Martin Puryear painting Asphaltum on a copper printing plate at Paulson Bott Press in Berkeley, CA.

Production still from the series Exclusive. © Art21, Inc. 2013. Cinematography by Bob Elfstrom.

“Prints are direct. It’s very freeing to work so directly. There is an element of immediacy about it, or there should be. In my hands it often isn’t because I tend to be difficult to satisfy in terms of getting it the way I want it.”

In today’s Exclusive episode, Martin Puryear discusses his interest in printmaking and how the directness of the process contrasts with the accretive approach he takes to sculpture. Shown in 2002 at the Paulson Bott Press in Berkeley, California, Puryear employs skills he originally learned while enrolled at the Swedish Royal Academy of Art in Stockholm.

In watching the artist etch and paint copper plates, I am struck by the ease and focus he seems to have despite the bustle about him; his undivided attention is given to each mark and brush stroke. Though I cannot attest to his thoughts in these moments, the repetitive actions are for me almost hypnotic to observe. When the print is handed off to the printers to be pressed, Puryear’s demeanor seems to shift. One can sense a level of anxiety, however slight, once he has placed his work in the hands of others, and when the final image is about to be revealed.

In an unpublished interview conducted by Art21 in 2002, Puryear speaks about his preference for handling materials with his own hands, which can be traced to his time stationed in West Africa as a member of the Peace Corps.

Detail of Martin Puryear painting Asphaltum on a copper printing plate at Paulson Bott Press in Berkeley, CA.

Production still from the series Exclusive. © Art21, Inc. 2013. Cinematography by Bob Elfstrom.

Puryear was inspired by the high value placed on handmade objects in West Africa and describes how this later influenced his approach to art making:

“I think the influence that I felt most strongly was actually observing people who worked with hand tools, who could build things with hand tools. Because in many cases they didn’t have electricity so it all had to be done by the power of the muscles in the arms and the back. And the school that I taught in was completely built and furnished by people who had no electricity. All the benches, school desks, library bookshelves, doors—everything was made by a carpenter in town. Seeing that kind of joinery in the sixties being made with hand tools and hand-powered, it gave me a sense of independence from what I felt was such a crucial thing back home, which was the electric socket, and expensive electric tools, to be able to do things…That was liberating, particularly in the early years when I was starting out, to know that I could rely on some hand tools and a work bench to produce some work that I really could get involved in.”

Though Puryear now enjoys the privilege of working with master printers like the team at Paulson Bott Press, he still believes that “if you’ve got the right tools, you can do it all using your own physical body.” As electric tools become only more plentiful and seemingly necessary to young artists, Puryear inadvertently offers words of advice:

“A lot of people starting out get hampered because they can’t afford to set themselves up the way they think they need to. I think being in Africa showed me that you can start with a real modicum of physical support if the will is there and the know-how to do it.”

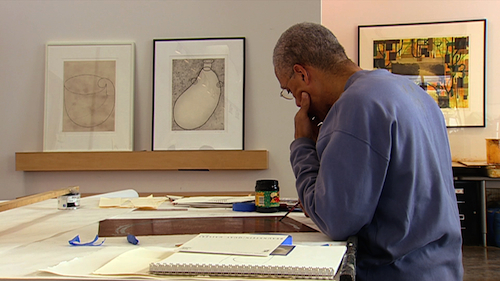

Martin Puryear reviewing a finished print at Paulson Bott Press in Berkeley, CA.

Production still from the series Exclusive. © Art21, Inc. 2013. Cinematography by Bob Elfstrom.

Featured in today’s Exclusive (below) are some of Puryear’s sculptures shown at McKee Gallery in New York. In many of these works, he explores the same ideas reflected in his prints.