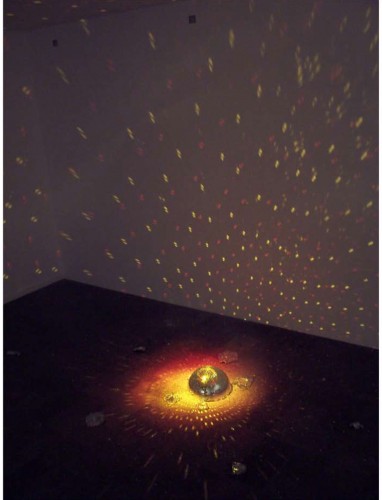

Ha Za Vu Zu. "Let It Be Your Bad Smell." Installation. Westfalischer Kunstverein, Munster, Germany. 2008.

Ha Za Vu Zu is an artist collective, comprised of seven members, which has been working together since 2005. While the group’s practice ranges from installations to videos to all manner of objects—books, flags, banners, mutated disco balls, assorted ephemera—in my view, Ha Za Vu Zu’s particular specialty is performances that play on the thin boundary between performer and audience. Many of their projects, such as “Cut the Flow,” “Crying Performance,” and their performances as a musical ensemble, utilize seemingly simple tools and techniques that almost any audience member could also use, so that viewers can enter and participate in the performance. For example, in “Crying Performance,” the group provides stimulus for tears—onions, lemons, sad, sappy music—and invites audience members to join them in a group cry. In “Cut the Flow,” the group walks down a street arm-in-arm with members of the public, temporarily cutting off the flow of traffic. And when the group performs together as a musical ensemble, they bring their own songs or fragments of songs, but after an hour or so of performing they vacate the stage and turn their instruments over to the audience. For the rest of the performance (which in my experience lasts much longer than the initial ‘set’), the group members move back and forth between audience and stage, chatting with friends and relaxing for a while before returning to the stage to jam with whomever is playing. By instigating the spontaneous formation of new modes of collective action and experience, such performances offer audience members the opportunity to imagine new social orders, new roles for themselves, and alternative modes of political engagement.

I met Ha Za Vu Zu on a hot and humid night a few weeks ago in their studio/practice space, a spacious room in an older building right on Istiklal Caddesi that they have occupied for a year and a half. It is the first studio they have been able to call their own (previously they were residents at Platform Garanti), but soon they will have to leave, as the building has just been sold and will likely be renovated in the manner that all the old buildings on Istiklal have been, making it unaffordable for artists. They are still debating what their next step will be; maybe, they say, they will rent a space to share with some of the other, newer artist collectives that have formed more recently. Or maybe they will just set up their studio in the street. Either way, I am grateful to have had the opportunity to talk with Ha Za Vu Zu on the brink of this change, just as I look forward to seeing where these changes take them.

Elizabeth Wolfson: Let’s start at the beginning. How did you begin working together? Did you all study in art school together?

Ha Za Vu Zu: Some of us studied art, yes. Not all. It’s not important, really.

First point, I remember, was music. We all worked in the same studio, at school, and also we were living together. And then we decided to start making music. Because we didn’t know how to make music. We started to rent a studio, and to play music.

As you said, we are not professional musicians; it means we were in a fine arts school, and we wanted to make something different. Music is like a code, it is very clear for everybody—everybody can sing, everybody can make music. But I think the basic idea is to make something different, this is what we are doing.

Art school was not enough, so we thought, What else can we do? What can we do separately, individually, but we also thought, What else can we do all together? Music was the beginning of the conversation.

EW: So it was both a shared interest in music as a different form of expression, but also something that you could do collectively. It’s actually really brave, I think, to start playing music. It takes a lot of courage to pick up instruments and start playing.

Ha Za Vu Zu: I do not agree with the word “courage.” I would say it’s an obligation. It was an obligation to do something together, or try something together. It’s a personal obligation, also a political obligation. When you say “courage” it’s more romanticized, and we don’t want to do this.

EW: So it was an obligation, then, not a choice.

Ha Za Vu Zu: It chose us, maybe. [laughs]

EW: What comes out of it, that collective work, working together? What is the obligation?

Ha Za Vu Zu: It was to make a sound together, that was the important point. We were not making music like pop music or something. In the beginning we made too much noise, noise noise noise noise. Then we started to make performances, vocalizing performances. Just using our voice.

At the same time, through this vocalizing, we can collaborate with other people. After these performances it always continues. Sometimes we are collaborating with other people, it shouldn’t necessarily be an artist or musician, we can work with everybody. But it’s…

…Not professional….

Because for us the collective working means, at the same time, like this. To speak together.

EW: So it sounds like there’s something about sound. What is it about sound?

Ha Za Vu Zu: To make sound performances was like [making] a fanzine. We collected too much material from the newspaper, television, our writings, we collected all of them together, and we made a video, remixed it, and then [from it] made a karaoke… It was like something, but not directly political, not something romantic… We mixed everything.

Because sound is very basic. Everyone can make sound. Every can make this [knocks on table]. So how can you organize it all together? If you are not a professional musician, how can you talk in the group, how can you work together, what kind of work can you work on? That’s why sound was one of the beginning points.

EW: Sound has it’s own power, somehow. Both a political kind of power, but also its own physics.

Ha Za Vu Zu: It’s more animal, for example. Because if you are speaking, you can speak like a human. But if you make sounds, we are closer to animals.

EW: Working as a collective has its own special dynamic… Working together for that long, seven years, it’s rather rare. How have you managed to continue for this long?

Ha Za Vu Zu: Actually we hate each other. [laughs]

For example, the “Cut the Flow” performance, it’s very quick and very simple. We invite the people to join us, to cut the flow [of traffic] just for a little, just for five minutes.

Ha Za Vu Zu. "Cut the Flow." Performance still. 10e Biennale de Lyon, Lyon, France. 2009. Courtesy Ha Za Vu Zu.

EW: Yes, it’s a very simple example of the power of so many people in a public place.

Ha Za Vu Zu: It’s simple, yes, but also risky. When we do it, sometimes we have some problems.

Last year we did it in the Balkan region, and city by city it changed. And also in Istanbul it’s totally changed. The reaction of the people is always changing. It depends on time, it depends on day….

In Athens, it was the most… During the street demonstrations times, and everyone was out of work, the economic system was collapsing. We just invited the people, and many people came, and we cut the flow of one of the narrow streets. And when people saw, they would just stop and ask, “What is it about?” They just wanted to know what it was about, and they wanted to join or they wanted to be against us. But in Skopje, the situation was really different. There, people were repressed by the police and the state, and the whole city was under construction, and they had a kind of police state there. When we made the performance there, and we made no reaction to the people, they got really angry, and they started to be violent. They were trying to break our arms and saying, “Go to hell, out of my way,” it was really violent. Also in Lyon, when we did it, it was also very violent but in a different way, it had to do with the consciousness of being a European citizen. Because you cannot cut the flow of any European citizen. It’s their right to walk on the streets.

“You are between me and my coffee!” [laughs] “Get out!”

In Istanbul, we can speak of all the reactions together. Here, there were people who were really scared of making a reaction—“If I make any reaction, I don’t know what happens to me.” So some people didn’t react. Some of them didn’t even care, they just passed. And some people were just rudely passing through.

And some of them joined us. “What is this? Oh it’s like a free cinema, ohhhh!!!” [laughter]

EW: It seems to me that there is a bit of a contradiction in Turkish society; on the one hand, family is very strong here, people’s devotion to their family and their obligations are a very strong force in their lives, and families are of course a kind of collective. On the other hand, here as in many other capitalist nations, there has been harsh persecution of labor groups and other kinds of collectives. How does Ha Za Vu Zu’s work as a collective fit into this picture?

Ha Za Vu Zu: It is a good question, because as you say family is very strong here. When you are out of the family you are nothing, you are never an individual outside of the family. You are always part of the family. We have to be connected. In the school we came together, began having conversations, because we wanted to see what else we could do. We already knew the family structure, and also the political kind of togetherness, collective work; what else can we do? To be a cultural group, we don’t want to be a political party or activist group. So that’s why we are working on different working models, to see what kind of relationships we can build. We cannot say we are working like this or working like that; we are still working on our relationship. We can define this as a family also, but a different kind of a family. I don’t accept the definition of family, or I would like to change the content of….

We don’t want to be family. It’s very hard…. We can be family—no! It’s better to be destroying it. It’s very important, I think.

I think first problem we should say, you cannot find a solution forever. We work always on this topic, how to not be a family. “Family” means we know each other. But at the opposite… Of course to make a work is important for us, but relationships are more important.

If you think of the ‘70s there is a collective movement in Turkey, there are different groups, and they are young. There are demonstrations in the streets. But after the military coups… We are just coming from a depoliticized generation. We were just separate, we didn’t have any idea about politics and together, we started working together. We are discussing everything until we convince each other of the idea, the final idea. In this moment I think there are more collectives, but there are different models, because it’s a need, a need to come together again and think about the past, other collectives’ experience, why they are not working together now, and why we are together now. What kinds of groups can we build. These questions are I think important.

EW: In your view, what possible relationship can art have to society?

Ha Za Vu Zu: For example, we can talk about this moment. Two days ago we found out that a bank that is operating in the Black Sea is diverting a river and destroying it. Now we are coming together and talking about our rights. How can we relate this to what is going on with galleries or museums? This is the meeting point with others, not artists, but other people who have problems. And now after two days we are thinking, how can we protest this situation? How can we protest together? How can we make something together? Again the same position, but the topics are changed.

Maybe we can say we are not working for art. We are working for life, and life is bigger than art. Of course we can use some situations, we can use some strategies of art, some ways of speaking, but you cannot separate them and say “I am working for art.”

That’s why maybe nowadays activist groups and artist groups are starting to work together. Or at least they are more in contact. Because the artist group, okay, they have their researches and they are making projects, but they are isolated. But if they are coming together so they can feel each other, this chemistry can lead to something else. Because also activism needs different strategies or more creative strategies. And also art community needs more togetherness or different kind of working orders. And discussing in a wider range.

Ha Za Vu Zu. "What a Loop" performance. Performance stills. 10e Biennale de Lyon, Lyon France. 2009. Courtesy Ha Za Vu Zu.

EW: How do you think of the barrier between yourselves and the audience?

Ha Za Vu Zu: People always look at us and say, “I want to come and join you!” I think this is what we create for people. I think this line is so thin in Ha Za Vu Zu. It looks so simple what we are doing.

EW: But it’s not.

Ha Za Vu Zu: Sure it’s simple!

The power of simple!

We are so lazy!

The power of simple!

EW: But you’re also rehearsing for months!

Ha Za Vu Zu: Yeah! [laughs]

At rehearsals everyone goes, anyone can join. It is the rule. It’s so amazing. We are dancing, we get drunk, that’s it. That’s our aim.

Write it! It’s very important!

If you want to socialize, you have to find a lot of strategies to continue this socializing. Because to be together is not too easy. Mert is right, we hate [each other] at the same together.

Yes, it is true.

The audience cannot last long as an audience. They must enter.

Yes!

Also we cannot act without an audience. We need them.

We should say this: with the audience, against the audience. I like the audience, the audience likes me!