Part one of this interview is available here.

Georgia Kotretsos: I find comfort in your work because you insist on studying, researching, and experimenting with the practice of the artist, and in an effort to primarily demonstrate how artists know things and then produce concrete or speculative knowledge on the very subject. Your own practice has evolved to a degree where the conference, the symposium, the summit, the workshop has become what the gallery space is for the average artist. What choices have you made that got you here today?

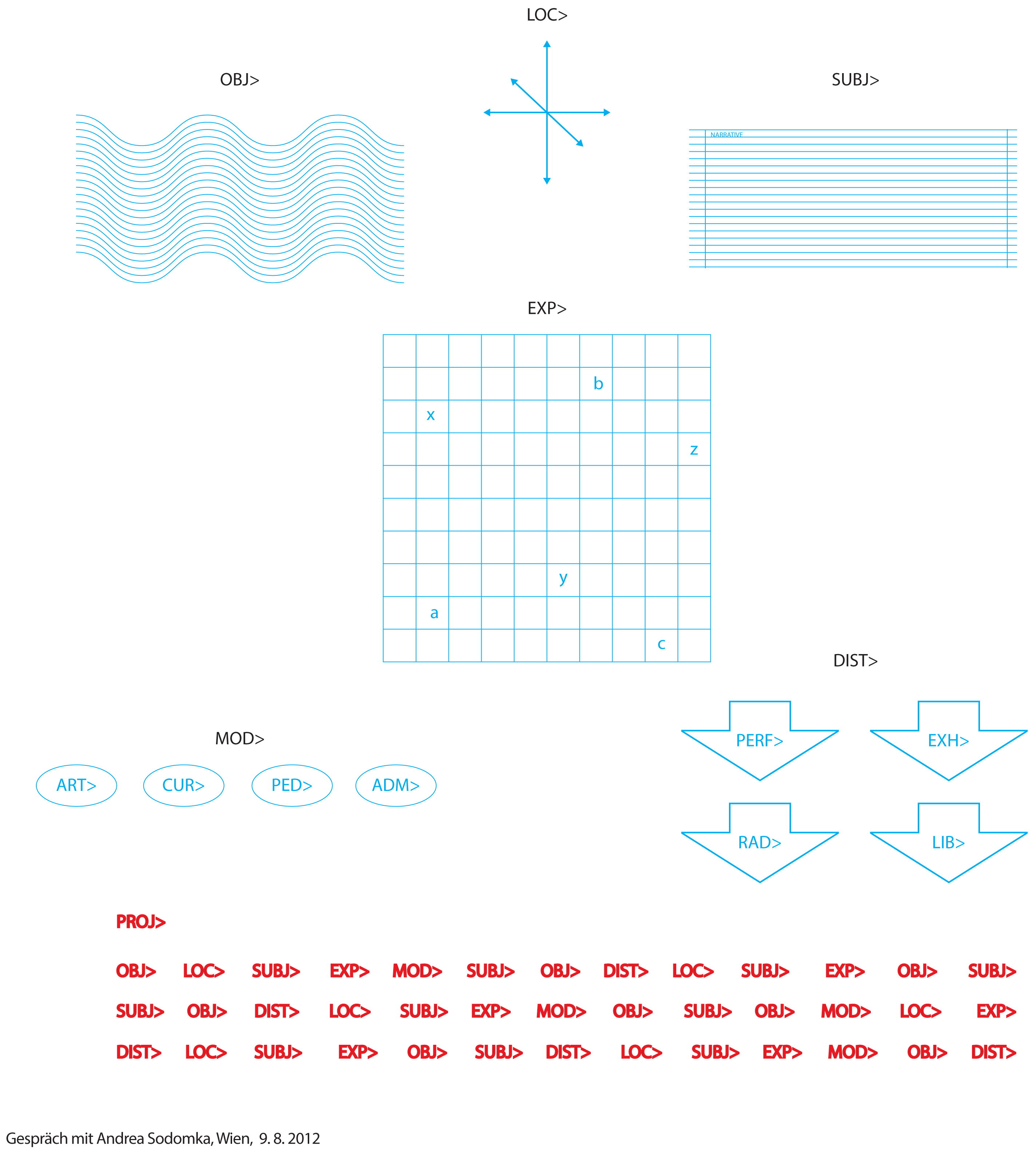

Adelheid Mers: My main pleasures are reading and grasping the design of what I’ve read, which I find through drawing. I grew up with a subscription to Scientific American with its plethora of diagrams, as well as with contemporary art, music and its visual notation. An early and big moment in my life was when my biology teacher asked us to draw a bacteriophage from description. I was the one who could do it at the board. At 17, I diagrammed Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus from sheer desperation. Not sure it helped, but the impulse was there. At 19 years old, my first “serious” piece in art school was a sculpture based on Benjamin Lee Whorf’s Language, Thought, Reality. Over the next years, I struggled with figure/ground relationships through many media, trying to arrive at a singular mode that eliminated that dichotomy. When I started to teach, diagrams ordered content again. Only in 2000 did I realize explicitly that diagrammatic thinking was at the core of all my efforts, solving the figure/ground dilemma for good. Many figures constitute a ground. I have focused on diagramming since. At the same time, diagram research exploded, much of it centered in Germany, Austria, and Scandinavia. Here is a key statement, expounding how diagrammatic practice is bound to discursive platforms:

“The specific strength of genuine diagrams is grounded in what can be designated as their pragmatic potency. More than other forms of discourse, diagrams are designed to engender activities. These activities encompass the entire realm of social action, exceeding the discourse that verbally explicates it. The diagram appears as an area that trades in meaning, a semiotic stop between producer and recipient. In relation to a specific topic, the producer of the diagram aspires to a synthesis of components which themselves constitute the world scenario that is deemed relevant. Formally, this synthesis is marked by a certain symmetry and boundedness. The recipient encounters this apparently ideal object as one who shall unpack its structures of meaning that are seemingly at rest, to unfold them into discourses and practical activities. The scientific research of diagrams will have the task to reconstruct these opposing movements of production and reception, which are not simply to be described as symmetrical.”

My translation of Steffen Bogen/Felix Thürlemann, “Jenseits der Opposition von Text und Bild” in Alexander Patschovsky (Hrsg.), Die Bildwelt der Diagramme Joachims von Fiore: zur Medialität religiös-politischer Programme im Mittelalter, Stuttgart, 2003, S. 1-22.

GK: Are we as artists trained to listen? How important is it for our work, really? Also, you give immense emphasis to creating dialogistic conditions, where equal parts of give and take are required from all parties. What are the benefits of a good conversation for the arts?

AM: Hearing and dialog are important on two levels, the fundamental one is addressed by Vilém Flusser in his essay “Celebrating,” which I’ll briefly summarize here: Judaic tradition revolves around time out of time, the Sabbath. Platonic tradition has carved a space out of space, the Academy. The Sabbath is connected to auditory concepts, it represents a calling. The Academy is a visual device; it leads to theory (theoros = the spectator). Together, they have shaped the contemporary Western, secular Judeo-Christian leisure and knowledge economies, culminating in the Telematic society. The Telematic society is expected to evolve into a dialogic condition in which “own programs” that are proprietary have been abandoned in favor of “other programs” that are shared, similar to open source. Once the ratio of work and leisure tips, through increasing automation, humanity will spend its time “in purposeless play with others for others,” having reached a state of celebratory existence.

While the last bit isn’t about to happen, celebratory existence, and with it the dialogic, is something the arts contain in their nucleus. And as I am exploring, in the context of critique, that same celebratory mode can be evoked in a well-conducted studio conversation, propelling participants’ practices.

“The Studio,” published April 2010. Inkjet on mesh. Mers: “Commissioned for exhibition, my diagram sketches out the history of the artist studio in context. It is based on materials about the show that curators Michelle Grabner and Annika Marie provided me with during the planning phase, including an advance copy of the book ‘The Studio Reader: On the Space of Artists,’ a co-publication of the University of Chicago Press and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, edited by Mary Jane Jacob and Michelle Grabner, with special contributions by over 20 artists…”

GK: Do you see yourself paying more attention to sound?

AM: Sound vexes me. I find it’s presence overpowering. I love to dance but am afraid to sing, so much so that I have started to take singing lessons. I have a sizable collection of Brazilian music. I wish there were more organ concerts in Chicago. I love dirty, open, reverberating sounds. I want to know the sounds of shapes, and I am poking around on the Internet to learn about echolocation. In short, yes, I am paying a lot of attention.

GK: What else would you say to me if I were right there?

AM: In many conversations, power is negotiated by attempting to own, assume, imply, obstruct, or otherwise set premises. Diagrams make premises visible. Because of that, they can be perceived as limiting, demanding, and authoritative structures. They can also be seen as instruments that can be played, activated, and modified. In themselves, they are neither. How they are used depends on the mode the reader is in and on the form of presentation. Those poles have to be negotiated. This is a political question, and it necessarily frames “other programs.”

And that’s a wrap!