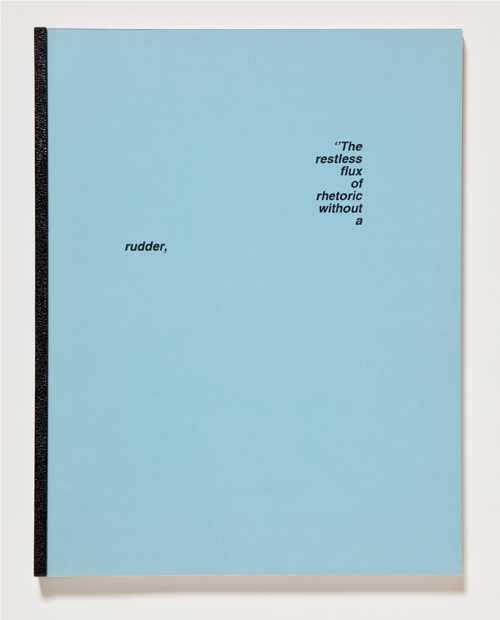

Jack Goldstein. Selected Writings 1994–2000, one of 17 books. Collection Brian Butler, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest, courtesy 1301PE and the Estate of Jack Goldstein.

Jack Goldstein was a seminal member of the Pictures Generation, a group of artists who launched the era of postmodern critique in the visual arts by interrogating the pervasive influence of media representation in contemporary life. Their work is typically characterized by a cool, detached criticality and a rigorous engagement with the au courant mediums of photography, film and video. Much like Richard Prince and Cindy Sherman, his better-known colleagues, Goldstein extracted and reframed elements of representation and spectacle. In doing so however, he utilized a wider range of media than many of his contemporaries—these included film, sound, performance, painting, sculpture, installation, and writing.

When Goldstein had access to money, he typically sank it into production projects. Favoring the removal of the artist’s hand in his work and maintaining a growing interest in the tropes and techniques of Hollywood, Goldstein rented equipment and props and employed assistants to create his short films, sound effects records, and large airbrush paintings. With access to the necessary resources, he was able to generate meticulously manufactured pieces that were utterly lacking in a fixed subjective viewpoint. Works like the 1975 film Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, which consisted of a loop of the MGM lion roaring over and over again ad infinitum, seemed to float in a dislocated commercial hyperspace.

When he didn’t have funds, however, Goldstein would spend what he called “quiet days” working with nothing but text. The earliest example we have of these is the Aphorisms, some of which are captured in a remarkable series of photographs taken by his friend and fellow artist James Welling. The year was 1977 and both Goldstein and Welling had studios in the low-rent Pacific Building in Santa Monica. On the walls of Goldstein’s studio were pinned a fascinating array of artifacts: flyers for the artist’s lectures, media clippings that would later serve as inspiration for film or performance works, Polaroids of works in progress, and numerous Aphorisms, either written by hand or typed out on sheets of white 8½ x 11 paper.

The handwritten ones seemed to be initial drafts, filling the whole of a page and bearing strikeouts here and there. The typewritten ones may have been final presentations, with only one aphorism to a page, neatly centered. In any case, all the sheets of paper were lined up in perfect rows, just like the Polaroids and clippings around them. Goldstein seemed to have everything pinned up like specimen displays, all the better to dissect their signifying impact.

The first aphorisms that Welling documented focused on the half banal, half devastating thoughts of day to day life:

Driving 5 miles to put gas in the car when there’s a gas station around the corner.

I set my alarm for 7:00 Clock but what if it fails to go off.

Lying to yourself even in your dreams

Tomorrow never comes.

My door is on fire.

Goldstein seems to be searching here for the theatricality of everyday existence, attempting to tease it out through words on the page. In the absence of material sources, he attempts to locate psychological fuel for his projects. As the aphorisms evolve during this period, they lose some of their tentative quality and seem to take on more cinematic proportions. In 1978, Welling documented sentences that included the following:

From a distance she looked very beautiful

She dreams of her favorite movie star.

I was so lonely that I had to get on a bus with people

The hero died in slow motion.

The mystery begins with the […] beautiful girl murdered

It seemed as if Goldstein had slowly disappeared his own personal quirks into the deconstructed script of a Hollywood movie. Elements of human pathos and longing are still there, but they are now indistinguishable from the scenes of a film.

Jack Goldstein, Selected Writings 1994–2000, interior view. Photo: Carol Cheh.

Goldstein would take this textual disappearing act, this relentless erasure of the artist’s hand, even farther, perhaps to its logical limits, in his last years. Following his failure to establish a lasting career in New York, Goldstein abruptly retreated back to Los Angeles without telling anyone, holing up in a decrepit East L.A. trailer for most of the 1990s. There, completely bereft of resources, he busied himself with his final work: Selected Writings 1994–2000, an autobiography constructed of scraps of other authors’ writings.

Goldstein would take books by authors such as Kafka, Hegel, and Nietzsche, read them backwards in order to break their narrative, and lift the phrases that leapt out at him. He would then collage three to a page, leaving enormous margins and floating the clumps of text either high or low. A selection of these pages were collated and bound into 17 volumes, with only two copies of the set produced at Kinko’s. The resulting books resembled nothing short of screenplays that one might see being shopped around Hollywood.

Reading these tight, florid little bursts of text, which do have a resonant logic to them, is both frustrating and sublime. Groupings like this one seem to say so much while leading nowhere:

THE IMAGE THAT TURNS THE WORLD INTO MY WORD

“language is the most dangerous possession”

“Since we have been a conversation,

Using literature and philosophy as his material, Goldstein had created one last masterpiece in which he both exerted perfect control and vanished from the viewer’s sight.

Jack Goldstein, Selected Writings 1994–2000, interior view. Photo: Carol Cheh.

Jack Goldstein x 10,000, the first major retrospective of the artist’s work, is on view at Orange County Museum of Art through September 9. It will travel to the Jewish Museum in 2013. The exhibition catalogue, along with Richard Hertz’s 2003 oral history, Jack Goldstein and the Cal Arts Mafia, provided the source material for this essay.