MATERIAL Issue 3. Courtesy of materialpress.org.

Artist-run publications seem to be an especially idealistic enterprise right now. The economy has seriously ransacked the valuing of art along with the funds available to support it, making a costly publishing enterprise foreboding. At the same time, the fast pace and fragmentary nature of the social media world encourages fleeting attention spans and immaterial content platforms. Everything seems to conspire against the assemblage of holdable, perfect-bound volumes of printed words that grapple with and extend the reach of the visual arts.

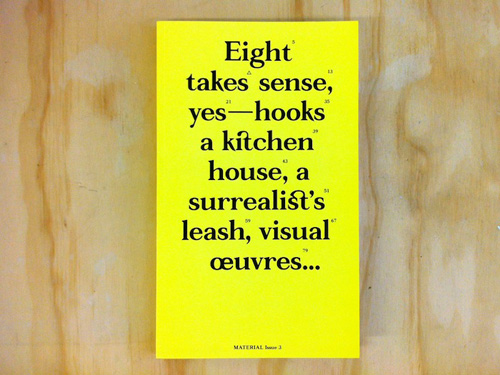

And yet an exciting variety of artists’ publication projects are thriving in Los Angeles. Over the next few columns I’ll be taking a look at selected groupings of these journals, zines, and papers. This month, the focus is on two artist-run journals that recently released new issues: MATERIAL, which was founded in 2007 and just put out issue no. 3, and Prism of Reality, which launched with an inaugural issue last month. Both publications provide compelling textual windows into the city’s rich community of artists and artistic practices.

Artists Ginny Cook and Kim Schoen, who edit MATERIAL, are “interested in the relationship of language to a visual practice—the use of writing to develop ideas, perform critical investigations, and detail observations on art and life.” For each issue of the journal, they assemble a different group of artists and produce a distinct tone; each issue also features a highly unique look, having been made in collaboration with a different graphic designer.

The first utilized a soft, pinkish, vellum-like paper and a folding design that required you to unfold each page, like a centerfold, in order to read the essay that spread out across it. Most of the texts in that issue were fairly direct meditations on artists’ practices, making you feel like you were present while an artist thought out loud about the properties of various materials, or the semantics of certain objects, or the implications of aspects of Baudelaire’s criticism. The second issue, which had a black cover and an exposed spine, contained a more abstract sprawl of literary wanderings, such as an apparent documentation of a walk from the airport to the desert, an adaptation of a lease agreement, and a collection of notes on plants and their associated memories.

The third issue, which had its Los Angeles launch party on October 6, takes “concatenation” as its theme and has an air of jubilation about it that is reminiscent of the early experiments of the Dada era. Behind the bright yellow cover is probably the journal’s most pungent variety of works yet, distinguished by several lively pieces that also function as performance scores. The launch party, which was inspired by a 1923 Tristan Tzara event and dubbed Blow Your Noses! in its honor, nicely leveraged this fact by inviting the authors to perform these and related pieces. Among other performances, Alice Könitz and Stephanie Taylor led a group sing-along to accompany their video, A Leash for Fritz and Kale for Stray Bunny; Harold Abramowitz read from his relentlessly staccato narrative, From a House on a Hill, which both mesmerized and threatened to drive you insane; and Emily Mast let the audience randomly dictate her readings of numbered aphorisms by Édouard Levé, which she had translated from French herself.

Cover image for Prism of Reality Issue 1. Photo by Ian James.

The broad range of works supported by MATERIAL often feels utopically carefree in its expanse. A certain utopic urge also informs Prism of Reality, the new endeavor edited by artist and Artforum contributor Travis Diehl—albeit in an entirely different and perhaps less carefree manner. The journal takes as its unlikely inspiration a passage from Ronald Reagan’s autobiography: “…We now viewed them through a prism of reality.” In his opening statement, signed by hand in every copy, Diehl talks about how the simplistic and duplicitous rhetoric of the neoconservative movement has become so deeply ingrained in our consciousness it now dominates the direction of our culture. One complete reality can only be fought with another complete reality, and this is what the journal sets out to do—to give artists, who in this era are all too prone to “shiftiness” in their discourse–a space in which to practice and congeal their own reality. As Diehl writes, “We aim to raise the stakes of art and art discourse… In these pages, we treat art not as an image of the world as it is or should be, but as the world itself—a self-evident visuality, de facto and absolute—the world through a prism of reality.”

It’s a compelling mission, and the first issue goes a long way toward setting up that prism. The bulk of it is taken up by two in-depth artist conversations and two feature essays by artists pertaining to their practices. The conversations are notable for avoiding the unbalanced interviewer/interviewee format in favor of group dialogues in which viewpoints are equally generated by all parties. “Discotopias” is an inspired pairing between Meghann McCrory, whose works have dealt with California boosterism and the 2010 Shanghai Expo, and Michael Parker, who is known for his Steam Egg, a disco ball sculpture that functions as a sauna room. Fascinatingly, the two share a preoccupation with both utopian thought and the symbolism of disco balls, and their conversation is an absorbing consideration of such.

Also included are four short reviews written by artists. These are more imaginative and exploratory and less didactic than mainstream reviews typically tend to be, and thus strike a nice balance between journalistic responsibility and literary pleasure. In addition, the journal is spiced up by the inclusion of postcards inserted between the essays that act as illustrations of the works discussed. I would guess that this was partly a cost-saving measure, eliminating the expense of printing color images, but it also serves to enliven the reading experience and expand its tactility. Overall, the consistent strength and high quality of the writing in Prism of Reality leaves a solid and lasting impression—a most welcome antidote in this age of careless and short-sighted cultural rhetoric.