“In societies where modern conditions of production prevail, all of life presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation.” —Guy Debord (1931-1994)

In the spring of 2011, the UK-based interventionist art duo known as Benrik launched Situationist, an iPhone app influenced by the mid-century avant-garde movement of the same name. Designed to “make your everyday life more thrilling and unpredictable,” the app used geolocation technology to alert members to each other’s proximity and encourage them to interact in random situations. Curiosity got the best of me; I could not help but pull out my phone and investigate this orchestration of spontaneity. For better or worse, Situationist had already come and gone. It turns out that Apple banned the app due to unauthorized use of its location services. According to the app’s creators, this action was a “capitalist suppression of a post-Marxist subversive use of their fetishistic technology.” Even so, the buzz generated by the software remains, as demonstrated by its inclusion in MoMA’s recent exhibition Talk to Me: Design and the Communication between People and Objects.

I am thus left to my own devices when interacting with strangers. Happily. Truth be told, life is unpredictable enough these days as it is. Yet the novelty of the app inspired more serious inquiry into the historical aims of the Situationist International movement and how those ideas might be increasingly relevant in the context of modern day society and contemporary art practice. The ideal of constructing situations and creating experimental encounters is especially relevant to current art trends. While site-specific practice staked its claim as a serious player in the art world decades ago, there is an interesting shift with the proliferation of biennials happening around the globe and an increased sense of displacement for artists. Emphasis on experience as a state of flux is on the forefront for many negotiating the cultural realities of late capitalism. Considering the search for meaningful engagement in a society that feels increasingly fragmented, certain aspects of Situationist theory are more topical than ever.

Founded in 1957, the artistic and political movement known as the Situationist International (SI) developed to resist consumerist tendencies related to advanced capitalist society and the spectacle of mass media. Led by French intellectual Guy Debord and derived from art movements such as Dadaism and Surrealism, the Situationists distrusted the supposed successes of capitalism. Equating technological advancement and increased leisure with social alienation and growing dependence on commodities, their aim was to “counteract the spectacle.” By deliberately constructing situations that merged art and everyday life, they sought to reanimate life and revive the values of play and authentic desire over routine. These ideas would influence the student uprisings that took Paris by surprise in the spring of 1968.

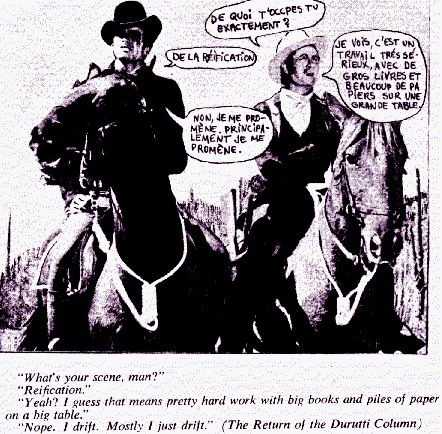

Though SI would officially disband five years after the uprising, the movement has since maintained a sort of cult following. Embracing concepts related to urban exploration, counter-cultural ideals, and a liberated sense of everyday life, punks and postmodernists alike continued to adapt these ideas to their own needs. I originally latched onto Situationist theory as part of the conceptual framework for some of my graduate work in Detroit. Assuming a quasi-ethnographic approach, I incorporated perimeters aligned with the core Situationist concept of the dérive. As Debord stated, “In a dérive one or more persons during a certain period drop their usual motives for movement and action, their relations, their work, and leisure activities, and let themselves be drawn to the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there.” I approached the work as a course of preparation and reconnaissance, a means of shaping my own brand of Situationist psychology in response to a city still coming to terms with its own history.

Art-world institutions’ evolving interest in site-oriented practice has stoked new discussion over the meaning of site, the physical mobilization of artists, and how work can effectively translate from transient experience to market value. In considering the shift from studio to situation, writer and curator Claire Doherty refers to context as “an impetus, hindrance, inspiration and research subject for the process of making art, whether specified by a curator or commissioner or proposed by the artist.” She goes on to discuss new exhibition models that address the implications of cross-cultural engagement and representation, citing the biennale as a natural home for situated practice. The very structure of these events is often geared towards transient encounters, responding to the atmospheric effects of the places they inhabit. In his 1957 report on the construction of situations, Debord advocated for a new architecture “based on the atmospheric effects of rooms, hallways, streets—atmospheres linked to the gestures they contain. Architecture must advance by taking emotionally moving situations, rather than emotionally moving forms, as the material it works with. And the experiments conducted with this material will lead to new, as yet unknown forms.”

Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller. “After Bahnof Video Walk,” 2012. 26 minute walk. Produced for dOCUMENTA (13), Kassel, Germany.

A compelling project with such aims took form last summer at dOCUMENTA 13 in Kassel, Germany (this event occurs once every five years; mark your calendars for summer 2017). Incorporating certain aspects of the dérive with the integration of modern technology, Canadian artists Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller created the work After Bahnhof Video Walk in response to their location in the old Hauptbahnhof train station. Using an iPod and headphones, visitors could walk through the station as the media played, featuring scenes accompanied by Cardiff’s gentle commands that guided them through the space. The resulting experience facilitated a powerful interplay between the real place and its mediated version, creating a mash-up of past and present, a situation both solitary and shared.

In another part of the station, Scottish artist Susan Philipsz installed an outdoor sound work that would provide an ethereal but intensely visceral link to the history of the site. By way of speakers installed above the train tracks, Philipsz projected a musical composition based on Czech composer Pavel Haas’ Study for Strings (1943). Composed while Haas was a prisoner at a concentration camp in the Czech Republic, the resulting orchestral arrangement would be used in a Nazi propaganda film produced before the composer’s subsequent transportation to Auschwitz. Learning the history of the Hauptbahnhof station as the site where Jews were deported from Kassel to concentration camps in 1942, the interplay of this composition with the ambient sounds of the trains created an experience that was as heartbreaking as it was beautiful.

In researching these site-oriented approaches, as well as navigating my own, I gravitate towards elements of both. There is the role of the artist as mediator: a purveyor of experience, engagement and creation of space for the unexpected. There is freedom as well as a gentle sort of mobilization in building a collective reaction to a space or situation. For artists like Philipsz, referencing the history of these spaces contributes to an evocative interpretation and deeper understanding of the site where it originated. In either case, this realm of contemporary practice begs an important question in terms of what it means to be “situated.” This is less about fixed location and more about setting the intentions of our work, determining how we want to intervene, collaborate or process. With an emphasis on experience as a state of flux, how does that affect our representation of time and understanding of history? In the creation of their video piece, Cardiff and Miller sought to “meld reality and fiction in an uncanny way,” creating confusion while also revealing the poignant moments of being alive and present.

In referencing these biennials and related events happening around the world, I admittedly veer from SI’s original focus on the experience of small-scale experimentation in everyday life. These events are assuredly a spectacle, though a different brand from those that the Situationists fought against. Reading about Sarah Sze’s upcoming installation in the U.S. Pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale, it is clear that transitory projects can operate on the grandest of scale. According to a recent press release from the Bronx Museum (selected as the commissioning institution for her works), Sze will create a sequence of constructed environments for the 55th Venice Biennale that will activate the Pavilion’s architecture and extend beyond the building and into the courtyard—blurring perceptual boundaries between the site’s interior and exterior.

Sarah Sze. “Strange Attractor,” 2000. Mixed media. Dimensions variable. Courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

In conjunction with the installation, the Bronx Museum also plans to launch an online component with streaming video documenting Sze’s process of conceiving, fabricating, and installing the piece. This will extend the project’s reach beyond the physical site to virtually link the artist with a worldwide audience. After his initial disdain, I think Guy Debord would have enjoyed watching Sze’s environment come to life. I’ve always thought of her installations and drawings as blueprints and models of cities as fascinating as they are illogical. They are a distant cousin, perhaps, of the psychogeographic maps cut up and reassembled by Situationists as they explored Paris in the 1960s.

Whether focused on small-scale experimentation or extensive movement, the subjective map is more relevant than ever. We can orchestrate experiences to heighten awareness of a location, blur spatial boundaries, and explore technology and time-based media as a means of expansion. As Debord stated, “the most pertinent revolutionary experiments in culture have sought to break the spectators’ psychological identification with the hero so as to draw them into activity by provoking their capacities to revolutionize their own lives.” Subvert, reassemble, build. Site may be an increasingly permeable notion, but one that remains compelling as ever in terms of navigation. In other words, time to get situated.