"The Cyclorama." Atlanta, Georgia. 2006. Roadside Georgia: https://roadsidegeorgia.com/site/cyclorama.html.

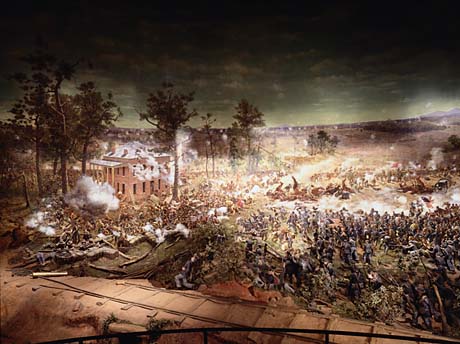

I attended a lecture with Kara Walker on The Art of War at The Atlanta Cyclorama & Civil War Museum. The event was part of a Civil War Summer series, The American Civil War: One-Hundred-Fifty Years Later hosted by The City of Atlanta’s Office of Cultural Affairs and the Atlanta Cyclorama. The Cyclorama is a panoramic depiction of the Civil War Battle of Atlanta, painted on the inside a 42 foot tall cylinder with a circumference of 358 feet. Walker is best known for her room-size panoramic views, which she states, present “an Antebellum swampland wherein mythic and stereotypic characters (as silhouettes), Negro and otherwise, respond to outrageous demands with benign passivity.”

Kara Walker begins her talk with Eastman Johnson’s Old Kentucky Home and the “silhouette” which was popular in the 19th and 18th century and employed by the artist as a narrative device to give graphic recognition to chattel slavery in the United States, and the vestiges of Jim Crow in contemporary society.

“I made a choice when I was in graduate school to stop making paintings and to spend time understanding my subjective relationship to history as painting, understanding my own subjectivity relative to the types of perceptions that were being applied to me from external sources. To recognize how I was viewed in the eyes of others as an African American woman and try to understand what all those types might mean. The reason I found myself doing that was because when I moved to Atlanta at age 13 I found myself subjected to a set of expectations, stereotypes and mythologies that I was not implicated in. [I was] in a way a little like a martian or a nobody. What I wanted to understand as a graduate student was how to assert the agency of a blank space, of an identity that was not informed or reacts against the information that was imposed on it.”

Walker juxtaposes her subjects with the “hyperrealistic” Cyclorama which tells the story of the American Civil War and is a frame of reference with what she refers to as as series of “small-scale interactions that inform history.” Rather than go in the direction of hyperreality, the artist instead chose the silhouette which suited her interest in abstracted, fictional versions of the self. The “blank space” around the silhouette (and the silhouette, itself) became the object that gave Walker the agency she perhaps lacked as a teenage black female. There are occasions when social action takes place around, and may be centered on, objects–silhouettes (dark bodies and faces in panoramas). Social interactions have different meanings depending on the setting–racial dichotomies and conflicts take on different meanings in the artwork, even if much the same things are presented. Objects such as Kara’s silhouettes that are large, complex, and capable of movement (action) are often allowed personalities, and referred to as “she” or the “Negress.”

These objects or representations (panoramas and silhouettes) can be framed by several contexts: from what scholar Michel de Certeau calls “la perruque” (“the wig”) or the devices, actions, and procedures lower class people use to subvert disciplining powers; to what W.E.B. DuBois defines as double consciousness or self-identifying with otherness and society; or poet Paul Laurence Dunbar’s description of the mask that hides one’s true self from its oppressor; or simply as early forms of popular entertainment and art. Like the Cyclorama, Kara’s widely-recognized silhouetted representations, as fictional narratives, are seldom static and we are often lured in (or repulsed) by these works.

A racial dichotomy: African-American dolls made between 1850-1870. Photo courtesy United Federation of Doll Clubs.

Walker presented several antique examples of negative representations of black Americans, i.e. advertisements or images on postcards as jokes that were shared between white men and amplified by the black body or black face.

“Maybe it was because my flawed sense of southerness or my inability to fully grasp the narrative in which I found myself living in Atlanta but I couldn’t imagine the girl pictured as anything but complicit in making the joke. In fact it’s maybe a wish or a fantasy that she be a subject with agency.”

By using various antique images and objects as references, Kara has turned the joke against the original makers with objects that have the power to give people agency. These works can give us different possibilities for creating or re-creating self. This art plays a part in a social interaction. For several years Walker has been exploring pickaninnies, shame, audacity, titillation and the painful legacy of “black Americana,” as well as a backlash (for her work). This was briefly addressed during the Q & A session and I make note of it below. People who think this subject matter is past its time of usefulness need look no further than this summer’s London Olympics, i.e. Gabrielle Douglas’ hair controversy, her choice of uniform, and the “monkey commercial” for NBC’s Animal Practice which was aired “unintentionally” after Douglas’ gold medal performance (NBC has since apologized).

Some of the tweets regarding Gabrielle Douglas' hair after her gold medal London Olympics performance.

“I think that folks get very hung up on racist representations or throwback representations as if I was really making work that is only about slavery and not about the kinds of social terrors that we engage in quite regularly around the world.”

Although Gabrielle Douglas was not a topic of Walker’s lecture, it was hard for me and some outspoken members of the audience not to link these and other recent incidents to the topics and artworks she discussed. Social terror is a contemporary issue and Kara Walker’s past and current works present us with images and narratives that explore these ignoble or “messy acts.”

Kara Walker. National Archives Microfilm PublicationM999 Roll 34: Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands: Six Miles from Springfield on the Franklin Road, 2009.

Kara Walker also talked about her recent work on a video installation and large-scale drawings and prints in an effort to, as she says, “get into a middle space” between existing work and into a “pre-Harlem Renaissance mode.” In this mode she is exploring the identity of the “new Negro” who lives in the space between the rural South and the urban North. For a time she has moved away from making silhouettes and panoramas without totally abandoning them as objects that affect agency.

“It harkens back to this desire to make a piece like the Cyclorama which is kind of a total environment but not to trust the immersion that the Cyclorama suggests, but break it up and let you recalibrate who you are or think you are relative to the thing you’re looking at.”

Kara Walker. "Dust Jackets for the Niggerati—and Supporting Dissertations, Drawings submitted ruefully by Dr. Kara E. Walker," 2011. Courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Kara Walker performing in “Bleed,” by Alicia Hall Moran and Jason Moran, at the Whitney Museum (2012).

Walker says she aims to keep the viewer at bay instead of inviting them in fully. Unlike the panoramas of old, Kara’s work is anti-immersion, an entryway or portal into fictional worlds of her imagination based on historical objects. Her work is not without criticism or commentary. During the Cyclorama lecture she mentions Kara Walker No/ Kara Walker Yes/ Kara Walker?, a book that looks to give a “voice to the previously unheard commentary of Walker’s art world peers raising questions of the unbalanced and unquestioning writings rained on Walker’s work by most of the art critics.” Kara says that she has responded through her work, rather than in letters or presentations. Perhaps it’s easier to see her work in the context of what is happening in our society and in the world. I note this as a black American woman who is hyperaware of my place or position in what Kara refers to as the “arenas of control.” Towards the end of her lecture Walker notes the repetition and endlessness of these events, especially in the United States, which makes her work even more powerful and relevant now.