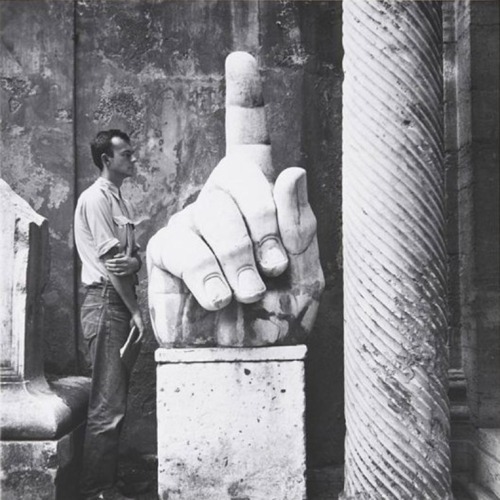

Robert Rauschenberg, "Cy (Twombly) + Relics - Rome #5," 1952

The pairing of Cy Twombly and Nicolas Poussin in the current exhibition at the Dulwich Picture Gallery reveals an embarrassment of shared interests that make it surprising they hadn’t been paired before. Both artists moved to Rome around the age of thirty, making work that reflected back on their native traditions (American abstraction and courtly French Renaissance painting, respectively) as filtered through a reappraisal of the ancient past – which in imperial Rome was a reappraisal of an even more ancient past: that of the Greeks. For everyone concerned, then – from the wide-eyed Twombly of the fifties, having himself photographed by Constantine’s massive digit, to Poussin, wangling his way into the inner circle of antiquarian patrons, to the Romans themselves, gawping back over their shoulder at the silent grandeur of their adopted ancestors – the classical past was something at a remove, to be jolted back to life through art and writing. This cultural electrode-clamping is something so recurrent in Western culture as to be conspicuous only by its absence. And it’s particularly conspicuous now, with the loss of Twombly this week, as though a golden thread, passed from hand to hand, had fallen to the floor.

Nicolas Poussin, "Self-Portrait," 1649 (Gemaldegalerie Berlin)

Classicism’s associations, particularly in the UK, with rarefied educational backgrounds and paternalistic power structures, have always created unwitting cultural and social division. And yet there’s nothing in the work of either Poussin or Twombly that demands any form of classical erudition, despite the exhibition’s abundance of dense wall-labels, which caper about like a neurotic matchmaker, desperately looking for common ground between the two, as they apologize for Twombly’s table manners and Poussin’s inability to crack a smile. The excess of text in the exhibition doesn’t do much to assuage the modern anxiety around the classical past. Classicism is associatively verbal and literary, stuffed away in the mind as interminable verse translation and hypnotic lists of verb endings, and the exhibition, necessarily scaled to Poussin’s advantage, ends up resembling a walk-in illustrated text, rather than a meeting of visual imaginations. And because neither artist requires textual scaffolding, it would be to both of their advantages to knock it away and ditch all wall labels entirely (that’ll never happen, but try walking through not reading anything; there’s only two artists anyway, and you’re unlikely to confuse them). That way, the startling weirdness of the classical mythology that fired both artists up – a child suckled by a goat! Babies born out of gods’ thighs! A cursed swarm of bees! – will come alive, as suddenly and as resonantly as it must have for each of them, and the centuries will concertina, just like that.

Nicolas Poussin, "The Triumph of Pan," 1636 (The National Gallery, London)

In the wake of Twombly’s death this week, his works have acquired, somehow, strangely, a greater ferocity for the spending of the life force that produced them. That skidding mark that whips across the surface of his work might be seen as a continuous thing, carried forward by its own momentum, picking up speed as it moves across the surface of his life, and launching itself, finally, into the future. Hard not to see works like Baccanalia: Fall (1977) as the picking up of a baton passed from Poussin (a print of whose Triumph of Pan is stuck, obscured, to the top of the canvas) to Twombly, whose rushing marks trip over themselves and rush outwards into the next thing, whatever that is.

Cy Twombly, "Bacchanalia: Fall (5 Days in November)," 1977