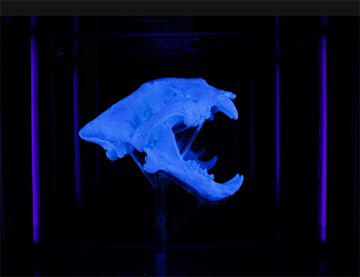

Maya Kramer, “There Is Nothing You Can Measure Anymore,” 2010. Laundry detergent, black light, pump, vitrine. Courtesy the artist.

I first met Maya Kramer at a dinner party she was hosting at her home in one of the tree-lined compounds of the former French Concession in Shanghai. But it was only after we opened the second bottle of wine that I found out she was an artist.

After completing her MFA in sculpture at Hunter College, Maya worked in the curatorial department of the Guggenheim Museum for three years. She first visited China in 2009, to take up a six-month residency at the now-closed True Color Museum in Suzhou, a privately owned contemporary art and performance venue that had been set up by musical entrepreneur Chen Hanxing. Maya was the first foreign artist to be invited to China for the museum residency, and left her mark with a wishing well installation in a grove of paper trees that whispered random desires through hidden speakers.

The idea of establishing a solo practice in China presented a challenging way of both working and living, but two years on from the residency, she is now happily ensconced in the burgeoning art world of Shanghai. Her art practice is concerned with the environment, often consisting of sculptures made from everyday paper waste. She has since extended into collaborative projects, working with notions of value and exchange.

We spoke a few times in Shanghai about the many differences between America and China, the new types of work being explored in the vast number of galleries and museums opening across the country, and especially about the problems of not speaking the language (she does, while I barely scrape by). When I arrived back in New York recently, I interviewed Maya about her work and what she thinks of the now volatile relations in the art world between China and the USA.

Maya Kramer, “There Is Nothing You Can Measure Anymore,” 2010. Laundry detergent, black light, pump, vitrine. Courtesy the artist.

Maya Kramer, “There Is Nothing You Can Measure Anymore,” 2010. Laundry detergent, black light, pump, vitrine. Courtesy the artist.

Din Heagney: I’m intrigued by There Is Nothing You Can Measure Anymore, a vitrine with a tiger skull made from laundry detergent that dissolves over time as water slowly drips on it. The connections you’ve made between endangered animals, pollution, and museum aesthetics make it a very tight piece.

Maya Kramer: Upon completing this work, I was quite excited as it was one of those rare instances where the result matches with one’s original conception. For a while, I’ve been trying to come to grips with a rapidly deteriorating ecology and our place in the world. But in the end, I’ve started to see that everything dies and transforms; it’s inescapable and has nothing to do with us.

I wanted to point to this concern for the environment by fusing various symbols, an x-ray (a diagnostic tool used to examine an underlying problem), a tiger skull (an animal nearly extinct), and laundry detergent (an everyday pollutant), and then have all those concerns literally fall apart.

DH: The materiality in your practice is often selectively paper-based, like the installation There is No Logic to the Days, which used copies of New York Times newspapers. What does paper represent for you?

MK: In both instances where paper is at the project’s core (There is No Logic to the Days and A New History of Diamonds), my interest was in the paper’s form: newspaper and currency.

The newspaper, which was in wide circulation soon after the industrial revolution, reflected that enlightenment logic of progress (still obstinately present in our society). An attitude of: isolate, study, and problem-solve to make things better. But when you read the paper, it’s quite clear the world is not following this ‘progressive’ logic. It’s chaotic, cyclical, and for every new solution there is a new problem.

I wanted to re-work the newspaper, structurally punch holes in it, and scramble its text to reveal the contradictory world underneath the ‘rational’ veneer. Also by turning the newspaper, which was originally plant matter, back into plants, I wanted to challenge the perception of linear progress and reinforce the idea of cyclical time.

Maya Kramer with Anonymous, “A New History of Diamonds 1000,” 2010. Watercolour on paper. Courtesy the artist.

DH: In A New History of Diamonds, you collaborated with a number of anonymous artists to create artist money, a type of creative currency. Can you tell me about this series?

MK: For A New History of Diamonds, I aimed to conceptually re-orient the value of money away from the exchange of goods and services and towards a valuation of ideas, mental and emotional states. Many of my heroes contributed to humanity in an intangible yet incredible way. This project was a means to honor some of these people and to posit what would society look like if we rewarded this drive monetarily. The project also allowed me to survey what people think is beautiful and what I think is beautiful, which is interesting to see.

DH: Some of your other works have also been collaborative in their development and presentation, such as Sugar Spy, a performance commissioned by the Van Abbe Museum for the Shanghai Expo. Do you see this kind of work as separate from your sculpture practice, or a new curatorial direction you’ve moved into? When we were talking in Shanghai, you said you don’t consider yourself a curator or writer and yet you do both.

MK: I absolutely see these projects as an extension of my art practice and not related to my curatorial practice at all. I wanted my work to engage an audience in order to get feedback from viewers that will hopefully prompt further inspiration. I also wanted to see what happens to the work when it directly engages a group.

Honestly, I don’t even feel I have a curatorial practice, as what I do in that regard is quite elementary (it’s more of a job). There are far more sophisticated curatorial endeavors and I’m not trying to compete with them. With writing, I feel I could develop it into something more substantial (right now it’s also still part of a job). If I really get the bug I’ll do it, but if not… I’ve learned not to force things.

Maya Kramer, “From Where It Springs,” 2009. Recycled wood, old bricks, magazines, trash, computer, speakers. Courtesy the artist.

DH: You recently started working with Shanghai Gallery of Art. Do you think there are discernible differences in curatorial or artistic practice that you’ve noticed between the USA and China?

MK: There are similarities and differences in both curatorial and artistic practices between the countries that are really too complex to elucidate here, (and being here for only a few years with an early grasp of the language, I am not a qualified authority). But, to give you a rather broad sense of what I see as the difference: I read a statement by a Chinese artist that China as a country is in itself exceptionally contemporary—which I couldn’t agree with more.

Europe and America are still rooted in Modernism and individualism. Postmodern and contemporary western art discourse has largely been defined in relationship to a western centric Modernist history. Issues around authorship, reproduction/copy vs. original, the relationship between signifier and signified, are roughly 100 years old in the west. Some western art feels pre-occupied with answering these questions. These same concerns aren’t really questions in China. China was closed during a great deal of Modernist development in the west, copying is part of tradition here, and some copies are more valuable than the originals.

Because the language is character based, it is fundamentally pictorial and symbolic, China is at its core more fluent and comfortable with the slippage between signifiers and signified. As world culture moves away from the exchange of text-based information to image-based information, with photographs, television, and the web, I think China’s traditions naturally line up with this way of thinking. Thus artists here can further extend the possibilities inherent in these ideas, more than artists in the west who are still aesthetically and philosophically trying to directly grapple with these concepts.

Maya Kramer, “From Where It Springs,” 2009. Recycled wood, old bricks, magazines, trash, computer, speakers. Installation views. Courtesy the artist.

DH: With the news of Ai Weiwei’s arrest, art media the world over are condemning China as a totalitarian state where artists are suppressed. While I only spent four months there, I have problems with this position, but it is very different from a Chinese perspective. What is your opinion of this situation, because I was at an art party talking to a woman about China, who had never been there, and when I told her about the subtleties in Chinese culture, she said I supported a terrible regime and completely shut me down.

MK: I’m always amazed at how quickly other countries and overseas media etc. feel comfortable making declarations about China while understanding so little about it. I’ve lived here two years, have a Chinese boyfriend, am still a beginner in the language, and I don’t feel comfortable telling you how it is because I still can’t see it from the inside enough to understand it.

I’ve also been at parties in NYC (and expats here call this China-bashing) where I say I can hire someone at a much lesser wage in China than I could in America, do a lot more production, and still give someone a decent salary. Their response: well don’t you feel immoral? It’s as if…a) wages aren’t relative, b) they’ve never bought anything before that was made in China, and c) the economy in America has not been over bailed out many times by China loaning money to the US.

With that said, while Ai Weiwei’s detainment without information and formal charges from the government is undeniably horrible and has the intellectual community in China rightly scared, the situation here is more subtle than outside sources would have you believe. China is far from perfect, there are real abuses of power here, but the West and particularly America very naively assumes it’s so free, that its abuses of power are slight, or that its way of life is best and should be replicated by the rest of the world.

Human rights are important and reforms in this regard need to happen in China, but human rights also need to be balanced with many other considerations. While there are great things about it, I don’t see America as the ideal society. From my perspective, rapid environmental degradation is a more urgent issue than individual rights, (what’s the point of having rights if we don’t have water), and China is doing a much stronger job of addressing those issues than America, which is still the largest polluter per capita in the world. So if America cannot (and is not going to in the near future) address the most urgent needs of our time, why should the rest of the world adopt its way of life?