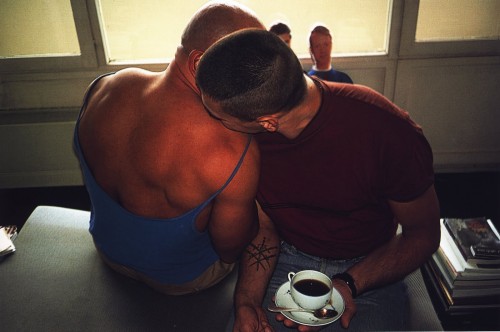

Nan Goldin. “Gilles and Gotscha, Paris,” 1992-93. Cibachrome print. Courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery, New York/Los Angeles.

There are many ways to remember any given year: defining political or global events, sports championships or perhaps even where you were dating or where you were living at the time. The New Museum’s current exhibition NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star looks back to the art scene twenty years ago, presenting a time capsule of sorts of works made (or exhibited) in New York in 1993. The exhibition’s somewhat unwieldy title is taken from the album of the New York rock band Sonic Youth, which was recorded in 1993.

Personally, I usually look back at the recent past through the lens of film. It certainly doesn’t feel like twenty years have passed since Unforgiven, Clint Eastwood’s still-timely deconstruction of the genre of the Western, won Best Picture at the Oscars. Then again, looking at other Oscar winners from that year makes it seem quite distant: Marissa Tomei won for her supporting role in My Cousin Vinny, and in 1993 “Whoo-ah, Whoo-ah” was ushered into the popular cultural lexicon with Al Pacino’s winning lead performance in Scent of a Woman, unbelievably still his only Oscar win. Conjuring a very particular moment from the historical past can produce either a telescoping or a distancing effect, and while the New Museum’s time capsule exhibition includes some art that seem decidedly dated twenty years on, other works seem as relevant now in 2013 as they did in 1993.

NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star opens strong with a video by Alex Bag, who was student at Cooper Union in New York at the time. In her video Untitled (Spring 94) Bag performs for the camera in a work that seemingly anticipates more recent trends, including YouTube confessionals and Ryan Trecartin videos. Donning different wigs and wittily invoking a broad range of pop culture references, Bag takes aim at the banal forms of mass media, simultaneously revealing and mocking the thick layers of clichéd artifice that define the private universe of this girl performing before the video camera, and by extension the collective psyche of the MTV Generation. In the course of Bag’s thirty-minute video, the girl earnestly sings Salt-n-Pepa’s “Shoop,” talks about movies and rock stars with typical teenage delirium, and animatedly discusses everything from McDonald’s to Columbia House’s mail order CD club (remember that?) and other signs of mass commercialism. As she channels a pastiche of identity-defining fads, Bag offers a witty and captivating parody of angst-filled teenage hysteria, self-absorption, and shortening attention spans in a manner that uncannily anticipates the Internet age to come.

Nan Goldin. “Gilles and Gotscha, Paris,” 1992-93. Cibachrome print. Courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery, New York/Los Angeles.

If Bag’s video seems more current than some of the other works on view, others remain particularly significant for their expression of the themes and concerns of their age. Gilles and Gotscha, Paris (1992-1993), a suit of four photographs by Nan Goldin, is perhaps the most powerful of several works on view that gesture to the AIDS epidemic that had by 1993 taken so many lives both within the art community and beyond it. Goldin rose to prominence in the 1980s producing images of friends and family in a diaristic photographic style that had the immediacy and authenticity of a snapshot aesthetic. In Gilles and Gotscha, Paris, Goldin captures intimate and unguarded moments between her art dealer Gilles Dusein and his partner Gotscha as Dusein was dying of AIDS-related complications. Perhaps the most poignant photograph is of Dusein’s arm, withered and ravaged by the AIDS virus, set against the stark white sheet of his hospital bed. While the power of Goldin’s photographs resides in the way she universalizes themes of love and loss, these works also function as palpable reminders of the ways in which homosexuality and the ongoing AIDS crisis were in 1993 deeply polarizing and contested issues in social and political spheres. When viewed from the present moment, Goldin’s images stand as introspective testaments to how far we’ve come both socially and medically but also how much more still needs to be done.

David Hammons. “In the Hood,” 1993. Athletic sweatshirt hood with wire. Courtesy the New Museum and Connie and Jack Tilton, New York.

One work that resonates particularly strongly from the vantage point of 2013 is David Hammons’s In the Hood, in which the hood of an athletic sweatshirt hangs isolated on a wall. Evoking everything from hip-hop culture and vernacular speech to police profiling and the KKK, in the aftermath of Trayvon Martin’s death in Florida in 2012, Hammons’s hood seems almost prophetic, taking on another layer of significance that makes it as timely and relevant today as it was in 1993.

So too does Gillian Wearing’s photograph I’m Desperate, taken during the depths of a global recession in the early 1990s. Asking passersby in the Regent’s Park section of London to write down their thoughts on a sheet of paper and then photographing them with it, Wearing produced a set of searing images that are as much an emblem of 2013 in the wake of the so-called Great Recession as they are of 1993.

Perhaps the finest work in the exhibition is Nari Ward’s installation Amazing Grace, in which over three hundred abandoned baby strollers collected by the artist from the streets of Harlem are displayed amid hundreds of feet of flattened fire hoses. Originally installed in an abandoned fire station in Harlem in 1993, Ward’s installation is both melancholy and hopeful, a field of artifacts that vibrate with untold stories and possibilities, as a recording of the song “Amazing Grace” by the gospel singer Mahalia Jackson fills the cavernous space. While at first the installation seems imbued with a profound sense of loss, the sound of Mahalia Jackson’s warm singing voice pushes back at such an initial reading of the work, instead transposing the installation into something much more hopeful, affective, and alive. Here, partial and fragmentary meaning becomes not, or not simply, the work’s defining condition, but also sign of possibility in a work as much about future change as about past longing.

Nari Ward. “Amazing Grace,” 1993. Baby strollers, fire hoses, sound. Courtesy the artist.

Ward’s Amazing Grace is a standout in this time-capsule exhibition that on the whole avoids any explicit or provocative re-adjudication of the long and deep veins of political and social concerns that so clearly ran through the art world in 1993. It is perhaps the inherent problem of any exhibition such as this that is intent on taking a snapshot of a moment in time: such an archival impulse, with its focus on excavating the past, tends to feel particularly dated if it isn’t also conscious that such an impulse is as much about how society view’s itself now as it viewed itself then. And while the show at times strains under its self-designated ambitions to excavate a particular moment in time, works like Amazing Grace help NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star largely avoid such a self-inflicted wound. Indeed, Ward’s, Bag’s, and a handful of other works continue to seem as powerful and provocative today as they were twenty years ago.

NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star is on view at the New Museum in New York City through May 26, 2013.