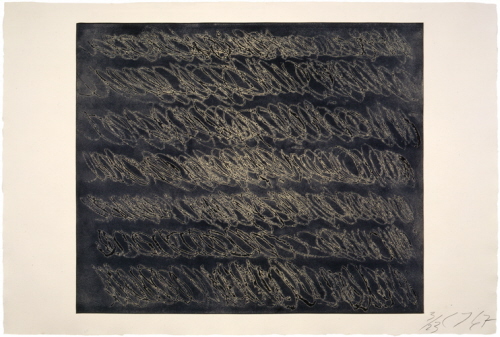

Cy Twombly, “Untitled II,” 1967. Etching, open bite, and aquatint. Sheet: 27 1/2 in. x 40 1/2 in. (69.85 cm x 102.87 cm). Publisher and printer: Universal Limited Art Editions, West Islip, New York, edition 23. © The estate of Cy Twombly/ Universal Limited Art Editions, 1974.

Cy Twombly, who died last month at the age of 83, is frequently described as the outlier genius of contemporary art – a member of the post-expressionist triumvirate of Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg who followed a unique path that confounded the postwar art world. A painter, sculptor, draughtsman, and sometime printmaker, his work renewed classical themes for our times and explored the expressiveness of line in both written and abstracted form. For several decades, Twombly was understood to be an acquired taste. However, his reception has changed over the past several years and he is now firmly placed within the canon. The trend began with a traveling exhibition organized by The Menil Collection, Houston, in 1989. The same year, the Philadelphia Museum of Art acquired and installed a cycle of ten paintings in a dedicated space in its galleries. In 1994, the Museum of Modern Art organized a major retrospective. The following year, The Menil Collection opened a free-standing gallery dedicated to Twombly’s work. In 2001, he was awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale, and a few years later was listed as one of the ten most expensive living artists. In 2008, the Tate Modern organized a major traveling retrospective of his work. Roberta Smith neatly summarized the high regard in which the artist is now held in her eulogy for Twombly in The New York Times earlier this month.

Though printmaking has been an important means of expression for many artists of his generation, it was a brief endeavor for Twombly. The bulk of his printmaking activity was primarily confined to a single decade of his long career – from the late 1960s to the late 1970s – and his output is modest in comparison with Johns and Rauschenberg, who are each prolific printmakers. In fact, a majority of the editions Twombly produced were a result of his close friendship with the latter. That said, he worked in nearly all traditional printmaking techniques during this period, including line etching, mezzotint, aquatint, lithography, and screenprinting. The prints reflect his general concerns at the time they were created, and edition sizes are generally quite small. Many of them were issued as portfolios, in keeping with his mode of painting and drawing in cycles.

Twombly toyed with printmaking early in his career – a rare impression of his 1952 woodcut The Song of the Border-Guard is in the Tate Collection – but did not work in the medium again until the late 1960s. His first professionally editioned prints were created at Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE), West Islip, Long Island, as was the case for a number of artists of his generation. Though Twombly had relocated to Italy in 1957, he continued to spend extended periods working in New York, renting studios downtown on Canal and Bowery. During one such stay in 1967, he accompanied Rauschenberg to ULAE and ended up in the “etching basement,” creating a number of intaglio plates over the following months (see Proof Positive: Forty Years of Contemporary American Printmaking at ULAE, 1957-1997, Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1997, 26).

Cy Twombly, “Sketches: F,” from “Sketches” and portfolio cover, 1967-75. Etching. Sheet: 8 1/2 in. x 12 1/4 in. (21.6 cm x 31.1 cm). Publisher and printer: Universal Limited Art Editions, West Islip, New York, edition 18. © The estate of Cy Twombly/Universal Limited Art Editions, 1974.

The ULAE prints are an extension of Twombly’s investigations into the suggestive qualities of the hand-written line and his interest in unplanned outcomes. He probed the expressive potential of needle-on-metal line etching in Notes and Sketches, allowing his hand to trace over the plate in abstracted loops or notations that recall geometry, bodily forms, and sailing vessels. As noted in Proof Positive, the etchings of the Sketches series were his first prints and he approached them without premeditation, referring to them as “practice plates” (ibid.). Twombly was also attuned to the role of chance in his work – an interest he shared with the composer John Cage, whom he met at Black Mountain College in the early 1950s. In his prints, this approach is apparent in Untitled I and II (illustrated top) – the glowing haloes that surround the abstracted linear loops of these etchings were achieved using open bite, a process that is impossible to fully control. Twombly’s Untitled mezzotint – a technique that is rarely used in contemporary printmaking due to its unforgiving nature – also demonstrates his willingness to allow for the possibility of “error.” In this technique, the artist begins with a textured plate that prints in black and works in the negative to bring out lighter areas; once a mark is placed on the plate it cannot be removed. As a whole, the prints Twombly created at ULAE demonstrate an intense curiosity and intelligent exploration of the possibilities and unique capabilities of a wide range of intaglio techniques.

Following this initial burst of activity at ULAE, Twombly turned to lithography for a few years. These prints reflect the artist’s aesthetic concerns of the late 1960s and early 1970s, during which he created his iconic grey-ground paintings. Volumes have been written on this period, and it is frequently noted that Twombly was deeply influenced by Leonard da Vinci’s Deluge drawings (see examples in the Royal Collection, Windsor Castle) as he developed this breakthrough style. In the late Kirk Varnedoe’s words, this phase of Twombly’s work is characterized by a “nervous, obsessed energy, yet its trance-like monotony also opens out into a sense of serene, oceanic dissolution, in a nebular cloud of great depth and infinite complexity” (Cy Twombly: A Retrospective, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1994, 43).

Cy Twombly, “Roman Notes,” the complete set of six offset lithographs in colors, 1970. Each sheet: 34 1/8 x 27½ in. (86.8 x 70 cm). Printed by Electa Editrice, Venice, published by Neuendorf Verlag, Hamburg, edition 100. Image courtesy Craig F. Starr Gallery, New York. © The estate of Cy Twombly.

Twombly’s first set of lithographs, titled Roman Notes, was conceived as a grid. In this extraordinary suite, six sheets of equal dimensions form an overall composition measuring over six feet square that has the wall presence of one of his canvases. When he created this piece, there were few works of this size in the medium of printmaking, though again Rauschenberg had led the way with his 1967 print Booster (the largest print to have been editioned at the time of its release). Though Roman Notes shares similarities with Twombly’s famous “blackboard” paintings, he used an entirely different palette: the subtle grayish-green backdrop, built up in layers, is complemented by strokes in two hues of Prussian blue.

Twombly achieved a similar effect on a more modest scale in Untitled (1969-71), a subtle grey-and-white screenprint that was originally issued in the portfolio On the Bowery, published by Edition Domberger, Stuttgart. Intended to capture the artistic and cultural renewal of SoHo that was underway at the time, each of the artists included in the publication had a studio on the famed street. Though small in scale, Twombly’s print encapsulates all of the concerns that characterized his work of this period – a moment that became iconic in the artist’s career.

Twombly’s next suite of lithographs were also script-based, but followed a very different line of inquiry – that of variations on a theme. Created in the winter of 1971 at Rauschenberg’s Untitled Press on Captiva Island, Florida, each of the six lithographs is printed with a different combination of ink and paper: brownish-red on cream Arches; grey on olive Canson; purple on white Arches; black on white Arches; brown on tan Canson; and grey on white Arches. The density of line and overall coverage of his signature “loops” is different for each image, and it is clear that Twombly carefully worked out the resonance between the choice of ink and paper for each. The result is a lyrical meditation on the very nature of these two elements within the medium of lithography.

In the mid-1970s, the artist moved away from purely linear abstraction and began to incorporate written references to Classical literature and imagery of vegetation in his work. Twombly’s next major suite of prints, Natural History, Part I: Mushrooms, 1974, was an ambitious project involving several lithography techniques as well as collage and hand-applied color. The ten images in the set are composed of found photographic and printed imagery heightened with bursts of line and hand-written notes in various colors – the overall impression is that of examining the notebook of an ingenious botanist. Twombly followed this set with another titled Natural History, Part II: Some Trees of Italy, 1975-6, which is similar in approach and aesthetic. According to Heiner Bastian, the author of the catalogue raisonné of Twombly’s prints, the artist was wearied by the extensive technical details of printing these two editions (Cy Twombly: das graphische werk, 1953-1984 : a catalogue raisonné of the printed graphic work, New York University Press, New York, 1985, 13). This perhaps accounts for the fact that Twombly’s subsequent work in printmaking becomes considerably less ambitious afterward, eventually tapering off almost entirely.

After producing two text-based suites in homage to the major writers of Classical literature in the late 1970s (Six Latin Writers and Poets, 1976 and Five Greek Poets and a Philosopher, 1978), Twombly’s printmaking activity was sporadic and generally confined to exhibition-based editions or group portfolios, often produced to promote an event or cause. Though the period of his deepest involvement with printmaking was brief, Twombly’s editions represent a microcosm of the artist’s aesthetic inquiries at a critical juncture in his career and demonstrate his keen intelligence and curiosity. Overall, they stand as an important aspect of his work and essential to the legacy of an artist whose work has significantly impacted the course of contemporary art.