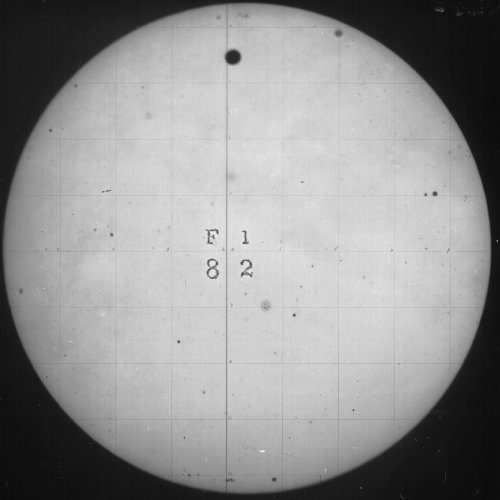

Image of the transit of Venus, 1882, taken by the Naval Observatory and Transit of Venus Commission. Dry collodion emulsion process. From the Naval Oceanography Portal, a website of the The United States Naval Observatory.

I am out to lunch with a good friend, talking about a new idea for a show. It’s a hot day (too hot), but I’m excited because I have the start of an idea: nothing mapped out, to be sure, but something. I want to restage an event that I read about recently, a 1958 event originally organized by the poet, ceramicist and former Black Mountain College professor M.C. Richards called Clay Things to Touch, to Plant in, to Hang up, to Cook in, to Look at, to Put Ashes in, to Wear and for Celebration.

I’m unable to articulate the specifics of how I would approach this new version of Clay Things, however, and the conversation hiccups and shifts course towards the trend in reinstalling older exhibitions, such as with 2011’s Photography into Sculpture at Cherry and Martin gallery here in Los Angeles. As enjoyable as that show was, why is it, my friend wonders, that art seems stuck in the past, without the same risk-taking that we see in the technology sector? I parry with a not particularly effective round of “what is art for,” but it’s a vapid effort, and with the heat and the rapidly nearing end of our lunch hour, the fight is lost before the real argument can even be defined.

Are we educated to favor innovation and foresight? Prometheus was the hero, not his brother, Epimetheus. “He who thinks before” brought us fire, capital, and the arts; Plato blamed the “scatter-brained” Epimetheus, or “he who thinks after,” for leaving humankind “naked and shoeless” and wrought with mischief. And whether he opened the box himself or not, it was Epimetheus who helped Pandora loose her plagues upon the world: “But he took the gift, and afterwards, when the evil thing was already his, he understood.” Yet the actions we take—the museums we build, the narratives we write, the longings we keep secret—belie the idea that Prometheus is our only role model.

It’s true that seeing ahead (or behind) is not a one-to-one replacement for that next step—thinking about what is seen—even if the actions often travel together. But there is something in a name, and Epimetheus’s gives a further clue: the Greek prefix “epi-” doesn’t mean “after,” but rather “upon, at, close upon, or on the occasion of.” Epimetheus does not so much represent the act of looking or thinking backwards, but rather that of acting on the wisdom of a conflated instant, when both present and past merge. “Hindsight” used to refer solely to that part of a rifle that was lined up with the foresight, which was then lined up with your target, a mechanical aid to help you extend your physical presence, to reach out and touch another and bring it to you, even in death.

Image of the transit of Venus, 1882, taken by the Naval Observatory and Transit of Venus Commission. Dry collodion emulsion process. From the Naval Oceanography Portal, a website of the The United States Naval Observatory.

Hindsight, then, is like an arrow, shot from our own time into another, but once something is speared, it has to exist in both times at once, pulled forward and reactivated. Walter Benjamin wrote, “It is not that what is past casts its light on what is present, or what is present its light on what is past; rather, an image is that wherein what has been comes together in a flash with the now to form a constellation.” Benjamin feared for those who suffered the illusion of historical progress, but have we moved too far in the opposite direction? Have we forgotten how to steal fire?

The march of time has not been kind to M.C. Richards. A friend and collaborator to artists like David Tudor and John Cage, she was a transgressive thinker in her own right, but she’s been mostly erased from the landscape of postwar American art. Clay Things, Jenni Sorkin now argues, is the second documented happening in contemporary art history, not Allan Kaprow’s 18 Happenings in 6 Parts—but do we live in a world where new constellations include stellar nurseries, or is our galaxy made up of dying stars?

Danielle Sommer is blogger-in-residence through May 29, 2013.