I feel the impulse from time to time. A momentary desire to run a finger across the surface of a painting. It’s easily suppressed, however, and passes without another thought. Certain artworks reliably trigger the urge every time, while most do not. If you could touch one artwork, in any museum, which would it be? And what would you be seeking?

Children explore the world through touching, ceaselessly compiling a tactile catalogue of the visible world. In time, a child amasses a rich library of sensory pairings, the retinal impression reinforced with a comprehension of the physical. Gradually, after years of sensory stockpiling, the compulsion to handle everything subsides.

But in fact the need to touch things never truly goes away—it is easily reawakened in the presence of new and strange things. New designer products routinely seduce us with novel finishes, engineered to inflame our appetite for fresh tactile sensations. The impulse can also awaken at the promise of a known reward: we are moved to stroke velvet not to gain new knowledge, but because we know it will gratify.

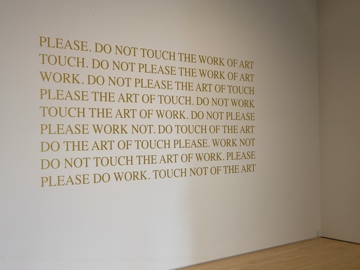

Museums discourage all manner of touching. Although there are children’s museums, petting zoos and others that offer tactile experiences, those constitute a small minority. The prohibition against touching is so deeply entrenched in museum culture that it is seldom even stated: signs advise us when not to photograph, but only rarely tell us not to touch. Codes of behavior in museums are communicated to us subliminally, telepathically via architecture. But even while the rules aren’t articulated, most patrons readily abide by them.

And yet, museums are precisely the sorts of places where we might hope to encounter something strange and new, igniting our desire for sensory experiences. As touch-averse environments, museums restrict our experience mainly to the visual-cerebral. It’s fairly typical to see adults drift through museum galleries with their hands clasped behind their backs. I do this, too—possibly to suppress my own anarchic urges, or to communicate my subservience to the regime: I understand the rules; I pose no threat.

Even while most visitors follow protocol much of the time, exceptions occur, and whether out of curiosity, rebellion or obliviousness, visitors sometimes fail to keep their hands off the art. Any museum guard, conservator or docent can tell you these incidents are not infrequent. I began asking friends and colleagues which artwork, if they could choose one, would they touch? In my informal survey no one hesitated; everyone had an answer either instantly or after a few moments of reflection—all were acquainted with the urge.

I also asked what they would hope to gain, or to experience, from touching. I imagined that to answer this, one must articulate a deeper, subtler aspect of relating to the art. But most often, I found that even those who could readily name the object of their choice couldn’t explain the underlying reason. I anticipated stories, and instead found that people often had no words to describe the impulse.

One friend named Brancusi’s Mademoiselle Pogany, after giving it some thought. As he described the sculpture, his whole body became engaged; he moved his arm in a slow arc, torquing and lilting to illustrate the spiraling movement of the piece, embodying its contours while he spoke. Clearly his experience of the work is a physical, bodily one. To touch its marble surface, it would seem, could only serve to complement its somatic spell.

Which works in a museum get touched the most? I asked a conservator at SFMOMA, who outlined a few broad trends: “People generally touch things that are between waist and shoulder height,” she offered; “if they have to bend down, they won’t do it.” She described prevailing tendencies—industrial materials are touched more than traditional art materials; a Gehry chair in a design exhibition gets more direct contact than a Matisse bronze, for example. She added, “Tactile or cool objects are touched more than artwork that is challenging. Thomas Schutte‘s polished aluminum figures, for instance, are touched more than Damien Hirst’s medicine cabinet.”

The conservator’s characterizations hint at something banal: that objects with fetishy finishes trick the visitor into thinking they’re not in a museum but in a high-end retail store. After all, these are the same materials we are accustomed to pawing in showrooms where handling is allowed or even encouraged. It’s possible to think that contact isn’t always born from unspeakable desires or childlike wonder, but rather in a semi-somnambulistic trance.

Moving parts, particularly controls such as levers and buttons, expressly beg to be touched. Who, upon seeing Calder’s Goldfish Bowl (1929) hasn’t craved to turn its delicate wire crank? An assemblage by Jasper Johns called Souvenir hangs at SFMOMA, consisting of three objects attached to a canvas: an inert flashlight, positioned beneath an adjustable bicycle mirror, whose surface angles toward a ceramic plate bearing an image of the artist’s face. A wall label offers a tour through the artist’s use of these symbols and concludes: “If turned on, the light from the flashlight would presumably reflect in the mirror, illuminating the artist’s image. Instead, these nonfunctional objects, off-limits to the viewer, only frustrate and confound.”

Jasper Johns. “Souvenir,” 1964. Encaustic on canvas with objects. 28 3/4 x 21 in. (73 x 53.3 cm). Collection of the artist, extended loan to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; © Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

This unusually candid curatorial commentary hints at a disconnection some visitors feel when in front of this work. I spoke with an associate curator of education, who has frequently witnessed the frustration visitors have with Souvenir. They want to know: does the flashlight work? Would the mirror really reflect the beam of light onto the plate? Was the work ever displayed with the light on? And so forth. If only they could try the switch on the flashlight, they might find themselves a step closer to “getting” the work. Instead the work implicitly promises interaction while the museum simultaneously withholds it.

In my informal survey of colleagues and friends (most of whom work in museums), I noticed a very distinct theme emerge: that of feeling a deep connection, not only with the object, but with the person who made it. One colleague described wanting to place her hands on a Giacometti bronze to follow the impressions left by the artist’s fingers. Another recalled holding a paleolithic hand axe at the British Museum, among the archaeological objects sometimes made available for handling. In a vitrine it would have remained a nondescript lump of rock, he explained. But with the tool in his hand, he found a proper grip, and with it came a profound feeling of empathy. Holding it in the manner its owner would have held it sparked a sense of connection to someone who lived hundreds of thousands of years ago.

But just as often, the people I asked couldn’t find words for what they believed they could gain from touching. The one person I spoke with who readily confessed to illicitly petting a work in a museum said only: “I found out what I needed to find out.”

Tim Svenonius is Producer of Interpretive Media at SFMOMA and maintains an art practice in San Francisco. His writings can be found at www.sacredbeast.net.