If it’s true that hindsight is more than an action we take from the present, but a conflation of present and past, a moment when time’s fabric bunches and we reach out and touch the object of our sights (pulling it forward), then, following in the vein of philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty, does this object touch us back?

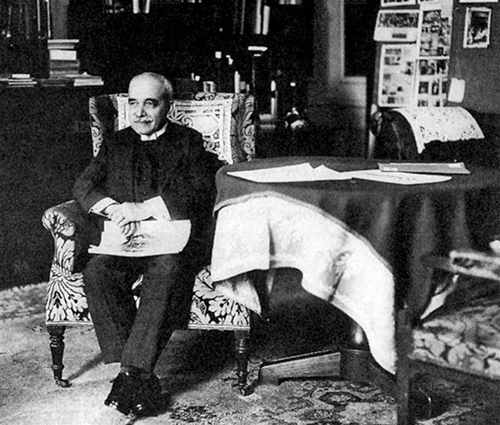

The pathos of the belief in this possibility can be found in the practice of German art historian Aby Warburg (1866–1929), particularly with his library and his final project, Der Bilderatlas Mnemosyne. As an eldest son, Warburg should have taken over the family banking business from his father, but on his thirteenth birthday, he allegedly offered this position to his youngest brother, Max, in exchange for the promise that Max would buy him all the books he ever wanted. Max kept his word.

By 1914, Warburg had amassed somewhere in the vicinity of 15,000 volumes, most of which were related to history, art, psychology, and religion. These volumes became the Kunstwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg—a research institute located in Hamburg that attracted scholars from all over Europe and America—and, eventually, the Warburg Institute, one of the more important art-historical think tanks of the century.

Warburg’s original cataloguing system, however, left many of the visitors to his library overwhelmed. He ordered everything according to what he called “the law of the good neighbor,” physically arranging (and rearranging) the books to critique, refute, or support each other. As a later scholar wrote, “A line of speculation opening in one volume was attested to or attacked, continued or contradicted, refined or refuted in its neighbor.”

Photograph of Panel 77 from Der Bilderatlas Mnemosyne, taken by Aby Warburg, 1925–1929. Photograph in the collection of the Warburg Institute, London

It was an extremely physical process; one that he repeated with the Mnemosyne picture atlas, which he worked on for the five-year period up until his death, juxtaposing images from different time periods against each other, hoping to understand why a particular style of representation or type of image would surface and resurface at different points in history, or in different cultures.

Der Bilderatlas Mnemosyne (named for the Greek goddess of memory) has enjoyed a second life over the last decade due to a renewed interest in archival projects, but what is fascinating about Der Bilderatlas is that, just like the library, it was frequently in motion. Warburg would order and reorder the images, as though to truly understand the links between past and present, he needed the physical experience, not just the intellectual.

Warburg manifested animist tendencies, and believed that the objects in his collections were charged with energy from a particular period. The photos included in Der Bilderatlas floated on large, black, rectangular panels that Warburg considered conductive. In the words of art historian Kurt Forster, for Warburg “to tap these batteries [artifacts] was to obtain a living current of life from the past.” He both touched and was touched.

Ultimately, Warburg’s system was too confusing for others. The library only really began to thrive after his family hired Fritz Saxl as an assistant, who created a workable catalog and began to manage its daily affairs. Warburg himself is rumored to have been schizophrenic, which would explain some of his behavior patterns, but for the sake of argument, it’s just as tempting to read the figure of Saxl as Prometheus and Warburg as a modern-day Epimetheus, “acting on the wisdom of a conflated instant.” In this version of the narrative, unfortunately, it is Epimetheus who is sacrificed, as though by opening himself up to the experience of being touched by the past, he is overrun.

Danielle Sommer is Blogger-in-Residence through May 29, 2013.