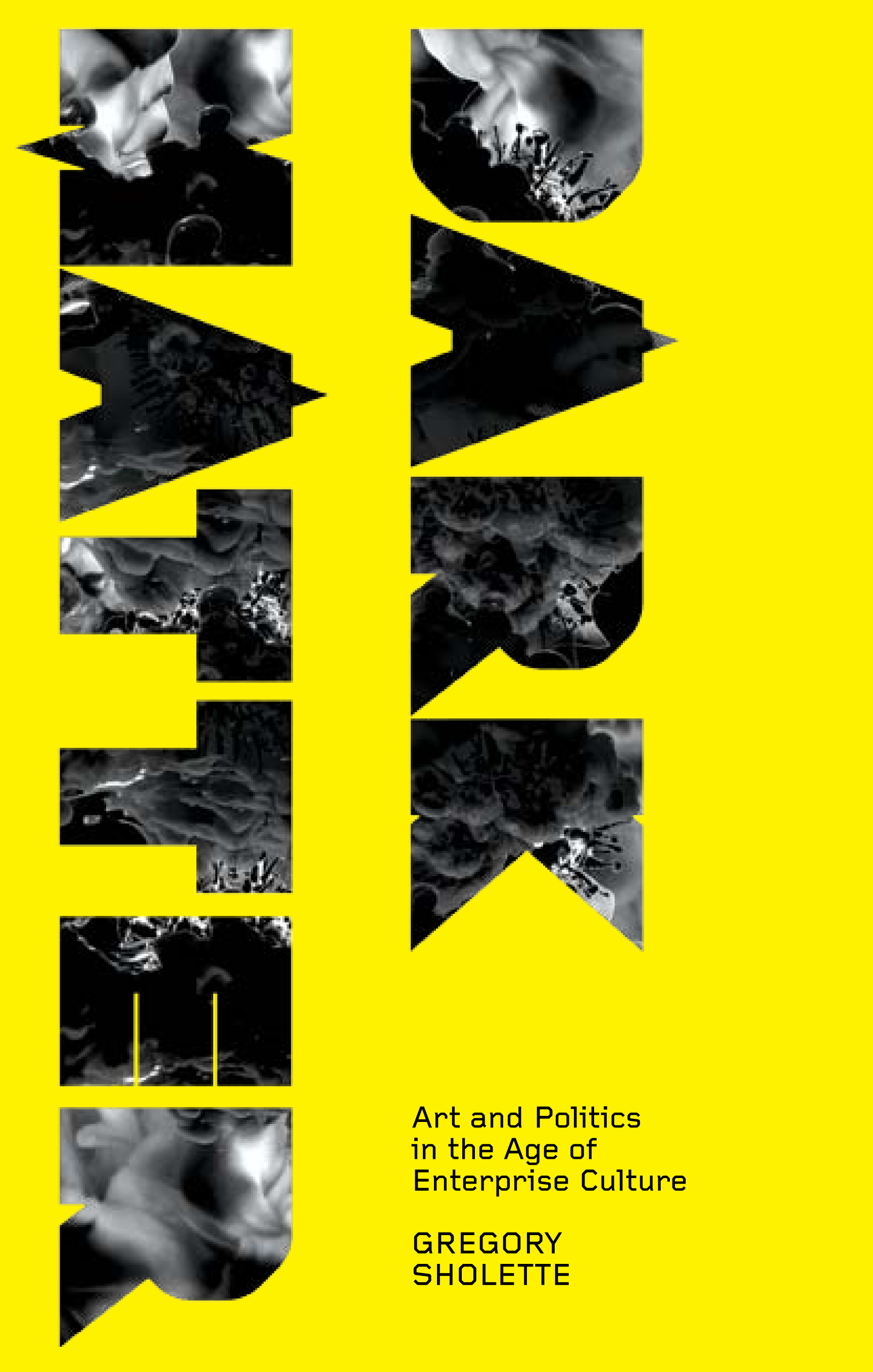

Gregory Sholette, "Dark Matter, Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture," Pluto Press, 2011

Gregory Sholette is a New York-based artist, writer, and founding member of Political Art Documentation/Distribution (PAD/D: 1980-1988), and REPOhistory (1989-2000). A graduate of The Cooper Union (BFA 1979), The University of California, San Diego (MFA 1995), and the Whitney Independent Studies Program in Critical Theory, his recent publications include Dark Matter: Art and Politics in an Age of Enterprise Culture (Pluto Press, 2011); Collectivism After Modernism: The Art of Social Imagination after 1945 (with Blake Stimson for University of Minnesota, 2007); and The Interventionists: A Users Manual for the Creative Disruption of Everyday Life (with Nato Thompson for MassMoCA/MIT Press, 2004, 2006, 2008), as well as a special issue of the journal Third Text, co-edited with theorist Gene Ray on the theme “Whither Tactical Media.”

Sholette recently completed the installation Mole Light: God Is Truth, Light His Shadow for Plato’s Cave, Brooklyn, New York, and the collaborative project, Imaginary Archive, at Enjoy Public Art Gallery in Wellington, New Zealand.

Gregory Sholette and collaborators, "The Imaginary Archive and Wellington Collaboratorium," Enjoy Public Art Gallery, Wellington, New Zealand, 2010

Sholette is Assistant Professor of Sculpture at Queens College, City University of New York (CUNY), a visiting faculty member at Harvard University, and teaches an annual seminar in theory and social practice for the CCC post-graduate research program at Geneva University of Art and Design.

Gregory Sholette, "Mole Light: God Is Truth, Light His Shadow," still, Plato's Cave, Brooklyn, New York, 2010

[audio:https://magazine.art21.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/PLATO-CAVE2.mp3] Gregory Sholette speaks about “God Is Truth and Light His Shadow” at Plato’s Cave, NY, 2010

Being familiar with the angle of Sholette’s work, I picked up Dark Matter and read the Preface and Acknowledgments. Yet before I was done with page 1, I got up to sharpen a pencil. You want to give this book the appropriate attention; it will alert your conscious while enlightening you on the structure of our creative universe. Dark Matter is a metaphor for “amateur, informal, unofficial, autonomous, activist, non-institutional, self-organized practices – all work made and circulated in the shadows of the formal art world, some of which might be said to emulate cultural dark matter by rejecting art world demands of visibility, and much of which has no choice but to be invisible,” in Sholette’s words. The mechanics, tactics, and power of art activism and politicized practices are unveiled with direct references, drawing out the behind-the-scenes of the art world within today’s economic landscape.

It’s an honor to present Gregory Sholette to you today. Sharpen a pencil and pick up Dark Matter.

Georgia Kotretsos: Currently you’re involved with the self-declared artists-in-residence for the US government, the Institute for Wishful Thinking (IWT), which believes that the community of artists and designers possesses untapped creative and conceptual resources that could be applied to solving social problems. Please, tell us about your contribution specifically to this project and your latest work.

Gregory Sholette: In 2008, the noted Hungarian curator Dora Hegyi was seeking work for the 8th Periferic art biennial in Iasi (pronounced “Yash”), Romania, that she was organizing around the theme of “Art as Gift.” Because of my writings on gift economies and informal art, she contacted me. I made her some homemade pizza. I told her about the book I was working on that would focus on the political economy of art, especially that vast amount of invisible labor and imagination that the art world is secretly dependent upon (more on this below). The next day, I contacted the artist Maureen Connor, who is my colleague at Queens College and within no time, Maureen proposed the IWT: an ersatz institute whose primary aim is to provide gifts – useful, secret, or fantastic gifts – directly to those invisible souls who labor behind the screen that separates the public exhibition from its managerial apparatus. Who are these people? Typically, they are young, recently graduated, or out of work artists, art historians, educators, and cultural administrators. And if we think of the screen or curtain as the legendary fourth wall in the theater, except that here it is a white-on-white sheetrock wall, then we are not supposed to notice that behind this partition lurks a shadowy species of creative dark matter. At one meeting, we compared this other realm to the Freudian libido and wondered what kind of fantasies of generosity it would call out for. In Iasi, our attempted emancipation led to unexpected outcomes, but first let me tell you a bit more about IWT.

In many ways, the IWT concept sprang naturally from the mutual interest both Maureen Connor and I share in what might be called the imaginative disruption of everyday life by both artists as well as non-artists. For example, Maureen’s earlier project, Personnel, investigated the “attitudes, needs, and desires” of office staff where she was invited to create an artwork. One manifestation of Personnel transformed the so-called “personal” space of cubicle workers into a boudoir, and another into a campsite. IWT also resonates with my work, in particular the 2002 installation I am NOT my Office, in which workaday fantasies from the practical – I want multitasking centipede limbs or arms like Shiva – to the maniacal – a flying ear that gathers information on office politics – [are rendered] into a series of drawings and “action figures.”

But the real evolution of IWT began when we invited several talented MFA students from Queens College to join us and brainstorm about how to satisfy the fantasies of people we had never met on the far eastern side of Romania. The upshot was to create a website where the Periferic 8 biennial staff could log on and type in the kind of gift they wanted us to fulfill. And there were three categories of potential gifts: 1) a practical gift, 2) a fantastic gift, and 3) a secret gift. Ultimately we brought as many fulfilled desires as we could transport to Iasi including: a modest library of books on art and theory; some photographic materials that were difficult to get in Romania; several felt sleep masks stitched together by agent Kirby as a kind of substitute for a work by Joseph Beuys that the Periferic organizers could not afford to borrow for display; an onsite gift of labor performed by agent Mahler that involved spackling and prepping exhibition walls; a song written and performed by agent Rubin which was gifted to a Periferic staff member who was secretly in love with someone; and finally a stuffed “Kermit.” But for a year, this gift request remained a puzzle to us. On the website someone from Iasi secretly asked for a Kermit. But what did it mean? Was Kermit Romanian slang perhaps? Or was it a reference to a certain green television character as we immediately assumed? Did people in the “Eastern Bloc” actually grow up watching Sesame Street? Since it was a “secret” request, we did not have the option of asking more. Instead, we collectively decided that fulfilling certain gifts gave us license to be imaginative, even a bit subversive. In response to the Kermit request, agent De Felice stitched together a batrachian sock puppet, carried it with her to Iasi for the opening, and after walking around the exhibition for about an hour, a Periferic staffer finally came over, accepted the gift, publicly embracing her desire a secret no longer.

To be fair, we also encountered a degree of skepticism from some of the artists in Romania. And not all of it was unjustified, at least on the surface. I do think in retrospect the idea of bringing “gifts” from the wealthy United States to the struggling economy of a former socialist nation seemed a bit cheeky. This was an insight we needed to have more discussion around, as agent Pavlou thoughtfully suggested at a later meeting. At the same time, few in Romania probably realized just how precarious our living circumstances are sometimes in a place like New York City, especially for recently graduated MFA students, like most of the members of IWT. Anyway, [here is a link] for more on this first IWT project in Iasi.

IWT produced its most recent project, entitled Artists in Residence for the US Government (self-declared) for Momenta Art, a not-for-profit space located in Brooklyn. The mission of this project was to “increase understanding of the art making process and how it can contribute to society as well as encourage policy makers and the general public to think of artists as potential partners in a variety of circumstances.” I suppose you could say that at a moment when actual governmental and social infrastructure has been decimated after thirty years of privatization, deregulation, and economic contraction at the public level, the IWT seeks to make transparent one of the last remaining sources of untapped collective value: the social imagination of those thousands upon thousands of academically trained artists and art students who constitute an invisible army of precarious, over-educated surplus laborers. Like a redundant missing mass, this shadowy creativity is brimming with the possibility of either radical change or precipitous regression. This ambiguity seems especially striking today in the icy grip of the aptly named “jobless recovery.” I will discuss this vibrant dark matter more below, but for now you asked me about my role in this latest project, Georgia, so let me finish here by saying that along with brainstorming ideas with IWT and helping with the physical installation at Momenta, I also introduced our group to THEMM.US, a hitherto unknown collective entity. And although politically unpolished and a bit ribald, their odd little sculptures and experimental thrash songs “for government agencies” were featured on one wall of the exhibition. Funny thing is I am even thinking about collaborating with them on some upcoming project.

The mission of the IWT is ongoing and we encourage new proposals (via our website) that we hope, wishfully as well as concretely, will develop into a new model of support for artists in which they are paid to consult with policymakers and elected officials.

Along with Maureen and myself, The Institute for Wishful Thinking consists of the artists (who are also Queens College graduates): Susan Kirby, Nathania Rubin, Andrea DeFelice, Matt Mahler, John Pavlou, Bibi Calderaro, and Tommy Mintz.

GK: Studying your case, I realized that you do not simply have a studio practice but you rather have an art life which consists of educating young minds, being a practicing artist, a writer, an administrator, an organizer, an initiator, a participator, an activist, and a thinker who looks forward, produces ideas, and generates knowledge. The North Pole is taken, so where do you and your elves operate from?

GS: I am my own “elf.” That is why I often work small, turning out only a few art projects a year. But you want to know what Geppetto’s little red workshop actually consist of? It’s a 5×12 extra room in my Inwood apartment, plus my MacBook Pro loaded with Photoshop. Seriously, I am not opposed to outsourcing the fabrication of artwork when its necessary, but I like making things myself, it’s a powerful anecdote to my research and critical writing, even though one is a direct extension of the other (at least to my mind). I have had assistance with a few projects however, and extensively so with my twin websites including from Andrea De Felice mentioned above, as well as Yue Zhang, William Thompson Harris, and the multi-talented Matthew Greco.

GK: If we were to visualize a pyramid where its tip is occupied by mainstream successful artists, does this mean that what’s right beneath the tip could all be dark matter? Do activists, struggling and failed artists, hobbyists, and amateurs all fall under one homogeneous enormous category or since art activism has continued to earn art historical ground, it’d be best to place it between mainstream artists and everybody else left in the art world?

GS: Thanks Georgia, this is a crucial question and I hope it is acceptable to ask people to read my new book, Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture (Pluto Press, 2011), rather than only download my older essays about dark matter from the Internet. Of course I am plugging my own little capitalist endeavor here, but also significantly, the concept of dark matter or missing mass has evolved over the last ten years. Now when I use the term dark matter, it is meant to invoke two different registers at the same time: one abstract, the other very much concrete. But then thinking in contradictions is something I have learned above all from being an artist.

Dark matter is merely a metaphor, the best I could find, for describing something that has an effect on the mainstream cultural world, but is largely unseen by it. First, think of the art world as an economy with both symbolic and material dimensions. Within this economy, dark matter is both present and absent, detectable at one level, but lacking its own discourse, and therefore all but unnameable. However, (and here comes the contradictory bit), dark matter also describes something concrete, something that has measurable reality, something like the way an offsite archive of key documents adjudicates meaning from afar. So yes, you’re correct: this “missing matter” does includes the various informal activities you mention like amateur and hobby crafts and so forth. But it also incorporates what art historian Carol Duncan once described as the glut of artists who never reach visibility. This, Duncan insisted, was the “natural” condition of the art world. What I hope my research and writing begin to do is to intervene in this so-called natural economy by unsettling and possibly re-politicizing the realm of cultural production itself. Ok, that is grandiose. But what I am trying to get at is that like almost everything else today, art is the outcome of social production. And this fact is diametrically opposed to art’s mythology that revolves around the isolated artistic genius working alone in her studio. Most of us know this is a fallacy. Still, we allow the economy of the art world to divvy up this socially produced wealth like so much “real estate,” as if only a handful of gentry grew above an ever-shrinking commons. Whether this other collective productivity is visible or is hidden, or slides in between both those states of light and darkness, is less the point than to recognize that dark matter production runs through all of these institutions and discourses like a multitude of veins in a piece of marble. That is why the image of the pyramid is less useful or accurate for fully describing art’s political economy (even though admittedly, the towering needle with its broad base or long tail is still a powerful and intuitive representation of the unequal recognition most artists feel as they contemplate the mainstream cultural landscape and their assigned place within it). Therefore even before one begins to speak about “political art,” or “interventionism,” or “relational,” or “dialogical,” or “participatory,” or “philistine” aesthetics (to cite respectively: Lucy R. Lippard, Nato Thompson, Nicolas Bourriard, Grant Kester, Claire Bishop, or John Roberts and Dave Beech), one must first understand there is a political struggle at the level of production. Or as Zizek quipped, “It’s the political economy stupid!”

GK: What are your thoughts on the transition of dark matter from the streets, the web, and the wider periphery to the museum, the podium, and the establishment?

GS: In terms of the apparent recognition of a certain previously unacknowledged informal art, well, it’s just not the case that street art and home crafts have never been part of the art world. I would argue that such practices have always been not only present, but also influential on artists, but simply not named as such. What has happened in recent years is [that] this shadowy archive of heterogeneous messy sentimental everyday imagination is becoming inextricably more visible. For example, look at the incredible art world success of the Young British Artists in the 1990s. One can clearly see the YBAs directly borrowed from this realm of informal, vulgar, and street aesthetics, as if secretly recognizing that [this] invisible mass was on the rise. However, their response was to snip bits of dark matter off, incorporate this into their art, and tack it to the walls of the white cube. Over a decade later, with greater advances in bandwidth and Internet technology, but also an ever-increasing number of people claiming to be artists (see Chapter 5 of Dark Matter: “Glut, Overproduction, Redundancy!”), this other social production is more and more simply representing itself! I suspect we are on the verge of a kind of P2P art world that will run parallel to that of the one familiar to us now. Will this be a significant advance, politically speaking? Will the structural disequilibrium of culture be overturned and redistributed more equitably? In other words, will art world real estate – its assets and symbolic power — be transformed back into something of a commons (though I doubt it ever was that)? These are the critical questions my book seeks in the end to raise with regard to so-called dark matter. And all the while, I am very cautious. Cautious about the mainstream museums and art collectors who are interested in street art, cautious about the way certain corporate interests are salivating over the rise of consumers who produce their own creative content, aka Prosumers, and cautious about the new interest in “social practice” art. Recalling the way “political art” in the United States became a fleeting fashion in the art world of the late 1980s and early 1990s, my antennas of apprehensiveness are twitching madly these days. Let me just cite one quote from Wired magazine that I use at a crucial juncture in my new book:

Previous industrial ages were built on the backs of individuals, too, but in those days, labor was just that: labor. Workers were paid for their time, whether on a factory floor or in a cubicle. Today’s peer-production machine runs in a mostly nonmonetary economy. The currency is reputation, expression, karma, “whuffie,” or simply whim.

— Chris Anderson, editor of magazine Wired, “People Power Blogs, user reviews, photo-sharing—the peer production era has arrived,” Wired, July 2006.

What is invigorating therefore about this explosion of the shadow archive is that it is filled with potentially positive elements and processes like gift economies and P2P productivity. What is not good is that it is already being selectively filtered for incorporation into the values structure of capital. That is one place where a political struggle must be waged. But what is equally or perhaps even more of a concern in the short run is that what I am calling dark matter is also permeated with reactionary, regressive elements. The Tea Party or the Minutemen militias are but two examples. And no doubt there are versions of these anti-democratic tendencies even within our own artistic ranks.

GK: Asking you all the way from Greece, what does economic crisis produce? What have we learned from the past?

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mPgcPFJ-E1M]

Syntagma Square, Athens, Greece, May 25th 2011: Taking the lead from Spain, thousands of people gathered at Syntagma square on Wednesday to protest against austerity measures, responding to a grassroots Facebook campaign. The crowd sings the Greek National Anthem.

GS: For us as artists and cultural workers, it comes down to developing a viable, democratic, counter-narrative that, bit-by-bit, gains descriptive power within the larger public discourse. That said, we first must begin here with us artists, and what we do, and how we create by gaining an understanding of the potential transformative power of this missing creative mass that we are talking about and that we also embody. We need to ask how to use this vibrant inert mass to intervene within the political economy of culture understood as an everyday form of production.

And that’s a wrap!

Beginning with artist, writer, and activist Gregory Sholette, the second round of Inside the Artist’s Studio is commencing. Emphasis will be given to mid-career and established artists in their field who will open their studios and our minds to a world of art that should be protected and supported. The forthcoming posts are addressed to artists of my generation, where I invite them to tune in and listen carefully to their inner art voice. I encourage especially those who primarily concern themselves with production-to-consumption inquiries to follow my column.